|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

“Lord, don’t shoot my boy!” screamed Beatrice Hamilton, 54, to the white man with the gun.

A second later, she heard a gunshot.

Her son, Rogers Hamilton, 18, shot in the head at close range, now lay in the dirt on the side of the road a short distance from where she lived.

The state of Alabama would do a brief investigation at the request of the Lowndes County Sheriff who did not arrest the white men who kidnapped and lynched Hamilton. The Lowndes County District Attorney never filed charges against anyone for the murder.

Lowndes County would come to be known as Bloody Lowndes because of all the violence perpetrated against the Black community by white supremacists, especially in the wake of the Brown v. Board decision in 1954, which required schools to desegregate.

The FBI would open the case for the first time in 2008 and closed it in 2016 after a scant investigation.

For almost 70 years, Rogers Hamilton’s murder — who killed him and why — has been the subject of speculation.

Through an analysis of news accounts, official government reports, and interviews with family members, Lowndes County residents, criminal justice experts, the motive for Rogers Hamilton’s murder and the men likely involved seem more evident now.

Shortly after the murder, the Black newspaper The St. Louis Argus reported that, “From Alabama this week comes a story that has all the earmarks of another Emmett Till case.”

Similar to the purported motive for J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant’s murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955 in Money, Mississippi, Rogers Hamilton crossed an invisible boundary. It was not a state law. It was a Jim Crow era social norm that would mark him for death by white supremacists.

He’d given a ring to a young Black woman. A white deputy sheriff was also interested in her. The pretext to kill him to get him out of the way? Waving at a white girl.

Rogers Hamilton: A favorite uncle

“He was my favorite, favorite uncle,” says Elizabeth Welch, 75, who grew up in the Hamilton household in a phone interview from her home in Cleveland.

Intersection McCurdy Road & State Highway 97, where Rogers Hamilton waved to the two teen girls.

Rogers Hamilton was the son of Beatrice and Henry Hamilton, a World War I veteran. They resided with their children, several grandchildren and extended family in a sharecropper’s home on McCurdy Road, a long stretch of dirt road off State Highway 97 in between Lowndesboro and Hayneville in Lowndes County, Alabama. Although Rogers Hamilton was among the youngest of their fourteen children, he was the oldest of the children living at their home at that time.

Rogers Hamilton’s aunt, Maggie Smith, 52, and uncle, Eli Smith, 64, lived nearby with their 16 children and extended family. Several other Black families lived on the McCurdys land and worked as sharecroppers on their dairy farm.

“My father died in 1955, so he was the man of the house and took care of everybody,” says his younger sister Beatrice Christian, 82, in an interview from her home in Cleveland.

Rogers Hamilton’s job was to milk cows early in the morning for the McCurdys, recalls his older sister, Jessie Lee Barber, 88, of Birmingham in an interview by phone in March, 2025.

“He was a good boy,” Barber said. “He didn’t bother anybody.”

According to a Jet magazine interview with Beatrice Hamilton, Rogers Hamilton was dating a young Black woman. He had given her a ring and planned to get married at Christmas.

The Pretext for Murder: A Wave

On Monday, October 21, 1957, Hulda Coleman, 17, drove west of Hayneville on State Highway 97. In the front passenger seat in her car was her close friend and classmate Carolyn Haigler, 17.

This was a regular after school activity for both white teens who were seniors in high school. They’d grown up together in Hayneville. Their grandmothers lived next door to each other and they were related by marriage.

As they approached McCurdy Road, Rogers Hamilton came into their view.

All three youths were around the same age, in high school in Hayneville and living in nearby communities.

However, they did not know each other. They attended segregated schools. At that time, Jim Crow segregation was the practice despite the 1954 US Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board.

Rogers Hamilton waved his arms as if he was attempting to flag down a ride home, roughly a mile away. He’d often caught rides from his employer George McCurdy, Jr., 36, and his employer’s wife Bettie McCurdy, 31.

Ms. Coleman did not stop the car or slow down to learn why Rogers Hamilton was trying to flag her down. She continued to drive at roughly the speed limit of 40 miles per hour.

Ms. Haigler didn’t think Rogers Hamilton’s wave was a problem.

However, Ms. Coleman seemed upset by the wave, says Carolyn (Haiger) Ikenberry, 84, (who later married and changed her last name to Ikenberry) in an interview at her home in North Carolina in February, 2025.

“She (Hulda Coleman) was shocked that a Black boy would wave at two white girls and try to stop us,” she said. “She wanted to go tell her father. I remember being really surprised that her reaction was so different from mine.”

At some point, before reaching Lowndesboro, Ms. Coleman turned the car around and started to drive back toward Hayneville.

Ms. Coleman dropped Ms. Haigler off at her house in Hayneville.

Encounter at Holliday’s Store

After dropping off her friend, Ms. Coleman stopped by Holladay’s Store, a local all-in-one grocery store, gas station and garage in Hayneville. She told at least one other person about the encounter, Bettie Wible, a former classmate and freshman at Auburn University.

Ms. Wible was leaving Holladay’s Store to walk over to see her mother, Olive Wible, 49, who worked as a social worker at the Pensions and Securities Office on the square in Hayneville.

“Hulda came up in a big hurry in her car, she drove in at an angle and jumped out of the car,” says Bette (Wible) Lewis, 85, (who later married and changed her last name to Lewis), at an interview at her home in Montgomery in March, 2025. “She was rattled. She was so upset about this Black boy who waved.”

Ms. Wible thought that Ms. Coleman was overreacting, and that a young Black man standing by the side of the road could not harm her driving in a car. She went home and told her family about the conversation.

Rogers Hamilton’s wave was a sign of familiarity to a white girl who did not know him. At that time, it could have been perceived as a threat, says Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Ohio State University professor and author of Bloody Lowndes: Civil Rights and Black Power in Alabama’s Black Belt.

In Lowndes County, a perceived threat, intended or not or by mistake, could have severe consequences. The county has had a “long history of violence to police the color line” and that was “rigidly enforced” especially if there was a threat to the status quo, he said.

Two White Men Kidnap, Lynch

“Rogers!” shouted a white man.

It was approximately 1:30 am on October 22, 1957, according to a U.S. DOJ report.

Two seconds later, the man shouted out Rogers Hamilton’s first name a second time, and then a third time.

He stood in front of Mrs. Hamilton’s residence next to the green truck. The other white man who drove stayed in the truck with the headlights on.

Having just awoken, Mrs. Hamilton thought the shout came from her employer, Mr. McCurdy. There would be no other purpose for someone else to be there. Their residence was off the main state highway with no close neighbors nearby.

McCurdy Road, where Rogers Hamilton was shot.

She woke up her son and told him to go outside to see what Mr. McCurdy needed, according to the statement she made later to investigators.

Rogers Hamilton was used to rising early before sunrise to milk the McCurdys’ cows, and may have thought he’d overslept and was late for that day’s milking, says Barber.

He got dressed so quickly that he left his shoes behind and walked out of the front door to talk to the man standing by the green truck. Mrs. Hamilton could not hear the conversation, according to an interview she gave to Jet magazine.

The man forced Hamilton into the truck and drove away from the family’s residence.

“My mom knew something was wrong,” says Roger Hamilton’s niece Elizabeth Welch. “She picked her coat off the rack and went running after the truck.”

“We told her not to go,” says Beatrice Christian, Rogers Hamilton’s older sister.

Mrs. Hamilton arrived at the scene in time to see one of the men holding a gun to Hamilton’s head.

“Don’t shoot my boy!” she shouted.

A shot rang out.

Rogers Hamilton fell to the ground.

The two men got into their truck and drove away on the dirt road towards State Highway 97.

Mrs. Hamilton leaned over her son with her flashlight. She later told reporters at Jet magazine that she saw him breathe his last breath.

Seeing that he was shot in the forehead, she ran to her sister-in-law, Maggie Smith’s house to alert her relatives. Then she ran to the McCurdy plantation house to ask Mr. McCurdy to telephone Sheriff Frank Ryals, 52, to request help.

Several other white men – believed to be klansmen – encircled the house.

They were looking for two other Hamiltons, cousins Henry and Preston, recalls Welch.

“Klansmen were running to windows and looking in and hollering,” she said. “Everybody was scared.”

When Mrs. Hamilton returned to the house with Maggie Smith and her husband, Eli Smith, the klansmen scattered. The Smiths took all the Hamilton children to their house for the next few nights.

An ambulance arrived some time later. Hamilton was pronounced dead.

The State investigates

Later that same morning, Sheriff Ryals called the Alabama Department of Public Safety (DPS) to request that the state investigate Rogers Hamilton’s death.

Although it was not standard procedure to ask the state to investigate, the sheriff may have believed members of his department were involved. He asked the state to investigate to avoid any appearance of a conflict of interest or to keep himself out of any involvement.

A few hours later, DPS investigator Oscar K. Corley, 63, arrived in Lowndes County from Mobile.

Corley stopped by the Lowndes County sheriff’s office, located at the county seat in Hayneville, and invited a second investigator, Deputy Sheriff Joe Jackson, to join him.

That may have been to help Corley make his way around the county since he did not know the area.

However, that action – intentional or not – worked at cross purposes with conducting an independent investigation.

Corley, along with Jackson, interviewed a handful of people that afternoon, starting with Mr. McCurdy. Corley interviewed a Hamilton family member who was in the house at the time. He also spoke with two African American girls who knew Rogers Hamilton.

Then he interviewed Mrs. Hamilton. She recounted the details of the murder, stating that two white men were involved.

However, she did not name any suspects.

After interviewing a handful of people, Corley wrote up his report stating that he believed that Mrs. Hamilton could not have seen the men who took away and shot her son. He wrote that she was confused about what occurred, according to a U.S. Department of Justice Notice to Close memo.

That same day, Hamilton cousins Preston and Henry left town to avoid a similar fate as Rogers Hamilton from the klansmen who’d called for them in the wee hours of that morning.

Same color, wrong car

Later that day, Olive Wible came home for lunch from her job as a social worker handling welfare cases and shared her conversation at work earlier that morning, recalls Bette (Wible) Lewis.

Mrs. Wible told her daughter what had been shared with her by Bettie McCurdy, the employer of the Hamilton’s who also happened to be Mrs. Wible’s secretary at the Pension and Securities office. Mrs. McCurdy said that some men had killed Rogers Hamilton the night before. She was distraught about the murder.

Mrs. Wible responded by telling Mrs. McCurdy about Rogers Hamilton’s wave, and together they realized what likely happened.

They determined that the Coleman and McCurdy cars were the same color.

That meant that from a distance, Rogers Hamilton may have thought he was flagging down Mrs. McCurdy especially as she frequently gave rides to the Hamilton children.

Mrs. Wible and Mrs. McCurdy made these connections, but no state, local or federal investigators would ever ask them about it.

Family buries Hamilton, leaves Alabama

“My daddy was real upset,” recalled George “Mac” McCurdy III, 78, about Rogers Hamilton’s death, in an interview outside his home in March, 2025.

On October 24, Sheriff Ryals signed Rogers Hamilton’s death certificate which lists his death as a homicide and the cause of death as a gunshot by “person or persons unknown.”

The death certificate indicates that no autopsy was performed.

The following Saturday, five days after Rogers Hamilton’s death, Mrs. Hamilton and her family held a funeral service at the Baptist Hill Church on State Highway 97. Reverend O.T. Harvey presided over the service.

The family arranged for the burial in the Haynesville cemetery where Rogers Hamilton’s father, Henry Hamilton, was buried two years before in the cemetery’s Black section.

However, when the family arrived at the cemetery entrance, members of the sheriff’s department and townspeople barred them from entering, recalls Roger Hamilton’s niece Elizabeth Welch.

“I’ve never seen my grandmother cry so much when they turned us away at the cemetery,” she said.

The family left and took Rogers Hamilton to another cemetery, the Baptist Hill Memorial Cemetery Pine Grove Annex, on Route 80 near the intersection of Route 97. They buried him in an unmarked grave.

After the funeral, Mr. McCurdy went to see Mrs. Hamilton.

He told her that he could not keep her family safe, according to family members.

To help her move her family, Mrs. Hamilton called some of her older children who lived outside Lowndes County in Birmingham, Cleveland, Chicago and New York.

They left, never returning to live in Lowndes County.

The other families sharecropping on the McCurdy land left soon after.

With no sharecroppers to work at his dairy farm, McCurdy’s dairy closed, according to Willie Davis, 83, a Hayneville resident who’d hauled hay for the McCurdys.

Mother says deputy sheriff pulled the trigger

While Mrs. Hamilton did not disclose to state and local investigators who she saw that night shoot her son, she did tell her family. One of the men she saw that night was Deputy Sheriff Luck Jackson. He also worked by pumping gas at Holliday’s store in Hayneville.

She also recognized Jackson’s voice as the man calling out for her son.

That explains why she did not name anyone to investigators. Deputy Sheriff Joe Jackson who had accompanied Corley on the state investigation, was also the brother of Deputy Sheriff Luck Jackson, one of the men she saw kill her son and.

That also explains why she changed her story. At first she said the men were white. Then she said the men were Black. If she’d identified a deputy sheriff as the subject of a murder investigation, she or her family members could have been targeted for death.

She never mentioned the klansmen at the house to investigators.

In not telling investigators who killed her son, Mrs. Hamilton “protected not only herself but others who may be subject to violence, even death,” says Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries. “She’s well aware that these people won’t be brought to justice.”

“She likely made the decision to leave Alabama out of fear and concern for the safety of her family. The fear would have been that those who murdered her son would do harm to her and or her family to keep them quiet, to keep them from pursuing justice,” he said.

Several weeks after Rogers Hamilton’s burial and his family’s departure from Alabama, The Pittsburgh Courier ran a story on November 9, 1957 that gave several possible motives and named at least one man who may have been involved in the murder.

The article stated that Hamilton and Deputy Sheriff Luck Jackson were interested in the same young Black woman.

Mrs. Hamilton told her children that this was the real reason her son was killed.

“After he gave a ring to the young woman, the (deputy) sheriff found out and got really mad,” says Rogers Hamilton’s niece Elizabeth Welch.

A suspected klansman involved

The second motive mentioned in the Pittsburgh Courier story stated that Hamilton may have waved at a white teen. She came back later with some men to warn Hamilton with a beating a few days before the murder.

That second possible motive hadn’t been examined until recently when veteran journalist John Fleming published a new story about the case, following his three-part series in 2010 that comprehensively covered the case in The Anniston Star.

Thomas Lemuel Coleman, Sr., 46, has emerged as one of the possible men involved because his only daughter, Hulda Coleman told two friends that she intended to tell her father about Rogers Hamilton’s wave which happened to be the day before his murder.

However, Mrs. Hamilton did not share with her children who the second man was who drove the truck.

Her mother did not know who Thomas L. Coleman, Sr. was, says Rogers Hamilton’s older sister Beatrice Christian.

The investigation lags

The local press did not report on Rogers Hamilton’s murder.

One news outlet, The Montgomery Advertiser, in the adjacent county, published an article on November 13, 1957 in response to Sheriff Ryals’ complaints about press reports from newspapers, such as The Pittsburgh Courier, that alleged Hamilton’s death was a lynching.

“Our investigation has revealed nothing that leads us to believe these reports,” he said.

The Montgomery Advertiser also reported that Ryals said Rogers Hamilton’s death was “caused by a slug from a pistol of undetermined caliber fired at close range.”

A few weeks later when Bette (Wible) Lewis was at home in Hayneville over the Thanksgiving holiday, she saw her dad, James Wible, 45, who was elected mayor Hayneville. He was with Larue Haigler, 54, who was later elected to the Hayneville council.

She asked them what was being done about Roger Hamilton’s murder.

Mr. Haigler told her that the murder was being investigated.

However, state investigators never explored further either possible motive or the possibility that the motives were related.

Investigators did not examine the most plausible scenario. The men involved used Rogers Hamilton’s wave as the pretext to kill him. He would no longer be an obstacle to the deputy sheriff’s pursuit of a love interest.

Sheriff Ryals and his successors did not take any additional investigative actions after Corley’s preliminary investigation on the day of the murder. Nor did they ever arrest or charge anyone for Rogers Hamilton’s murder.

The Lowndes County District Attorney’s Office never charged anyone with any crime in this case.

Eight years after Rogers Hamilton’s death, all of Lowndes County and many people across the country would come to know Thomas L. Coleman, Sr. He was prosecuted and acquitted for another murder in a highly publicized trial in Hayneville for shooting and killing Jonathan Daniels, a civil rights worker and Episcopal seminarian.

How an all-white jury’s acquittal sparked legal reform in Alabama

Thomas L. Coleman, Sr. died in 1977. His family buried him in the white section in Hayneville Cemetery.

At an interview on his front porch in March, 2025, Thomas Coleman, Jr., 85, did not recall his father mentioning any involvement in Rogers Hamilton’s murder, or his sister ever telling him about her encounter with him.

Decades later, the FBI opens, closes the case

On October 7, 2008, President George W. Bush signed the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Act (P.L. 110-344) into law to investigate civil rights crimes that resulted in a death before December 31, 1969.

Based on input from FBI field offices and national civil rights organizations, Rogers Hamilton’s name was on the list that the FBI created of civil rights era unsolved murder cases.

In opening Rogers Hamilton’s case for the first time, even though the FBI was aware of the murder in 1957, the FBI conducted a review of the records and newspaper articles, according to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Notice to Close memo.

The FBI looked for Sheriff Ryals, DPS Investigator Oscar Corley and Mrs. Hamilton.

While finding deceased individuals that appeared to be Sheriff Ryals and Corley, the memo says that, “no identifying information was located during the search that would positively identify Beatrice Hamilton.”

It appears that the FBI did little else beyond the records search.

Despite the fact that Corley’s investigation included an interview with an individual whose name is redacted – a Hamilton family member who was inside the house at the time of the murder – the U.S. DOJ Notice to Close memo did not indicate that the FBI searched for other Hamilton family members.

The FBI did not conduct an in-person investigation in Lowndes County, nor did they draw leads from John Fleming’s 2010 news articles where he extensively reported on conversations with residents of Lowndes County.

The U.S. DOJ Notice to Close memo does not mention the FBI’s own report from 1957 that outlined possible motives and contained information that Sheriff Ryals advised the FBI about Rogers Hamilton’s wave.

The DOJ memo concludes that the “victims’ death was investigated locally, but the subjects were never identified, nor were the investigators able to determine the motive for the killing.”

In closing the case on February 10, 2016, the U.S. DOJ Notice to Close memo concluded that, “Due to the lack of identifiable subjects and the destruction of the Lowndes County Sheriff’s Office reports and records, a successful prosecution of this case would be highly unlikely.”

Too late for justice, Rogers Hamilton is remembered, honored

There was no justice at all in her brother’s case, says Rogers Hamilton’s older sister Beatrice Christian.

“It’s too late for that,” says Christian for the state of Alabama or Lowndes County to do anything now for their family’s loss.

There is no visible remembrance in the area where he was murdered.

In December, 2024, the editorial board of the local newspaper in the area, The Lowndes Signal stated that the county has 24 historical markers, several of which are in civil rights cases. An historical marker remembering Rogers Hamilton cannot be found among these 24 historical markers.

However, Rogers Hamilton is remembered.

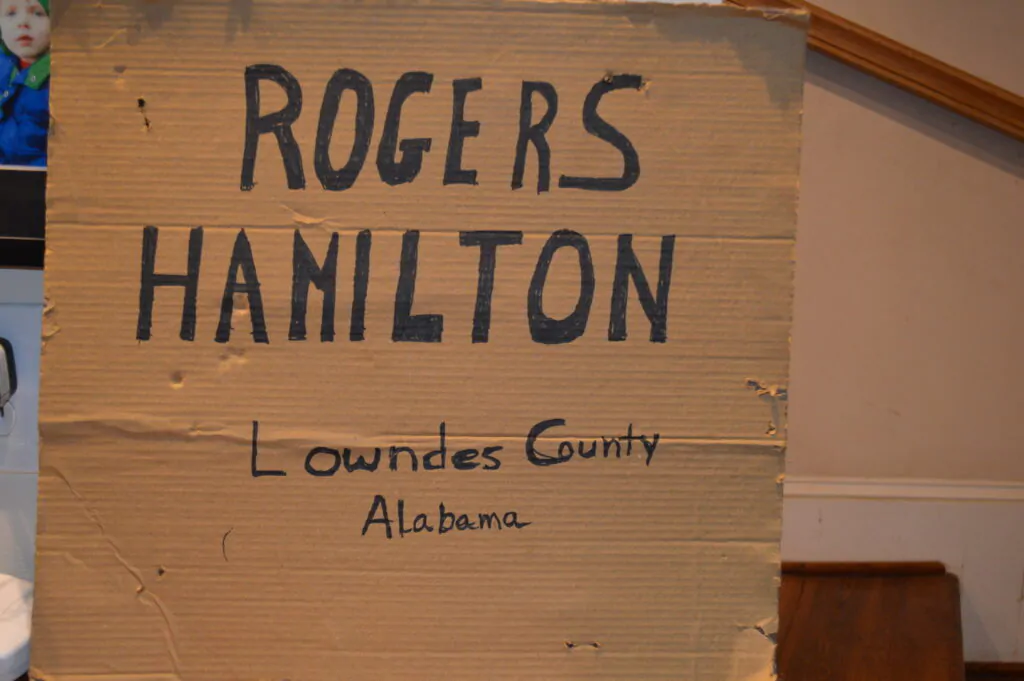

A Rogers Hamilton sign.

“It is evil what happened to him,” says Carolyn (Haigler) Ikenberry who made a sign with Rogers Hamilton’s name and took it to several Black Lives Matter demonstrations where she lives in North Carolina.

In Montgomery, Hamilton is honored on several monuments.

Hamilton’s name is identified on the Southern Poverty Law Center’s (SPLC) display, Wall of the Forgotten, in Montgomery, Alabama with 73 other individuals. SPLC states that these are individuals “who died between 1952 and 1968 under circumstances suggesting they were the victims of racially motivated violence.”

Equal Justice Initiative’s Peace and Justice Memorial in Montgomery, Alabama unveiled a new monument in 2019 honoring Rogers Hamilton, along with 23 other individuals who were victims of lynchings.

“The more we make the public aware, the less likely that lynchings will occur,” says Josephine Bolling McCall whose father, Elmore Bolling, was lynched in Lowndes County in 1947. Bolling McCall has led efforts to raise awareness about lynchings in Alabama.

“The definition of lynchings does not include the type of murder, but the number of persons who commit the crime and there’s no due process,” says Bolling McCall.

“My father was shot six times with a pistol and once in the back with a shotgun,” she said.

In 2022, a bus load of Hamilton family members, including Beatrice Christian, as well as a bus with family members from Chicago drove to Alabama for a family reunion. Wearing royal blue tee shirts with Hamilton Reunion written on it, they traveled to Montgomery to see Rogers Hamilton’s name etched on the side of the memorial.

Four sisters of the 14 Hamilton siblings were alive to witness the monument.

“I loved my brother,” says his younger sister, Jessie Lee Barber. “I miss him.”