It took 10 years for John Woods to even get a chance at parole inside Alabama’s prison system, something he worked for inside with the hopes of being released. But like so many incarcerated men, Woods was denied parole, multiple times, and began to lose hope.

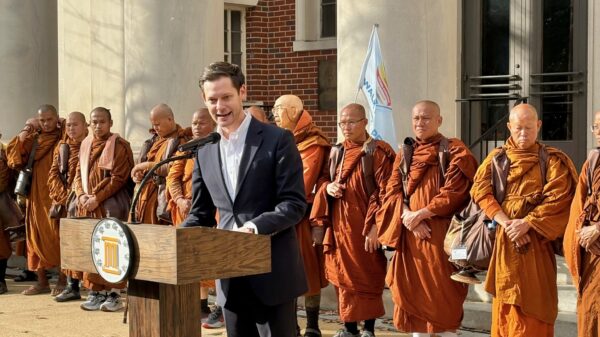

Woods joined a panel of experts Monday brought together by Alabama Values to discuss the Alabama parole system and its flaws and failures.

Paroles in Alabama have been few and far between since 2019, after Jimmy O’Neal Spencer murdered three people while out on parole. The public backlash led lawmakers to overhaul the parole system. But the changes made wouldn’t have even made a difference in Spencer’s release, said Katie Glenn of Southern Poverty Law Center, and have created an oppressive system for incarcerated individuals.

“That’s the way we legislate in this state; we’re reactionary,” Glenn said.

“But we’re only reactive in one way: punitive,” added Alison Mollman, legal director for the ACLU of Alabama. “We are not reactive to the trauma we are seeing inside the prison system.”

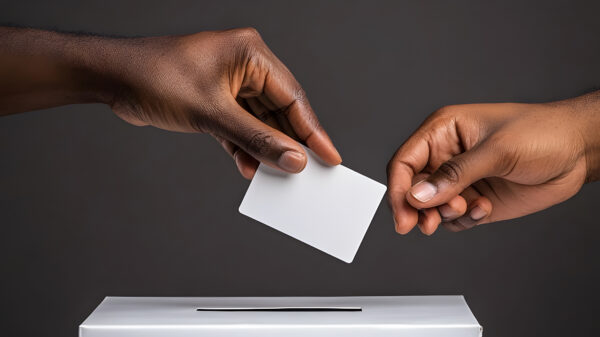

Since 2019, parole approval rates have plummeted from more than half of applicants being released to lows of 1 to 3 percent per month. Those numbers have recently risen slightly back to about 20 percent of applicants being granted parole.

Guidelines created by the parole board consistently show upwards of 75 percent of applicants should be released by the board’s own standards.

Pat Vandermeer of Alabama CURE said the presumption of denial among Alabama inmates leads to a pervasive hopelessness within prison walls. Incarcerated men are less likely to participate in programs, obtain their GED or learn new skills since the involvement in the programs has done little to help them leave prison early.

Mollman said there are three attainable goals that could helot improve the parole situation.

First is to allow parole applicants to virtually attend their own hearings. Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, has brought forward legislation to that effect in previous sessions.

“We have the technology to do it,” Mollman said. “People deserve that opportunity.”

Parole applicants currently have no chance to plead with the parole board, while families of the victim and representatives of the attorney generals office and VOCAL Alabama are often present to oppose release.

Another improvement, Mollman said, would be to limit the amount of time parole can be set off. When an applicant for parole is denied today’s he parole board can set the next parole hearing off for up to five years, and does so in most cases. Other states have more immediate opportunities for another chance at parole, Mollman said.

In Iowa, parole applicants have a hearing annually and the system works to gradually release inmates back into society with a staggered release. The first level is work release, with the incarcerated individual being required to return to jail at night; the second level is release to a reentry home and then again for full parole.

“By the time they are fully granted parole, many of them hav drivers licenses and their own apartments, because the system is prioritizing rehabilitation rather than punishment,” Mollman said.

Third, Mollman said Alabama should look into some kind of “restorative justice” model that allows the family of victims to voluntarily interact with the perpetrator of the crime, as it has shown in other states t provide potential pathways for healing and forgiveness.

Glenn said it sometimes feels like it’s one step forward, two steps back with the Legislature, as high profile events shape the way lawmakers think about the system. However, there has been some hope recently, Glenn said, in part due to two meetings of the Joint Prison Oversight committee where mothers of incarcerated men shared their stories and pleaded to lawmakers for help.

“That was the most heart-wrenching meeting I’ve ever sat through,” Glenn said. “It was clear that meeting affected some of those legislators on that panel.”

The second meeting brought about a dozen lawmakers who don’t serve on the committee to listen in, Glenn said, showing the interest that the first meeting had spawned.

The Alabama Legislature will have a new opportunity to wrestle with the Alabama parole board when it meets for its 2025 legislative session in February.