Saturday morning, the sports world was up in arms.

Kirk Herbstreit, a longtime ESPN analyst and College Gameday regular, had gone on a rant during that morning’s show – picking up from comments made by former Alabama head coach Nick Saban – essentially saying that Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) payments to players, along with the transfer portal, were giving players all the power and hurting the game.

Herbstreit’s comments – and the sentiments from Saban and others concerning NIL and the portal – were prompted by the story of Matthew Sluka, the QB for undefeated UNLV who earlier in the week walked away from the team after it failed to deliver on promised payments of $100,000.

The outrage and disbelief on the set – and around the college football world as a whole – was comical.

Listening to these guys, it was as if the college football world was on the verge of implosion. It was unsustainable, they said. It was catastrophic for “the game,” they said.

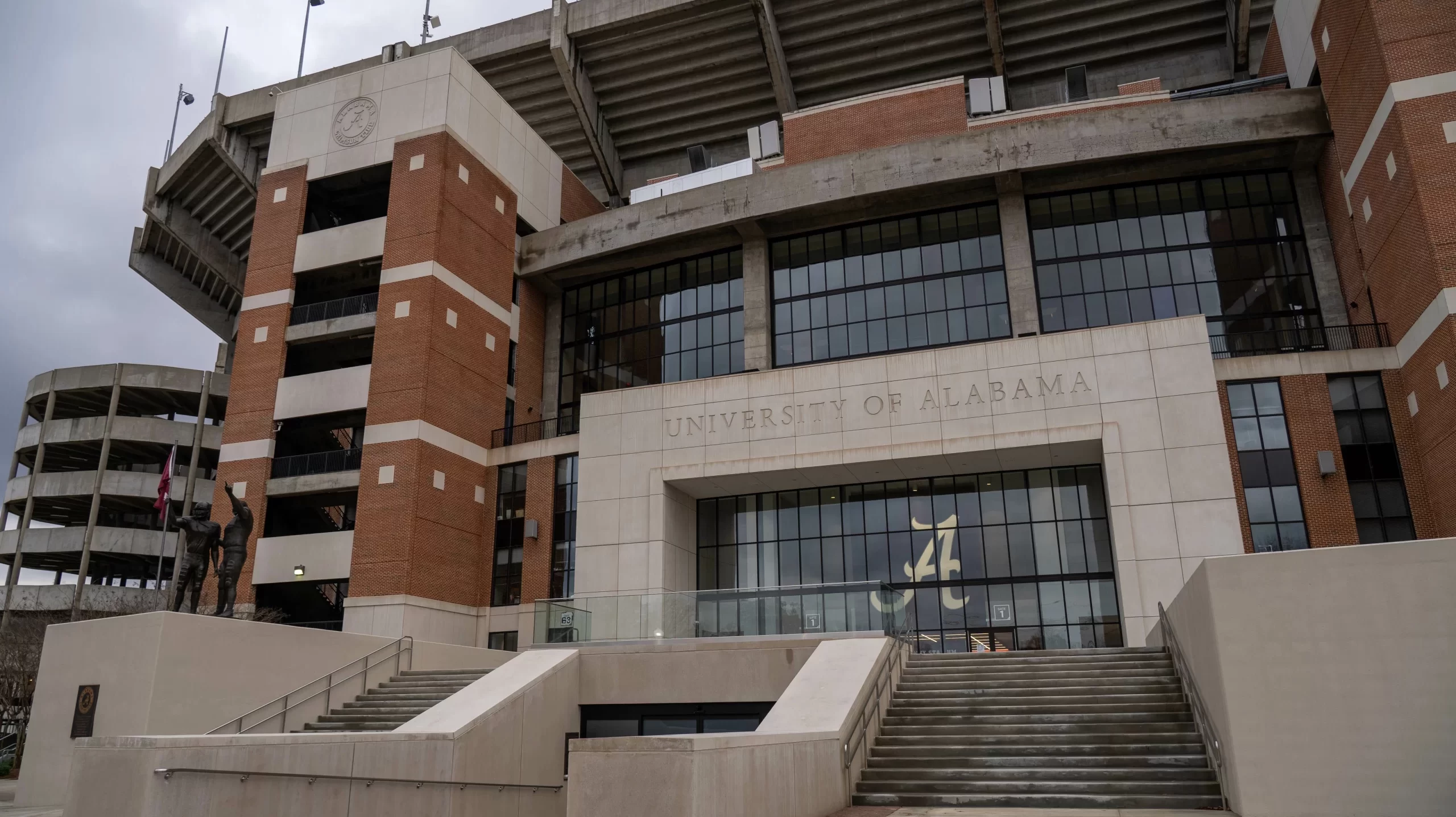

About 12 hours later, after a day of fantastic games and a Georgia-Bama matchup that was one of the best regular season football games in history, “the game” seemed as if it was doing just fine.

I know, I know – this is a political website where you expect to receive a daily dose of political news and you look elsewhere for sports content. I agree with you. But this happens to be one of those stories that bridges the gap between sports and politics.

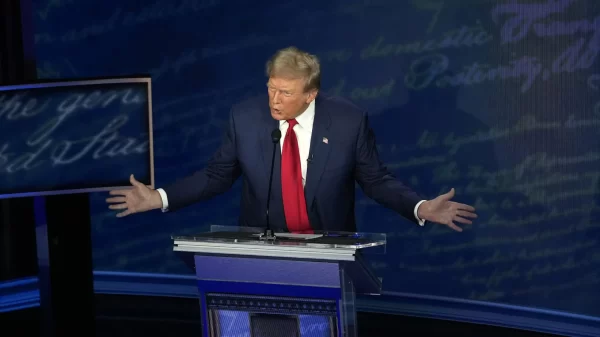

Currently, college figures, including Saban, are asking Congress – which includes geniuses like Tommy Tuberville – to intervene in college athletics and pass legislation that “fixes” NIL payments. They want to curtail the payments going from college collectives to players, who are making upwards of $1 million a year in some cases, and instead implement a more controlled, and controllable, system of payments.

Tuberville, of course, is all on board and has been lecturing everyone on the damage this new system is bringing about.

It’s BS.

The simple fact is this: For decades and decades, the people who are now crying because players have “too much control” are the same ones who raked in cash hand over fist from exploiting, mistreating and controlling a forced-ameteur workplace in which the employees responsible for BILLIONS in annual revenue weren’t allowed to profit.

When the players tried to unionize, these same people fought it.

When some advocates tried to implement safeguards and protections for players, they fought it.

When kids had their entire lives upended and were painted as cheats because they accepted a few hundred bucks to keep their mom’s lights turned on, no one raised a finger to challenge the system as it was.

Not a single lawmaker stood up for anyone. But now, a guy who once worked as a college coach and who bounced from job to job so much that he once left recruits at a dinner to go take another job is going to lecture everyone on the virtues of honoring commitments and not allowing personal greed to tarnish the game? Please. I’d rather listen to that guy try to name the three branches of government. Again.

Here’s the dirty little secret: College coaches are fighting against the NIL system in its current form because it has the potential to significantly reduce their salaries.

In case you’re unaware of how the college athletics funding works in the world of big-time football (and basketball at some schools), let me provide a bare bones breakdown: The schools themselves only pay a tiny fraction of the extra large salaries doled out to coaches. Of Saban’s roughly $10 million per year salary, the University of Alabama was only paying a couple hundred thousand.

The rest is picked up by a fund – they all have university-specific nicknames – that is supported by major boosters, who donate millions of dollars every year to see their favorite college football team (hopefully) perform well.

But now, in the new world of NIL – which came about after a couple of federal court decisions finding that players had been exploited for years – those same boosters are donating funds to collectives that support paying recruits and transfers to attend their favorite universities.

So, if Joey Booster is dumping cash into the NIL collective at his favorite college, instead of supporting the fund that goes towards paying the exorbitant coaches’ salaries, guess who’s about to take a pay cut?

And they should.

There’s a reason college coaches are in some cases making more than NFL coaches – they’ve been working in a market where there’s no labor costs. Because it was artificially capped by a now-illegal determination that amateurism could be used as a means to deny proper salaries.

The NCAA, and all of these coaches and college administrators, could have avoided this scenario at any point over the last several decades had they taken any step whatsoever to treat players fairly. But instead, they decided to continue raking in as much money as possible off the backs of these guys while steadfastly fighting any effort to ensure fairness.

How bad was it?

As these people are whining about the transfer portal, someone should let everyone know that those football scholarships have always only been for a single year and have to be renewed each year. What has changed is that the NCAA can no longer impose a one-year ban on participation for any athlete that transfers and coaches can no longer block players from transferring to certain schools.

Think about the hypocrisy required from a bunch of dudes who routinely bounce from job to job who are now whining because they can’t block a player from transferring to a different school. The entitlement is insane.

And really, that’s all any of this is about – the entitlement of people who have reaped the unfathomable rewards of a rigged system trying to convince everyone that there was some sort of honor in the way it used to be.

The reality is what we all saw late Saturday night. College football players are making a little money. Viewership is still off the charts. There’s more money than ever. The players have the control they’ve always deserved.

The free market is working and working well within college football right now. And the last thing the sport needs is government intervention to stop it.