A thoughtful conversation took place Wednesday at the Alabama State House.

I will pause here for you to remove your jaw from the floor and gather yourself.

Because it’s true. A thoughtful, deliberate, compassionate conversation between Republicans and Democrats over the rights of – and seriously, you should hold onto your jaw again here – incarcerated individuals.

You could have knocked me over with a feather.

But for a solid 20 minutes, lawmakers on the House Judiciary Committee debated earnestly a bill sponsored by Sen. Will Barfoot to provide incarcerated people who are up for parole an opportunity to be present, via telephone or video conference, their parole hearings.

To be clear, no one on the committee was arguing against allowing the telephone/video conferencing. Instead, the debate occurred when Rep. David Faulkner introduced a substitute version of the bill that switched up the start dates should the bill pass. Instead of requiring that inmates be allowed to participate by video conferencing in Oct. 2024, Faulkner’s bill would allow telephonic participation by that date and video conferencing by Oct. 2025.

It also made one other change: It changed the language from “an incarcerated person shall be allowed …,” to “an incarcerated person may be allowed ….”

Rep. Matt Simpson had a problem with that.

“If you make it where that isn’t required, they’re not going to do it,” Simpson said. “If you say you may do something, they can read it as you may not do it and there’s nothing to make them. It won’t work.”

He’s right, of course. Alabama’s Pardons and Paroles Board doesn’t do half the things it’s required to do under the law now, particularly when it comes to honoring the rights of incarcerated people. You give them an option, we know what option they’re going to choose.

Faulkner said his intent with changing the wording was to cover the state in the event of technical difficulties. Basically, if the phone or video system screws up, the board won’t be required to reschedule or delay a hearing.

“If you make it ‘shall,’ then that creates a right,” Faulkner argued. “If you go from ‘shall’ to ‘may,’ you don’t have any right to waive.”

To which several of Faulkner’s colleagues said, Um, yeah, that’s the point, man.

“There’s just a fundamental right for a person to be present and have their voice be heard on something that involves their life,” Simpson said. “There’s a right for people to be present at their own court proceedings.”

And the hits kept coming. Rep. Jim Hill, a former circuit court judge, said he couldn’t get behind any language that didn’t require that the subject of the parole hearing be present.

“Mr. Faulkner, I’m going to be honest with you, I don’t see any reason that an individual who is before the parole board should be allowed to have whatever say he wants to have as long as it does not impact or come in contact with the victim or victim’s family,” Hill said. Barfoot’s bill prohibits the incarcerated person from seeing or being seen by or communicating with the victim or victim’s family.

“If you make it may, in all likelihood they won’t be there, and no, I can’t go along with that,” Hill said.

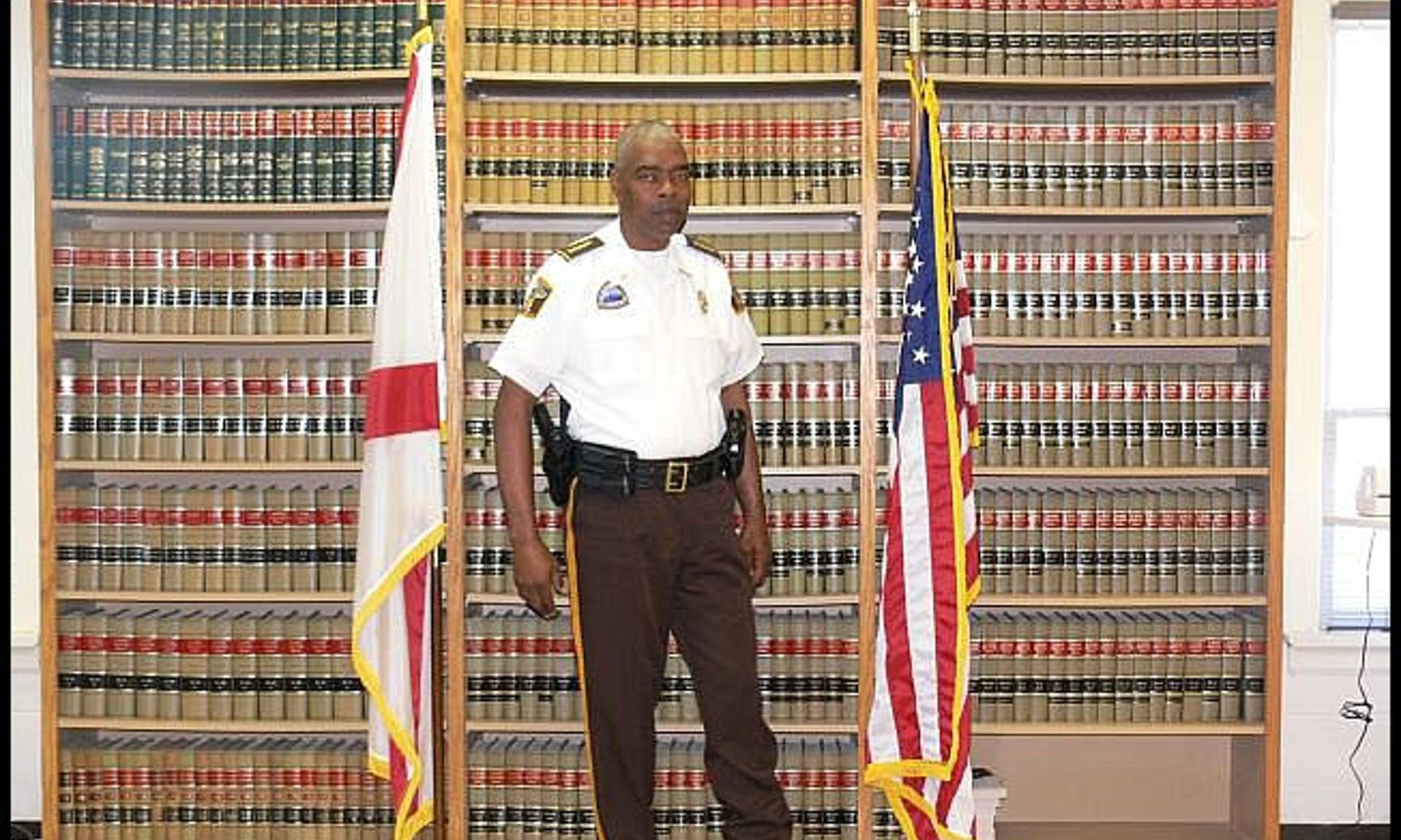

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out that there was one small dip into the ignorance pond, when Rep. Russell Bedsole decided to grandstand for a moment. Lost in the momentum of his own words, as he argued against giving incarcerated people the right to be heard at parole hearings, because “parole is privilege and not a right,” Bedsole appeared to briefly argue that there shouldn’t even be parole because “the person had their day in court.”

But Bedsole, a former law enforcement officer and jail administrator, also wanted everyone to know that he’s “all for the equal treatment of people.” But also maybe we shouldn’t give these incarcerated people an opportunity to go before the parole board, because during that hearing the person will be on their best behavior and will probably act differently outside of that hearing.

No, for real. He said that. And used this example to support that nonsense.

“In my role as a jail administrator, I had to serve as an appeal process,” he said. Bedsole went on to describe a scene in which inmates came to him to appeal punishments, and “they would be on their absolute best behavior.” But later, those same inmates, he learned through recordings, would say things that were “less than perfect.”

Anyway, Simpson squashed that nonsense in about 12 seconds, simply by pointing out that no one was saying that parole was a right, but that participating in governmental hearings in which your life and actions are being discussed should be considered a right.

Back on track, Rep. Chris England, the ranking Democrat on the committee, pointed out that the presence of the incarcerated individual during the hearing could only serve as a means to provide the board with more information. The inmate could offer explanations, answer questions or correct errors. All of it making the board more informed.

Rep. Shane Stringer, a former police chief, argued that incarcerated people are allowed a process now in which they present their case to an officer, gather letters of support from guards and others and all of it is given to the parole board. He didn’t see the need for them to go before the board.

Ultimately, Hill, the chairman of the committee, decided to delay a vote on the bill until Thursday morning, giving members an opportunity to read through the substitute version submitted by Faulkner. But as he did so, he pointed out that as a judge for more than 20 years, he revoked a lot people’s parole, but said he never did so “without looking them in the eye.”

That’s important.

It would probably also prevent the board from denying parole to dead people.