|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

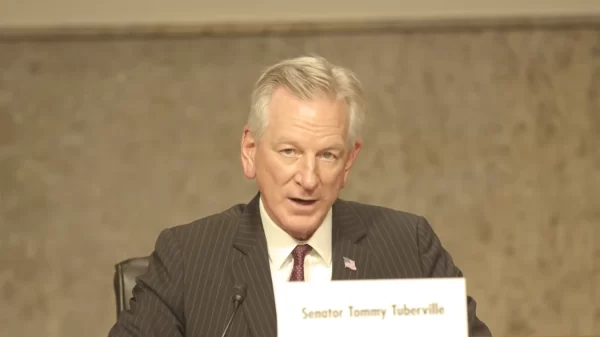

The email landed in the inboxes of at least a half-dozen Alabama senators a few days ago – it purported to warn them of “hidden” items buried sneakily within a gambling bill passed by the senate two weeks ago. Apparently written by a former Alabama supreme court justice (or at least bearing his name), the email, naturally, got some attention.

But that email, which is filled with inaccuracies, hyperbole and leaps in logic so great that it’s genuinely hard to believe any attorney, much less a former justice, could get the law so wrong, is a case study in all that is wrong with Alabama’s current state of gambling.

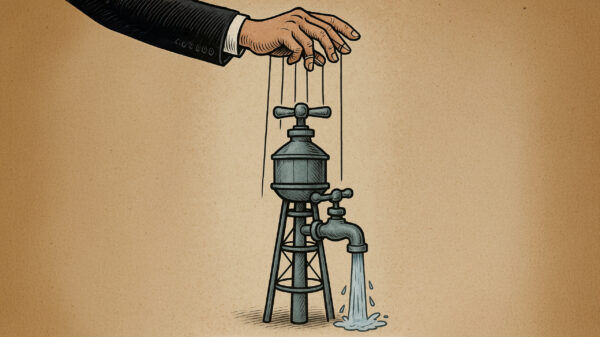

In fact, if you’ve ever wondered how the state got in this mess, this email is how: powerful people using their influence and positions to push an agenda – whether one based in personal beliefs or influenced by money – and relying on the complicated nature of state and federal gaming laws to confuse the situation enough to maintain the status quo. Because the status quo is keeping a lot of people rolling in cash.

It’s unclear the motivations of former justice Glenn Murdock, the apparent author of the email. Murdock seems to be employed in some capacity by anti-gambling groups, including the Alabama Policy Institute and the Southeast Law Institute – a group headed by far-right attorney Eric Johnston, who has had his hand in everything from anti-gambling efforts to Alabama’s draconian abortion laws.

But Murdock also has a long and sordid history in Alabama’s gambling fight – one that has routinely pitted him against the Poarch Band of Creek Indians and against traditional casino owners. He was the author of Alabama’s controversial and unique opinion that limited bingo games in the state to paper-only – a requirement not honored by any other state or the federal government.

That ruling boosted the efforts of former Alabama Gov. Bob Riley, who became oddly fixated on stopping gambling expansion in the state. There were numerous reports later that during that time Riley was being influenced by casino money flowing from the Choctaw tribe, which operated casinos in Mississippi and didn’t want the Alabama competition. A U.S. Senate investigation that resulted later in the conviction of lobbyist Jack Abramoff offered some details of the cash that went to Riley.

I attempted to reach Murdock to ask about his claims and why he would make them, but he didn’t answer and didn’t return the message I left on his cell phone. So, it’ll be up to you to decide.

In his email, Murdock essentially makes two major claims: 1. That the gambling legislation recently passed by the Alabama Senate, which stripped down a bill passed by the Alabama House to only a lottery, historical horse racing games at state dog tracks and a potential compact with the Poarch Creeks for casino gaming, would in fact allow for much wider expansion, including into Baldwin County, Huntsville and downtown Birmingham; and 2. That sports wagering allowed on tribal lands under a compact with the Poarch Creeks would allow for internet gaming statewide.

Let’s take the simplest first.

Whether sports wagering would be available off of tribal lands, including through online apps, would be determined by the specifics of the compact negotiated by the governor and tribal leaders, and later approved by the federal government. It really is that simple.

(And just FYI: Murdock’s email makes it seem as if the Poarch Creeks are trying to pull a fast one by having the servers on tribal lands, but offer the games statewide. That’s how internet-anything works. There’s a central server allowing for users from all over a geographic area to connect. The limitations of that geographic area are set by laws. Welcome to 1997.)

If the proposed legislation passes as written – and that’s a very big if at this point – Gov. Kay Ivey would be authorized to enter into a negotiation with the Poarch Creeks to determine what games can be offered at casinos, the types of wagering and the annual fee due from PCI to the state for the right to operate those games. That’s the way this works.

Speaking of which, that brings us to the first claim in Murdock’s warning letter – that the Poarch Creeks could finagle a way to get a casino in Baldwin County, Birmingham or Huntsville. His email also gives pretty good insight into the three biggest opponents to the gaming legislation – Sens. Chris Elliott, Jabo Waggoner and Sam Givhan – since those three are warned specifically of this super-secret “barb” that could land a casino in the districts they represent. (A reality that the people who live in those districts are not opposed to.)

However, Murdock’s claims are, to be blunt, ridiculous.

Now, I’m not going to get too deep into the weeds of Indian Gaming laws, but here’s something that’s very important: the only lands immediately eligible for tribal gaming are lands held in federal trust prior to 1988 by a federally-recognized tribe. All other lands acquired and held in federal trust post-1988 must be approved for gaming by the governor of the state in which they are located.

In his email, Murdock uses a lot of legalease to make the argument that that’s not technically true, invoking the “supremacy clause,” several federal statutes and the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act to substantiate his claims. It’s smoke and mirrors, and he knows it.

Basically, his claim is that PCI has a bunch of lands acquired post-1988 that are now held in federal trust, and could acquire others, and those lands could be approved for gaming by a federal judge – one of those libs appointed by Obama and Biden. He actually invokes Obama’s name, because why not?

It’s laughable.

There’s an entire federal agency that oversees Native American issues, including gaming. Here is the literal language from that agency’s website for what happens if a state’s governor doesn’t agree to allow post-1988 lands for gambling:

- If the Governor provides a written non-concurrence with the Secretarial Determination:

(1) The applicant tribe may use the newly acquired lands only for non-gaming purposes; and

(2) If a notice of intent to take the land into trust has been issued, then the Secretary will withdraw that notice pending a revised application for a non-gaming purpose.

But Murdock’s claims are actually much more ridiculous when you consider one other small issue: the governor of the state has authority over the entire compact process. If Ivey were to decide in the middle of negotiations that she just didn’t want to do it anymore, it’s dead. Right then.

The entire federal government approval process for Class III gaming – games above electronic bingo – hinges on state approval. It was set up in order to give states significant power in the process because states will be forced to spend significant tax dollars to regulate that gaming and address various issues associated with it.

To suggest that a court anywhere would simply undo the entire basis of the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in order to force Alabama to allow casinos in locations where state officials don’t want them is ludicrous. And yet, here is a former justice doing just that.

But not just that. Murdock is sending his thoughts to lawmakers, and in the same email encouraging them to give him a call so they can talk about his concerns in depth. All while apparently being paid by anti-gambling groups. (He has written several pieces for API, which has established itself as firmly anti-gaming.)

It’s a familiar pathway for gambling legislation in this state. A decent piece of legislation will come along. It will gain support. It will have massive support among voters. It will draw the attention of out-of-state casino owners and gambling interests, which benefit significantly from the influx of Alabama residents traveling to their states. Those entities will pay for negative attacks on the legislation, including underhanded tactics such as misconstruing the complex laws and the “real” objectives of the proposed legislation.

The House bill that passed that chamber so easily would have allowed voters to approve gaming that would bring in more than $1 billion annually for the state, resulting in college scholarships, infrastructure spending and the expansion of rural health care services. A handful of senators have already blown that up, because they’re beholden to special interest groups or don’t understand the basics of the laws they’re voting on. And now, even the trimmed down substitute might be too much.

In the meantime, Alabama is overrun with illegal gaming. State residents spent more than $2 billion wagering on sports last year alone. One small electronic bingo casino in Greene County brought in more than $50 million in profits in 2021. We’ve had 12 rural hospitals close in recent years and we’ve sent millions of Georgia, Tennessee and Florida kids to college for free.

And now you know why we’re in this shape.