|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The Autauga-Prattville Public Library has been plunged into chaos since it adopted new policies that would prohibit books including gender identity, sexual orientation, and sexual conduct for minors under 18.

On Thursday, freshly appointed Alabama Public Library Service board member Amy Minton proposed a new set of code changes for the state agency that would require all libraries across the state to implement those policies basically verbatim.

In her first meeting as a board member, Minton made a motion to either start a new 45-day public comment process on her code or consider it as a possible amendment to the current changes proposed by Gov. Kay Ivey.

APLS executive secretary Vanessa Carr reported that 499 public comments have been submitted so far and 399 of those are opposed to changing the policy. Only 17 were in favor of the changes. It’s not clear what the remainder of public comments state. APR has begun the process of requesting these records. Those figures represent a nearly 80 percent disapproval rate of the proposed changes, while a meager 3 percent support the changes.

Those Prattville policies were written with the “involvement” of attorney Laura Clark, leader of the Alabama Center for Law and Liberty and once an active advocate for Clean Up Alabama. The ACCL is an offshoot of conservative think tank Alabama Policy Institute, which also spurred the right-wing media site 1819 News.

The policies themselves have not yet been put into action, at least not fully, but the library board fired Director Andrew Foster for failing to move books (or for sharing emails with the press, or for recording an executive session depending on the time and day APPL Board Chair Ray Boles is asked about it).

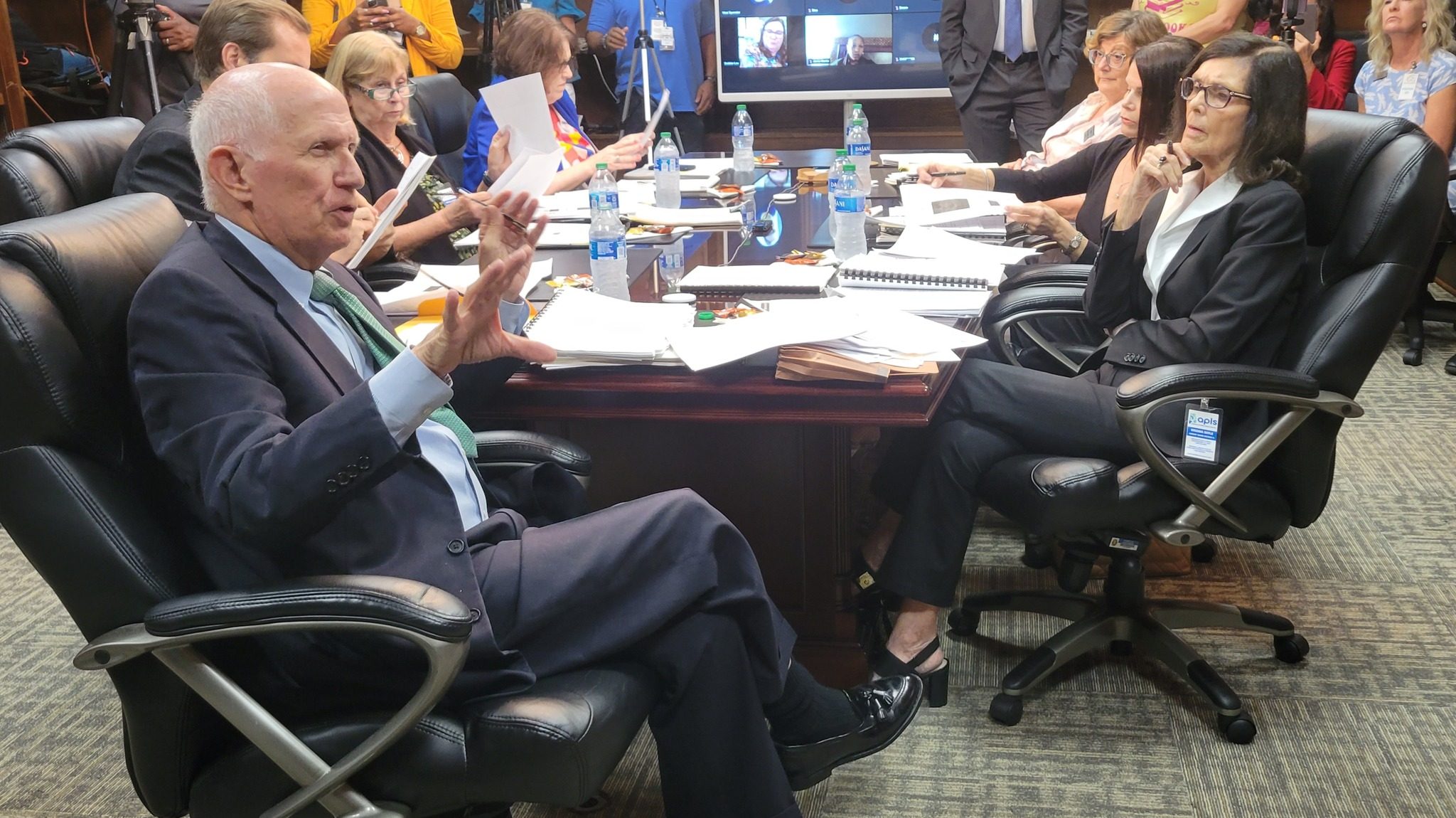

Nobody on the APLS board mentioned the obvious background of the proposed code changes—APLS Board Chair Ron Snider said he turned down requests for residents to make public comments at this meeting about the Prattville situation because of a long agenda and because the happenings in Prattville are more of a “local matter.”

“We certainly follow the news about what is happening in Prattville, and we are always concerned when there is discord in a library,” Snider said .”But we believe those are local matters that we have no authority over.”

The issue could come on the agency’s radar, however, if it fails to comply with the requirements for state aid; that hasn’t become an immediate problem, but Snider said if it does down the line, the board will have to take that into consideration. The library nearly did put itself into conflict with state aid requirements, announcing Monday that it would reduce hours of operation to 42 hours a week due to a sudden workforce fallout, only to realize that the reduced hours fall short of the APLS requirement of 45 hours a week for a library in an Autauga-sized community. Volunteers, largely members of Clean Up Alabama, have been running programs to keep the library eligible for state aid.

ALGOP Chairman and APLS board member John Wahl amended Minton’s motion by suggesting the formation of a subcommittee to rework the proposal, citing concerns that the agency may lack the authority to implement some of the changes as written.

Wahl suggested the subcommittee on the project be himself, Minton and the other fresh Ivey appointee, Deborah Windsor.

Director Nancy Pack pushed back that she thought a more senior member of the board should be involved in the subcommittee, and Snider agreed, switching in longstanding member Angelia Stokes for Windsor.

The proposed policies align with Prattville, and requests from Clean Up Alabama

In a Feb. 28 email, Clean Up Alabama told its supporters to tell Gov. Kay Ivey and the APLS board “Thanks, but no thanks.”

“… first, it is important we mention our gratitude to Governor Ivey for publicly addressing the issue of inappropriate content for children in our public libraries. likewise, we are thankful that the APLS Board of Trustees saw fit to make the suggested changes by the Governor,” the email states. “However, we asked for clear, common sense changes that would make state funding to local libraries contingent on the implementation of policies that will protect minors from exposure to sexual content. These changes do NOT accomplish that request.”

In that same email, the group sets its standards for what the APLS code should require instead.

“The changes to the administrative code should include: materials selection policies that specify that materials for minors shall not include content with obscenity, sexual conduct, sexual intercourse, sexual orientation, gender identity or gender discordance; necessary safeguards that prevent the exposure of minors to sexual content; and no public funds toward ALA memberships, trainings, or other resources.”

And … check and check and check—the code proposed by Minton hits each and every one of those requests; not surprising as Minton has been open and honest about her desire to see LGBTQ and sexual content removed from sections for minors including by challenging 30 books at the Gadsden Public Library.

“… the library shall not purchase or otherwise acquire any material advertised for consumers age 17 and under which contain content including, but not limited to, obscenity, sexual conduct, sexual intercourse, sexual orientation, gender identity/ideology, or gender discordance,” the proposed changes read. “Age-appropriate materials concerning biology, human anatomy, or religion are exempt from this rule. Books with the word kissing or the word rape in and of themselves should not be excluded.”

Here’s the Prattville policy for comparison: “… the library shall not purchase or otherwise acquire any material advertised for consumers ages 17 and under which contain content including, but not limited to, obscenity, sexual conduct, sexual intercourse, sexual orientation, gender identity, or gender discordance. Age-appropriate materials concerning biology, human anatomy, or religion are exempt from this rule.”

Unlike the Prattville policy, the proposed APLS code changes specifically would add that books containing the prohibited content “should not be located in designated areas for children and teens.” That lack of clarity added to the confusion in Prattville, as the new policies there prohibited books from coming in, but gave no impetus to the director to move books that had already been approved for those sections.

The proposed changes would also require special library cards for minors that ensure they cannot check out any such material. The essence of the policy mirrors Prattville policy, although the verbiage itself differs in parts. This portion of the policy seems to satisfy CUA’s request for “necessary safeguards that prevent the exposure of minors to sexual content,” although it notably reaches beyond sexual content into LGBTQ content.

The proposed changes also include language to ensure libraries don’t see blocking children’s access to these materials as censorship, and expressly prohibiting the expenditure of any “state, county or city funding” from being made to the American Library Association. That rounds out Clean Up’s request.

It’s currently unclear what Ivey’s position is on these new proposed code changes. APR reached out to Gina Maiola, spokesperson for Ivey’s office, who said she would have to look into the situation. On the one hand, Ivey firmly suggested the changes currently undergoing a public comment period as a solution that balanced “Alabama values” and local control. On the other, Ivey just appointed Minton—whose policy ideals should have been clear—and Windsor, who apparently agrees.

Wahl requests APLS to create template policies, “library bill of rights”

Minton told her fellow board members that she walked into an Alabama library in her district and one of the librarians quickly took down the ALA’s “library bill of rights” from where it was framed on the wall.

“I know, I know—we’re taking it down,” Minton said the librarian told her.

There is no need for any library in the state to turn away from the ALA library bill of rights if they don’t desire. The APLS dissociation in no way prevents state libraries from being institutional members of ALA or the Alabama Library Association, nor does it prevent libraries from utilizing ALA resources from webinars to, yes, posting its bill of rights. The only mandatory departure from the ALA library bill of rights is that, in Alabama, parents have the legal right to view their children’s circulation records.

Minton told the anecdote cordially, but it represents a state of confusion that has come in the wake of the changes the APLS has been grappling with and the sometimes blurry understanding of the agency’s purely advisory role outside of the requirements for state aid.

One of Wahl’s major priorities when withdrawing from the American Library Association was ensuring the severing of ties doesn’t result in local libraries losing certain resources. Again, state libraries can currently continue to use ALA resources if they want.

Pack informed Wahl that most of the resources local libraries use ALA for do not come through APLS, and described many of the day-to-day operations in which that is handled. As for policies, Pack said the best method would be for individual libraries to work with the agency’s seven traveling consultants on what policies work for them, which she reiterated is something already being done.

“I was talking with one local librarian when I was speaking in an event at who was very, very excited to talk to me, thank me for my work toward the safety…,” Wahl said. “It’s a very rural, very small library and she’s excited about wha the board is doing.”

APR could not arrange an interview with Wahl for this story, but Wahl is working with APR on a follow-up.

When Wahl suggested that the board could create a subcommittee to look at crafting the template policies, Pack challenged him, stating it was her duty as the librarian to be the one creating such policy and not the board.

Wahl’s initial motion included creating the template policies and a library bill of rights, but the more senior members of the board said they weren’t sure whether the agency should delve into making template policies. Wahl pushed to have his motion honored, but the motion failed in a 3-3 tie. Snider, Stokes and Michelle Hughes voted against the motion while Wahl, Minton and Windsor voted in favor.

With that motion dead, Wahl moved solely for the APLS to craft a library bill of rights, which the board approved unanimously. Pack said that can be ready by the next board meeting.

APLS funding is on the line

Wahl reported on the status of the agency’s funding request, stating that he had spoken with House Education Budget Chair Danny Garrett, R-Trussville, and requested level-funding.

But there was “pushback,” Wahl said, due to Garrett’s concerns about “what’s happening in Alabama libraries.”

When Pack asked Wahl whether that meant Garrett is looking to cut funding, Wahl said nothing was final right now and that conversations are still being had among lawmakers.

Wahl said that Garrett hoped the state agency could alleviate his concerns and give him the confidence to level-fund the APLS, but Wahl suggested the board’s failure to fully commit to creating new template policies may hamper that.

“He had things he would like to see addressed,” Wahl said.

APR sent a message to Garrett for comment, but had not received a response before publishing time. APR will continue to pursue comment from Garrett for this or future articles.

Wahl did not quantify the threat to state funding of public libraries, and it appears Garrett did not either. A reduction in state aid funding for local libraries would hurt the smallest libraries the most, while most big-city libraries could afford to operate without state aid,