|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

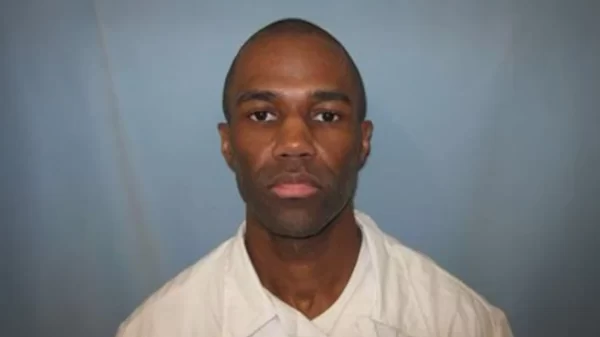

Later this week, unless the extraordinary happens, the State of Alabama will execute Kenneth Eugene Smith. His case, entangled in a web of legal technicalities and ethical debates, epitomizes the complexities and contradictions of the American justice system. Smith, convicted in a 1988 murder-for-hire plot resulting in the death of Elizabeth Sennett, faces execution by nitrogen hypoxia, a method untried and raising serious concerns about its humaneness.

The impending execution highlights a critical issue: The 2017 legislative decision in Alabama to abolish judicial override in death penalty cases. This practice, once allowing judges to impose death sentences against jury recommendations, was deemed improper by the state’s predominantly Republican Legislature and Gov. Kay Ivey. Not surprisingly, Smith’s own death sentence was a product of this very practice. His first conviction was overturned, and upon retrial in 1996, a jury recommended life imprisonment. Yet, a judge overruled the jury, sentencing Smith to death. How can Alabama, having recognized the flaws in judicial override, persist in upholding a sentence now considered unjust by its own laws?

The 2017 law, unfortunately, wasn’t made retroactive. This leaves the question: Is there such urgency in executing Smith that his fate couldn’t be stayed for a reconsideration by the legislature? This rush to execute before revisiting a condemned practice not only appears hypocritical but also cruel.

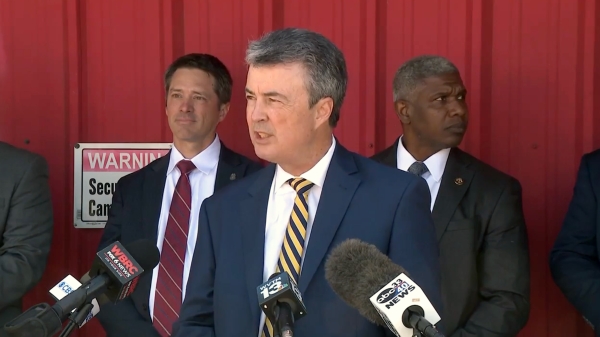

Attorney General Steve Marshall, a former Democrat and Obama supporter turned conservative, seems to be using capital punishment as one means to reshape his political identity. However, Gov. Ivey, often commended for her wisdom, faces no such political dilemma. Over a hundred faith leaders are rallying, urging her to demonstrate mercy and halt the execution. Their plea resonates with a broader humanitarian concern: The death penalty, fundamentally, is more about vengeance than justice. There’s scant evidence suggesting that it deters crime more effectively than life imprisonment.

The state’s rationale for adopting nitrogen hypoxia – that it has a supposed quick and painless effect – is under intense scrutiny. Smith’s attorneys, appealing to federal courts, warn of potential horrors if the execution goes awry. These fears aren’t unfounded; the state’s previous attempt to execute Smith was a gruesome failure.

At the heart of this issue is the principle of retroactivity. When Alabama abolished judicial override, it implicitly acknowledged its injustice. By not applying this change retroactively, the state maintains a perplexing stance: Endorsing a principle for the future while ignoring its implications on the past. It’s a selective application of justice, one that undermines the legal system’s integrity.

Alabama has an opportunity to exhibit not just logic but also mercy. It isn’t about undermining the severity of Smith’s crime but about ensuring that the state’s actions align with its current understanding of justice. This case isn’t merely about one man’s fate; it’s a litmus test for the state’s commitment to equitable and humane legal practices.

Kenneth Eugene Smith’s impending execution raises profound questions about justice, morality and the evolution of legal standards. Alabama, having recognized the fallacy of judicial override, now faces a critical choice. Will it adhere to a newfound understanding of justice, or will it proceed with an execution that contradicts its own legal principles? This is not just about Smith or the heinous crime he committed; it’s about the kind of justice system Alabama aspires to embrace– one that fails to correct past mistakes or one that learns from its past to create a fairer, more humane future.