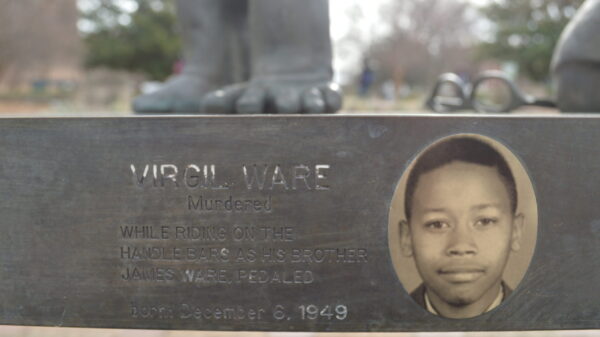

During a trip to Montgomery last weekend, I learned that I might be related to a lynching victim: William Person of Wake Forest, N.C.

He is one of the people memorialized on the front wall of the Equal Justice Initiative’s Monument at the Peace and Justice Memorial Center, across the street from the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. It’s very likely we’re related. My Uncle Phil says we have extended family in that part of North Carolina.

Also, the name William Person is well-established in our branch of the family. One of my uncles and a first cousin share the name.

In the spirit of comity that Black folks have historically extended to each other in defining family, I will be calling this man Cousin William for the remainder of this column. Because even if he wasn’t my cousin, he could have been. And that’s good enough for me.

Unfortunately, Cousin William’s life has been defined totally by the details of his death. According to EJI, he was shot and killed by a white man who wanted him to spend a day working for him. The white man cut the deal with Cousin William’s employer.

But he wanted no part of that deal. Cousin William objected and ran away.

He had to have known that he was signing his own death certificate. Jim Crow etiquette was clear: no disrespect of white people, in no form. Do as you’re told or else.

No back talk. No objecting and running away.

So why did he do it? Had Cousin William worked for that man before? Did he know that he was going to be unusually brutal or cruel?

The motivation to run had to be spurred by something stronger than merely a desire to go swimming, fishing, or hunting. Or even wanting to spend time with his family.

My guess is that Cousin William knew that this white man was more cruel or sadistic than his regular boss. EJI’s online report, Lynching In America, details the cruel conditions black men were subjected to under the convict leasing system. The report references findings by a Hinds County, Miss. grand jury in 1887: “Six months after 204 convicts were leased to a man named McDonald, twenty were dead, nineteen had escaped, and twenty-three had been returned to the penitentiary disabled, ill, and near death. The penitentiary hospital was filled with sick and dying Black men whose bodies bore “marks of the most inhuman and brutal treatment . . . so poor and emaciated that their bones almost come through the skin.”

As far as we know, Cousin William wasn’t a convict who had been leased out for work. But who’s to say that similar conditions might not have been awaiting him. And knowing that, he preferred the consequences for objecting and running.

I give this theory credence for at least one reason. When Cousin William ran, the white man for whom he was to work reportedly suggested that he would run faster if someone was shooting at him.

So, he grabbed a rifle and fired. Cousin William died of two gunshot wounds.

The unnamed killer had to have been an incredibly callous, cynical, evil person. Maybe Cousin William had known that and settled up with the Almighty – conceding that there was a fate far worse than death.

It wouldn’t be the first time Black people have made such a choice. The Middle Passage between the West African coast and the Americas was where some Africans launched themselves into the sea rather than continue to endure severe cruelties on slave ships – or see what horrors awaited them here.

Cousin William’s killer suffered a white man’s fate for 1959. He never served a day in jail. He paid Mrs. Cousin William less than $3,000 as restitution – probably not even $30,000 in today’s dollars. No small amount, but surely a husband’s life is worth much more than that.

Seeing this familiar name in such a troubled but sacred space is a little jarring. But it’s also a stark reminder that many other Black families carry this history. Even if their loved one isn’t a name famously etched into a wall.