|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

As we approach the August 14, 2023 federal court hearing on reapportionment, there has been heated debate concerning the fairness of maps relating specifically to a concept called “communities of interest,” a central component of drawing fair districts.

Community of interest and fairness are seemingly words that should be paired together. However, in the debate surrounding Alabama’s redistricting map, as ordered by the SCOTUS, the words are distinctly hollow in the GOP-drawn map which circumvented the varied connections between the Black Belt and the Gulf Coast.

For me, like countless other Blacks in Mobile, the Black Belt is the air of our foundation, threading character, strength and pride. The qualities are our community of interest, much like the red clay dirt of the Black Belt seeds our neighborhoods in Mobile. Ironically, the value of voting was birthed by a mother from Dallas County who proudly recounted the virtues of growing up on the Alabama River.

Though I do not presume my legacy represents all Blacks in Mobile, I would be willing to bet the vast majority in Mobile have roots that identify with the Black Belt. From poverty to other ills that are plaguing Mobile Blacks, there are a multitude of factors that make it representative of the Black Belt. It has been a community of interest for countless generations.

In order to ensure fairness and that the “one man, one vote” principle is applied in practice, there are a multitude of criteria to consider in drawing fair districts. This is because for “one man” to truly have “one vote,” those votes must be of “one value” – the same value. This is the central purpose of the reapportionment process.

The process includes equal population requirements, ensuring that districts are contiguous so that all parts of the district are connected to each other, respecting natural geographic boundaries, and many other factors. The process also includes guidelines that “communities of interest” should be preserved within the same district or should be minimally split between districts.

The reason that “communities of interest” can be controversial in reapportionment is because the term is subjective. And, unlike an easily observable fact such as ensuring that all parts of a voting precinct are contiguous, the concept of a “community of interest” is more open to interpretation and perspective.

This is particularly true when it comes to understanding the city of Mobile and its dual roles as the watershed of the Black Belt and the crowning city of our Gulf Coast region.

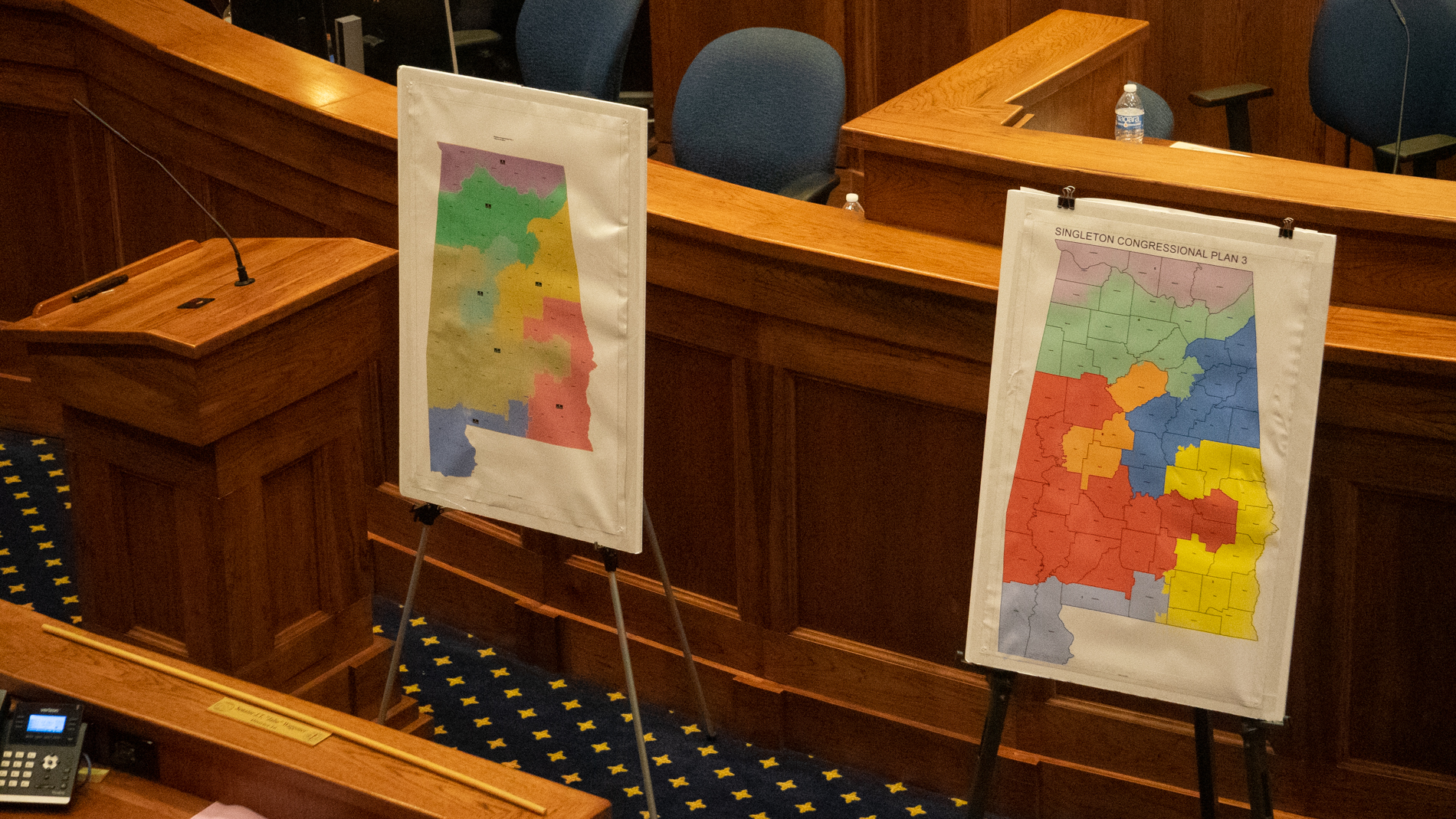

For background, the majority of the Alabama Legislature adopted Senate Bill 5, also known as “Livingston Plan 3”, on July 21, 2023. This map was supposed to remedy our noncompliance with Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, by creating a second majority-Black congressional district, or “something quite close to it,” in the words of the federal courts.

However, the map adopted by the majority creates a second district that contains just below 40 percent Black voting-age adults – quite far from the court’s requirement. The majority rested its argument largely on their understanding of the principle of “communities of interest,” a mistaken understanding that demanded that Mobile County and Baldwin County remain in the same district.

Simply put, the majority diminished the focus on people, and instead shifted that focus on economy and infrastructure and, most disappointingly, political gain. And, in those same redistricting guideline revisions, the majority moved the goalposts on “communities of interest,” in a way that supports the twisted map that fails to satisfy the Voting Rights Act.

Having lived in Mobile for almost my entire life, and having family in the lower portions of the Black Belt, I know the deep connections we share with the Black Belt. Mobile is the watershed of the Black Belt; it is where the slaves came in and went up to labor, and where the cotton came down to be shipped out. It is the land of the Clotilda, it is the land of Africatown, it is the closest connection to the land of our forefathers. For those whose ancestral past was severed from them, Mobile may be the closest they ever come to finding “home.”

This connection is still alive today. When my relatives in Washington and Monroe Counties – both firmly in the Black Belt – moved to “the City” for work, they meant they were moving to Mobile. The “contiguous, compact” Black population identified by the federal courts extends into Mobile County unbroken, a living testimony of that human connection. Mobile has, more often than not, been included with lower Black Belt counties in congressional districts throughout our history. And, in the current School Board districts, the Northern part of Mobile County is included with those counties in recognition of that connection.

This is the connection we are supposed to focus on when discussing “communities of interest” – the people. Voting is about the people, and this recent Supreme Court case was about the people.

The case for Mobile County to be wholly included with Baldwin County and other Gulf Coast counties is based not on the people, but on economic interests and political priorities. In the new redistricting guidelines adopted by the majority, only one sentence was spent on the description of the Black Belt, but four pages were dedicated to the economies of the Mobile and Baldwin areas. These guidelines echoed the testimony of Alabama’s witnesses before the Supreme Court, testimony which Chief Justice Roberts described as “partial, selectively informed, and poorly supported,” and asserted was “‘simply’ to preserve ‘political advantage.’”

In fact, when asked during the House debate how Mobile and Baldwin counties constituted a community of interest, the response from Rep. Chris Pringle (R-Mobile) was dismissive when he said, “They share the same roads.”

Mobile and Baldwin Counties certainly have shared history throughout the colonial period and beyond, as relied upon by the majority. Indeed, Mobile and Baldwin have remained together throughout fluid changes in political boundaries of colonial nations. But, that shared history is no different and is no more worthy than the shared history among other areas of the state, such as areas that remained together throughout changes in tribal lands, county reorganizations, and population shifts. The Supreme Court echoed this when they declared that they “do not find [Alabama]’s argument persuasive” enough to keep Mobile separated from the Black Belt.

By understanding that the importance of preserving communities of interest is far more than just sharing roads, we hope that the federal court will reject the “Livingston 3” map that clearly defies the Court’s order. All we are asking for is fair maps and for Black voters to be able to elect the candidates of their choice.

That should be of interest to everyone in our Alabama community.