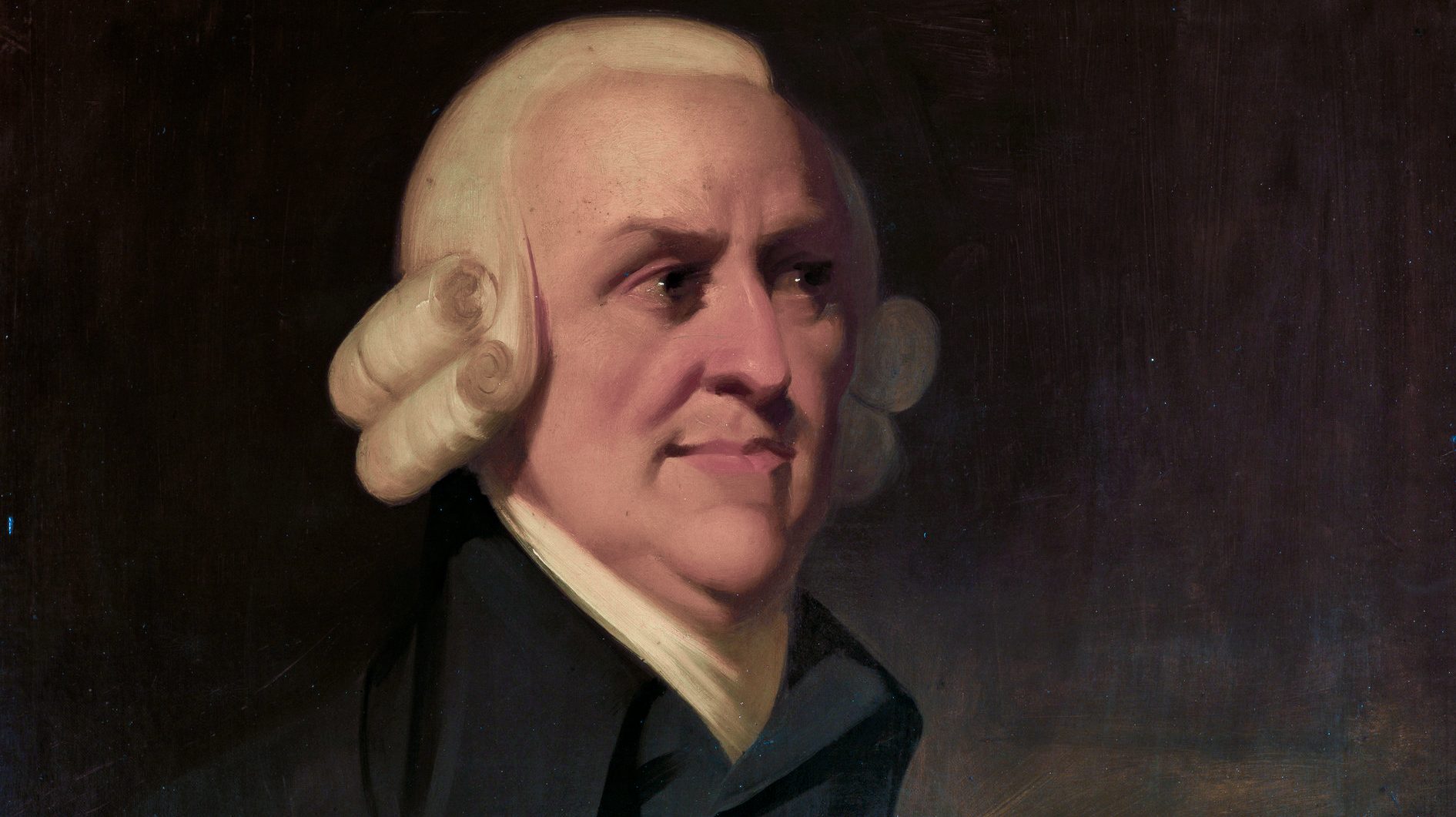

Adam Smith, the anchor of that group of inquisitive Scotsmen who spawned the Scottish Enlightenment and significantly changed the world, was born 300 years ago this month.

The era of his birth was still primarily agrarian with superstition superseding science. He would alter this status by observing his community, pursuing the life of a scholar, and questioning his experiences in the world around him. And…… he wrote his thoughts down.

Scotland was ready to nurture the likes of Smith. With an expanding middle class, his community was beginning to prosper and grow. Smith would want for little and had the resources to think about his world and consider both the nature of man and the means to achieve a happy existence.

The foundation for his community was based in many respects on the political, social, and legal framework that originated in the Magna Carta. Indeed, the structure established by Magna Carta produced several results that were the basis for a portion of Smith’s theories about wealth and prosperity.

Smith was never content to accept the world as he found it. He asked probing questions and considered thoroughly the looming issues of his day. He was a practical academic who would pay close attention to the world around him. He noticed what worked, what failed, and what made people successful.

Initially, his observations were contained in academic lectures which Smith, a prolific writer, eventually turned into books that are still in print and studied today.

His first major work was “A Theory of Moral Sentiments,” which was Smith’s attempt to understand and explain human nature. He theorized how people could lead a balanced life between unbridled self-interest within the constraints of self-control but with sympathy and compassion for others. From a view of how individuals lived in community and how they behaved together, Smith realized that certain principles emerged that created a prosperous environment and happy citizenry.

From these observations came the book for which Smith is most famous: “An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations,” or “Wealth of Nations,” for short. From its publication even until today, the book is quoted, misquoted, and used to justify any number of ideas – both good and bad. Indeed, the problem with writing a philosophical book that is more than 1,000 pages is that there is something for everyone to embrace or reject. And, when read in conjunction with Smith’s other works, like any inquisitive scholar, his “Wealth of Nations,” when taken out of context, appears inconsistent.

Smith was not necessarily an original thinker but had the presence of mind to write down his thoughts. Others might have introduced the idea, but Smith teased our various concepts and risked his reputation by exposing his musings for critique and inquiry.

“Wealth of Nations” made numerous observations about the commercial world and posed explanations of prosperity. Smith noticed it made little sense for people to be jacks of all trades and observed that individuals had different skills sets that made them better at some things than others. He posited that once labor was divided into specialized tasks, products were more efficiently produced, prices were lower, and prosperity seemed to abound. His work then encouraged specialization so that industry could produce goods more efficiently.

Another observation was the importance of self-interest. Smith detected that the reason people worked hard was to promote their own well-being. This pursuit of selfish aims not only benefited the self-seeker, but also created a commercial environment prospering the entire society. He saw trade not as delivering a mere service, or a zero-sum game, but as workers collectively seeking to improve their financial status such that they worked harder to sell more products, which worked to lower prices for consumers.

He further reasoned that for a nation to prosper, government should allow as much freedom as possible so that individuals can pursue their self-interest. Smith was concerned that the restraints on industry be it by regulation or taxation could reduce productivity. This was a real concern in his day as guilds might restrict by license who could produce what goods at what price. Guilds served to stymie innovation and productivity that occurs when laborers, motivated by profit, develop more efficient means to produce more goods.

Smith also saw that taxation from government created disincentives to work hard. If people were taxed too much and lost their hard-earned profits, they would have no reason to find new ways of production and expand their business.

So, when Smith looked at Scotland and noticed the prosperity, he reasoned that commercial success from individual employment to business owners was almost magically motivated. He theorized that an invisible hand rewarded a society that had the most freedoms to allow business to sell and consumers to buy with few limitations to restrain open and free markets.

Another, equally critical part of prosperity was having a stable, reliable, and consistent system of justice. Unlike other countries, Scotland had just this. Magna Carta had planted seeds that established legal structures to create economic dynamism in one instance by limiting any infringement on the “ancient liberties and free customs” that allowed trade to flow in and out of London. It further sought to reduce restrictions of the use of waterways to transport goods among cities. Free trade was also supported by requiring a consistent system of weights and measures throughout the land.

Adam Smith’s genius was to look around and see why his country was prosperous and speculate on the root causes of economic success. “Wealth of Nations” was not a guide to prosperity, but, rather, it was an observation that if a country, state, or community wants to achieve commercial success, there are obvious means to accomplish it.

When grounded in a government that supports specialization and free movement of labor, limits regulation, restrictions, and taxation, and fosters a reliable legal system, a magic, invisible hand almost spontaneously creates commercial success.

No wonder his legacy is still debated.