|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Before she was set to walk across the stage and receive her high school diploma this month, L.B. was called into the principal’s office at Harrison Central (Miss.) High School. There, a mere two weeks before graduation, she was told that unless she attended the ceremony in a traditionally masculine shirt and tie, she would be unable to participate.

L.B., a transgender female who has worn dresses to class, prom and other official events, refused.

“Me going to graduation in what they asked me to wear would be me telling them that it’s OK, and it’s not. It would just feel like I was shadowed and tainted by bigotry, hate,” L.B. told Biloxi’s WLOX. “My graduation, it’s the start of a new life, a better life.”

Together with the ACLU, L.B. and her mother filed suit against the school district, arguing for a temporary restraining order that would have allowed her to attend graduation wearing a dress and high heels. However, a federal judge ruled for the school district the day before the May 20 ceremony, and L.B. did not attend.

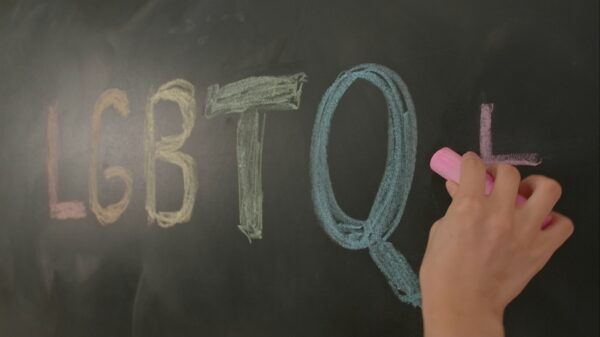

Half a country away, 12-year-old Liam Morrison and his family are also suing their local Middleboro, Massachusetts school district — because Liam was sent home last month for wearing a shirt that said, “There are only two genders.”

“This isn’t about a t-shirt,” said Alliance Defending Freedom Senior Counsel Tyson Langhofer in a news release announcing the lawsuit. “This is about a public school telling a seventh grader that he isn’t allowed to hold a view that differs from the school’s preferred orthodoxy. Public school officials can’t censor Liam’s speech by forcing him to remove a shirt that states a scientific fact. Doing so is a gross violation of the First Amendment.”

These two cases are but skirmishes in the wider culture war that has centered itself (for the moment) on transgender people. Whether it’s Target or the Alabama legislature concerning itself with the perceived fairness of athletic playing fields, it’s evident that we are having some sort of moment in which conservatives and others with clout are finding it convenient, advantageous or simply all too easy to attack a vulnerable population with little access to the levers of political power. And while this wave of brazen bigotry is new, the tools to judge it — at least when it comes to student speech cases like those of L.B. and Liam — are the same ones we’ve had for the better part of a century.

While American students have long sought redress in the courts (such as a 1919 Iowa case over a graduating senior who refused to wear an odorously fumigated cap and gown or a 1923 Arkansas suit by a female student who was suspended for wearing talcum powder on her face), the legal standard for deciding public school student speech cases is the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, a 1969 case that upheld the right of high school students to wear black armbands to protest the Vietnam War. In Tinker, the Court recognized the rights of students to engage in speech — especially political speech — on school grounds so long as the expression did not cause a “material and substantial” disruption with school operations.

But loose interpretation of the Tinker disruption standard by lower courts coupled with the decision’s own clarification that the war protest armbands did not “relate to regulation of the length of skirts or the type of clothing, to hair style, or deportment” resulted in most dress code regulations being upheld as constitutional. The Colbert County Board of Education’s school dress code, for example, cites as part of its legal justification a 1970 case out of Wetumpka in which a federal court upheld the authority of the school district to ban long haircuts for boys due to the disruption of gentlemen “combing, styling and arranging their hair in classes; being late for classes because they linger in the restrooms combing their hair [and] congregating at mirrors provided for girls while combing their hair.”

And yet there is a speech interest in what we wear and how we present ourselves, and it doesn’t have to be as literal as the words on Liam’s shirt. For example, there may be nothing more central to L.B.’s personhood than her desire to communicate to the world around her that she is female — and to likewise be free of the school board’s compelled speech (in the form of a dress shirt and pants) that she is something that she is not. A Massachusetts state court held as much 20 years ago when it decided a transgender female student — one who had been subjected to daily inspections in the principal’s office — had the right to wear anything that other female students were allowed to wear. “[T]here is strong evident that plaintiff’s message is well understood by faculty and students,” the court wrote. “The school’s vehement response and some students’ hostile reactions are proof of the fact that the plaintiff’s message clearly has been received.”

Assuming that L.B.’s wish to wear a dress under her graduation regalia is sufficiently communicative to be protected as speech, she should have been allowed to do so as a matter of law — one district court judge’s conclusion notwithstanding. She would not have disrupted the graduation ceremony as per Tinker’s requirement, nor would she have stood out from other female graduates in such a way as to alter the traditional message of a school-sponsored graduation, which distinguishes her case from one in which a South Dakota court found that a graduate had no right to wear traditional Lakota garb instead of a graduation cap and gown.

Turning to Liam’s shirt, it too is likely protected under the law because whatever distraction it might cause in the school setting fails to meet the Tinker “material and substantial” disruption standard. Many courts have upheld the right of schools to ban divisive symbols such as Confederate flags and gang paraphernalia because of tensions they can exacerbate. One California school district was even permitted to ban American flag clothing when it was done in reasonable fear of school safety. (Schools have a far greater ability to control speech under this formulation than other arms of government. The Confederate flag, for example, remains legal, protected speech in every other realm of public life.)

Liam’s shirt, while divisive and offensive, falls short of a systemic issue confronting his Middleboro school and instead represents an attack on any fellow students who might fall along a gender spectrum. Here, the best analogy is to cases in which students wore homophobic shirts to school, and courts have been less unified in their outcomes. The Ninth Circuit found for administrators in one such case, holding that, “Public school students who may be injured by verbal assaults on the basis of a core identifying characteristic such as race, religion, or sexual orientation, have a right to be free from such attacks while on school campuses.” The Sixth Circuit, however, concluded there was no “generalized hurt feelings” defense to First Amendment violations in the school setting as it upheld the right of a student to wear a shirt that read, “Be Happy, Not Gay.”

Assuming Liam’s shirt does not cross a line into direct and persistent targeted harassment (which would result in the sort of disruption to the educational process that Tinker does not permit), it is at the core of protected speech, especially given the cultural and moment we find ourselves in.

Perhaps in the fullness of time Liam will recognize that the shirt is ignorant and bigoted nonsense wrapped in the guise of his parents’ understanding of “science.” It’s more likely he won’t — since the people most central in his life have already set him down a path of intolerance.

The First Amendment, though, doesn’t permit us to government engineer our way to a more perfect society in Liam’s case.

But for one girl who only wanted to wear a dress to her high school graduation, Mississippi school administrators didn’t have to so actively and readily make her life worse.