|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

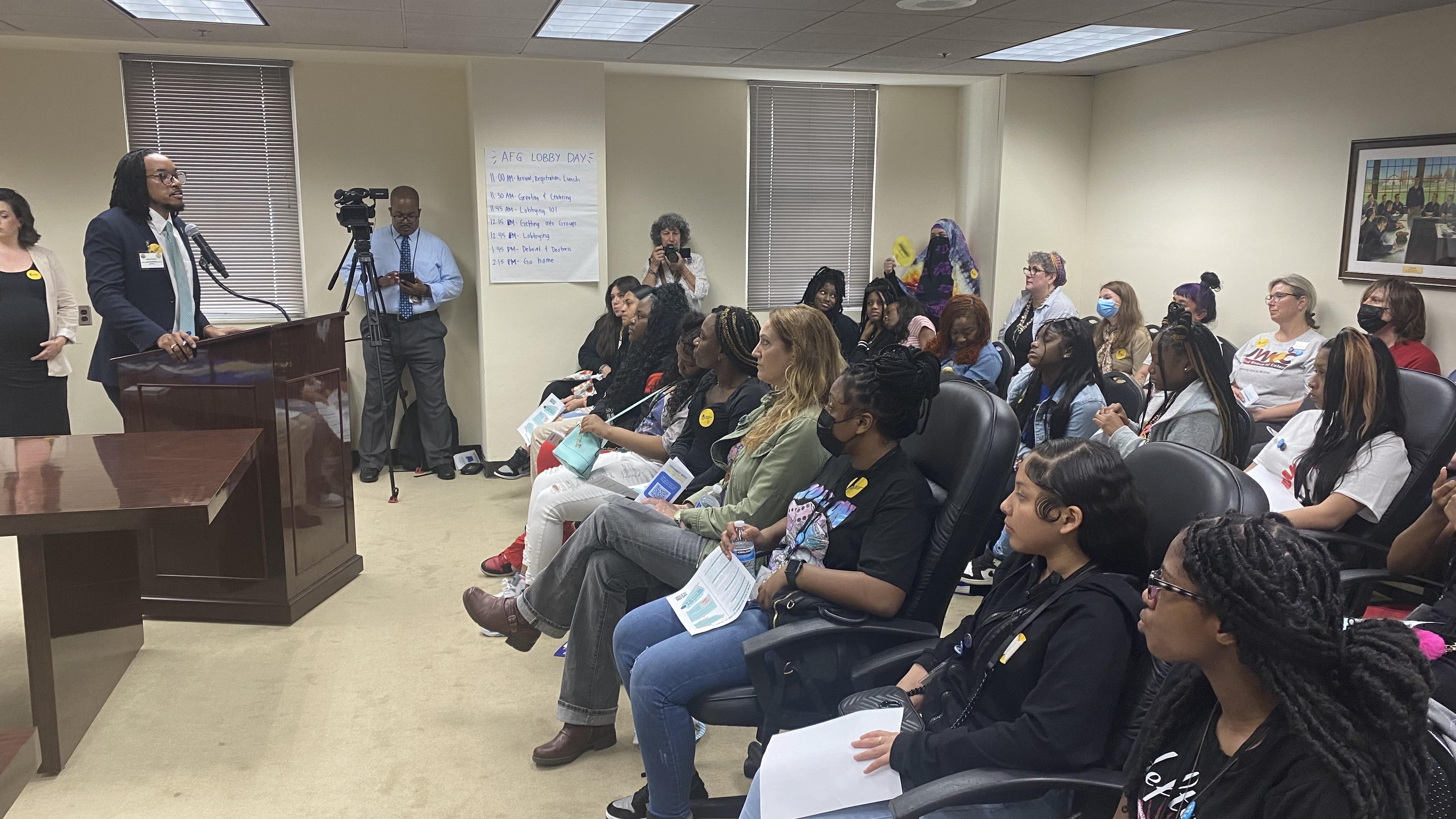

Advocates with Alabamians for Fair Justice gathered at the Alabama Statehouse on Tuesday to lobby lawmakers to support HB16, a bill from Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, to create an oversight process for the parole board.

England’s bill was sent to subcommittee during a House Judiciary Committee meeting in the previous week of the legislative session, but that did not deter advocates from pushing for the bill.

“We support more accountability for this board, which has been categorically denying people,” said Dillon Nettles, policy and advocacy director for the ACLU of Alabama. “Less than 10 percent of people who were before the parole board last year were actually granted parole. That is absolutely not sustainable, that is a problem; that is not how the process is designed to work.”

The approval rate from the board has had a well-documented precipitous decline from 53 percent in 2018 to now just 6 percent in this fiscal year. And in the first quarter of 2023, 97 percent of applicants have been denied.

Victoria R. Johnson, interim executive director for the Alabama Justice Initiative, said she would like to see the parole board go back to the “pre-Gwatney days.” Leigh Gwatney became the chair of the parole board in 2019 before the drop off in approvals.

But Johnson said she believes the real culprit behind the declining parole approvals is Attorney General Steve Marshall, who appointed Gwatney to the board.

The bill passed out of the House Judiciary Committee last year before Marshall came out in opposition to the bill, prompting England to pull the bill and work on gaining more support across the aisle.

This session, Republican members expressed multiple concerns about the bill, including Rep. Matt Simpson, R-Daphne, worrying that it would only expand bureaucracy.

Freshman Rep. Jerry Starnes, R-Prattville, notably called the notion that the parole board isn’t releasing anyone “is a hoax,” arguing that mandatory supervised release has left the parole board to only consider the “bottom of the bottom” applicants.

However, the parole board’s own guidelines, which take the original charge into account, consistently recommend the parole board release about 80 percent of the applicants going before them.

“We have a crisis with parole,” said Alison Mollman, senior counsel at ACLU of Alabama. “We have people who are ready to go home to their families, and they could do so consistent with public safety, but the parole board is not following their own rules and regulations.

“I don’t know about y’all, but in my experience when I don’t follow the rules, there’s consequences.”

But as it stands, the parole board’s guidelines are merely suggestions, and the board is not required to give any explanation for deviating from those guidelines and there is no appeal process.

England’s bill would temporarily create a council of nine members with various perspectives, including one member from the attorney general’s office, to create new guidelines for the board. Once those guidelines were made, the parole board would need to submit a detailed written explanation on why they chose to deviate from those guidelines and the applicant could appeal the decision to the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals.

The council formed to create those guidelines would be dissolved.