|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

A few years ago, as I sat on my bunk in the open dorm of Fountain Correctional Facility, I watched an incarcerated man construct a homemade prison knife.

My bunkmate, who was nearing his release date, sensed that something bad was about to happen. He quickly disappeared from sight. When he came back to his bunk hours later, I asked him where he had gone. He told me, “I thought war was about to break out. I’m not doing anything to jeopardize getting home to my family next month.” That man got out of prison a couple months later, and he has been a success story ever since.

I have spent over 30 years of my life locked up in the Alabama Department of Corrections. Over time I’ve learned a lot about how people operate in prison, and I humbly self-proclaim that I am an expert on the thinking patterns of incarcerated people.

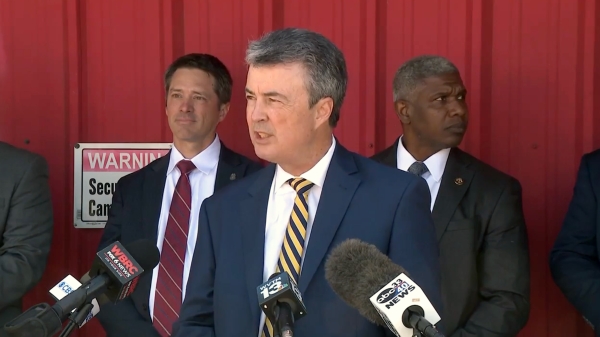

Despite what Attorney General Steve Marshall wants the public to believe, there are thousands of people inside of the Department of Corrections who want to keep their heads down and make it back to their families. They may have committed violent offenses in the past, but they have no interest in violence today.

I don’t often agree with Alabama politicians, whose prison stances have contributed to the U.S. Department of Justice filing a lawsuit against the state for unconstitutional conditions. But, I have to give Governor Kay Ivey credit for her January 9 executive order limiting the ability of Alabama prisoners accused of violations to earn time off their prison sentences.

Ivey signed this order in the wake of the tragic murder of Bibb County Sheriff’s Deputy Brad Johnson, who was allegedly killed by a man out on early release. This man had many disciplinary actions, according to Steve Marshall, including an attempted escape, where many are now claiming he should not have been eligible for good time. I agree his failure to maintain good behavior is a key factor.

Ivey stated in a news conference, “Our action today, very simply put, keeps violent offenders off the streets, incentivizes inmates who truly want to rehabilitate and better themselves, reinforces the concept that bad choices have consequences, and keeps our public safe.”

Governor Ivey’s move demonstrates that she has the wisdom to understand that she can be tough on crime and still make room for redemption for those who earn it.

Good time should be hard to earn and hard to keep. Yet eliminating good time entirely, as certain legislators propose to do during the 2023 session, will make everyone in Alabama less safe.

Just like when the Parole Board effectively shut down after Jimmy Spencer killed three innocent people in Guntersville, politicians run the risk of passing so-called “tough on crime” policy that actually serves no other purpose than vengeance. If vengeance is what we as a society want, then let’s just say that instead of pretending like reactionary policies contribute to public safety (and sentence everyone to death). They do not, and the reason for that is simple.

Human behavior almost always adheres to a simple truth: incentives shape our choices. When a person has no hope for rewards and cannot imagine being in a worse position than they currently are in, they have no reason to behave well. Nowhere is this principle clearer than behind the barbed wire of a prison fence.

Like Ivey, President Trump claimed he understood human behavior when he signed into law the First Step Act, which provides time credits for successful participation in recidivism reduction programs. Like any good businessman, Trump recognized that incentives could improve outcomes inside of prisons, contributing to actual rehabilitation of the 95 percent of incarcerated individuals who will return to society one day. Trump did something that Ivey did not, however. Time credit incentives at the federal level were made available to all prisoners serving more than one year and less than a life sentence. And that is important.

If Ivey believes in the executive order she signed, she should want to extend the incentive program to apply beyond the mere 15 percent of Alabama prisoners who are currently eligible for receiving good time. I would bet my freedom on the fact that allowing more people in prison to earn properly applied, good time would drastically improve conduct (violence, overdoses, and suicides) and reduce recidivism.

When people are given opportunities to improve themselves, we find out who will seize that opportunity and who will squander it. I, for one, would rather know who actually is committed to improving themselves and who needs more time to be rehabilitated before people are released from prison, not after they reach their mandatory parole or end-of-sentence date.