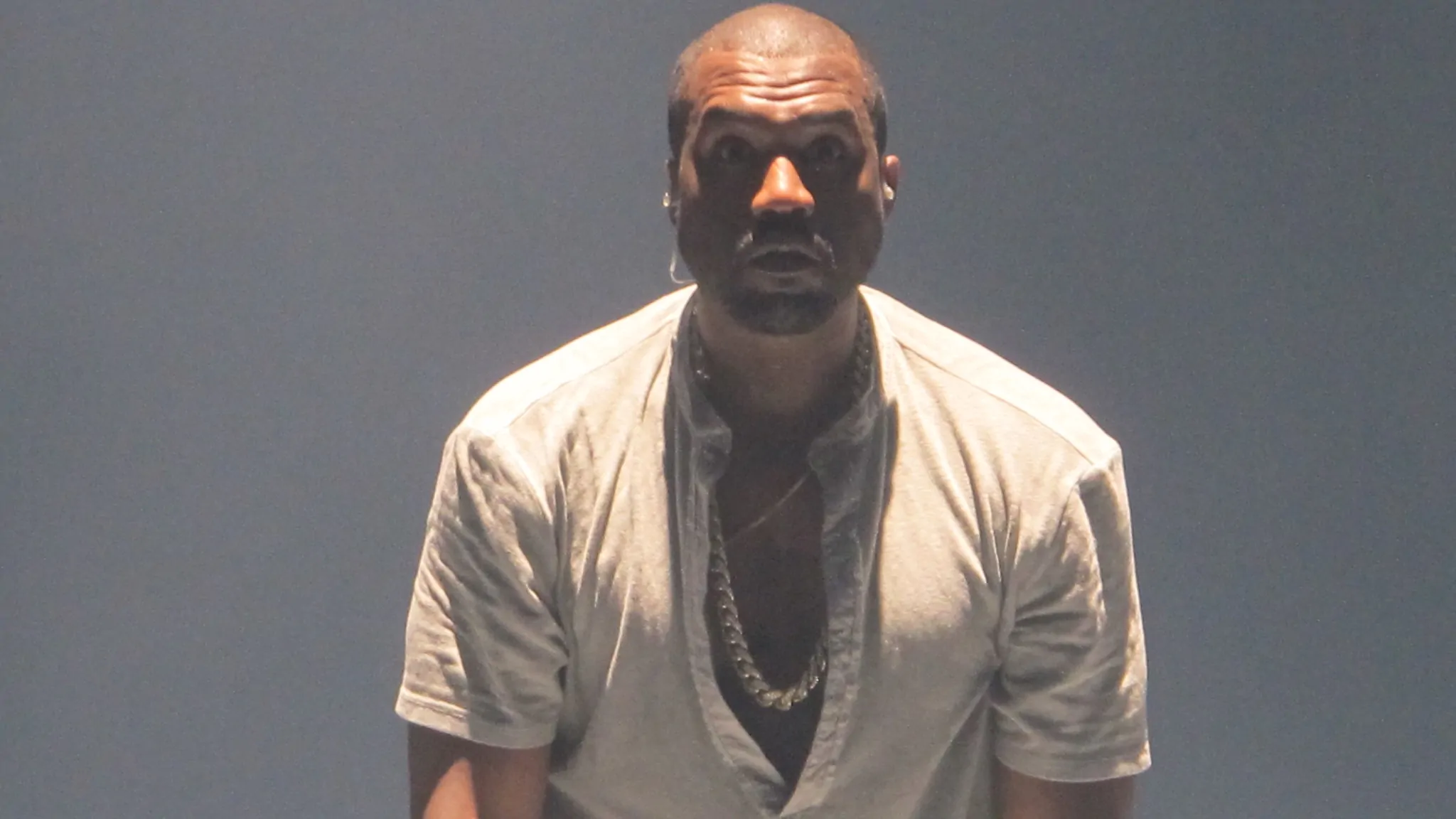

Kanye West is not a scholar.

Nor is he a philosopher, an intellectual or, as he called himself in 2013, a “creative genius.”

He is, though, a musician — a rapper, a lyricist, whatever you want to call him — and a successful one at that. And after a messy public outburst spread over multiple outlets over multiple days, he is most certainly an anti-Semitic bigot.

West’s latest spectacle began on Oct. 7 when he posted text messages originally sent to Sean “Diddy” Combs in which he said, “Ima use you as an example to show the Jewish people that told you to call me that no one can threaten or influence me. I told you this was war.” (That exchange was itself an attempt to hold West accountable for wearing a “White Lives Matter” during Paris Fashion Week.) In the late night hours that followed, West tweeted, “I’m a bit sleepy tonight but when I wake up I’m going death con 3 On JEWISH PEOPLE The funny thing is I actually can’t be Anti Semitic because black people are actually Jew also You guys have toyed with me and tried to black ball anyone whoever opposes your agenda.”

The tweet has since been deleted, but it stands together with clips axed from his recent Tucker Carlson interview that included riffs on Hanukkah and “financial engineering” and his belief that Planned Parenthood was created to “control the Jew population.” While white supremacists seem to be quite happy with him, few people in public life have stepped up to defend West or his comments, and those who have, like Indiana’s attorney general, have stumbled after inevitably having to put some distance between themselves and an idiot who is no longer useful.

And why should anyone stick up for someone so clearly committed to espousing old, tired and bigoted ideas? Why defend those same ideas in the public square as simply “his right” to say them or, failing that, trot out some other warm and cherished chestnut of free speech wisdom?

We shouldn’t.

Yes, West is absolutely free to say those things, and this discussion would be entirely different had some arm of the state decided to arrest him for his threat to go “death con 3.” Because while the First Amendment guarantees freedom from (most) government consequences for speech, it does not provide for those same freedoms when it comes to society at large, meaning while the government may not arrest him for what he said, Twitter — as a private platform — is free to delete his tweet, limit the reach of his account or, as in the case of Donald Trump, kick him off the platform completely. Social media platforms are not bound by the terms of the First Amendment (no matter what the Fifth Circuit seems to think) because they have free speech rights and free association rights, too.

Members of the First Amendment fire brigade, though, are often quick to lament the societal consequences for speech; for example, the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression and its president, Greg Lukianoff, have long complained about “cancel culture,” the idea that the Internet and social media have made it easier for people to be chastised and hounded for “bad” or “wrong” ideas. But what of it? Society has always expressed its disapproval of minority viewpoints — be they “good” or “bad” — and speakers have been forced to stand by their speech in the grand marketplace of ideas. Just because a majority of buyers might not be interested doesn’t mean that somehow the marketplace is flawed and broken; that we should, by necessity, institute societal controls on what would be (in this analogy) product reviews.

A generation ago, Cincinnati Reds owner Marge Schott faced the wrath of “cancel culture” after repeatedly voicing various racist, homophobic and anti-Semitic thoughts. Like West, she was not particularly bright and relished in the freedom to say whatever popped into her tiny little mind, like when she said in 1992, “Hitler was good in the beginning, but he went too far” in an interview with the New York Times. For that and other offenses, including using racial slurs in reference to members of her own team, Schott was suspended for a year from the Reds’ day-to-day operations. That suspension — an aborted “cancelation” attempt, I suppose — wasn’t enough for Schott to learn that her bigotry/misunderstanding of history wasn’t welcome in MLB’s billion-dollar empire; only four years after initially stepping in it, she said in a 1996 ESPN interview, *again* regarding Hitler, “Everything you read, when he came in he was good. They built tremendous highways and got all the factories going. He went nuts, he went berserk. I think his own generals tried to kill him, didn’t they? Everybody knows he was good at the beginning but he just went too far.”

She was suspended once more — this time through the end of the 1998 season — but eventually sold the team. Yet despite her ignorance, despite her bigotry, despite her boorishness, she still had defenders in the press, with some playing whataboutism, while others rung their hands about property rights, “thought police” and “political correctness.”

“Nobody threatened to take away Ted Turner’s team when he dropped to all fours in the lobby of the L.A. Hilton and started barking like a dog at the 1976 winter meetings,” wrote Cleveland Plain Dealer columnist Bud Shaw.

Gay Nuhn of the Dayton Daily News wrote he “was not defending her” and that he disagreed with “almost everything she has said and done.” Yet the two sentences directly preceding that disavowal were, “What we have here is 1692 revisited. Marge Schott is an old, doddering woman whose ideas run contrary to the popular and politically correct beliefs of the times, so let’s hang her on Gallows Hill in Salem, Mass.”

Writers, even as they were incorrectly conflating the First Amendment with Schott’s removal from baseball, fixated on this idea of “political correctness” — almost like that particular phrase is as meaningless as the one in vogue now. “The real reason behind Schott’s troubles is that she’s not politically correct and displays her incorrectness for all to see,” wrote John Woolard of the Long Beach Press-Telegram. “Marge Schott says stupid, irrational, racist, hurtful things. She is, quite honestly, a nincompoop, a card-carrying simpleton who makes such idiotic statements as ‘Hitler was good at the beginning.’ She is an easy target, a classic example of how not to win friends and influence people in the 1990s.” Yet Woolard declared baseball’s owners were “acting like Nazis” when they removed Schott from their ranks.

Likewise, Walter M. Brasch, a former newspaper reporter and editor and then-professor of journalism, wrote in the Pittsburg Post-Gazette that the First Amendment should apply to baseball because it “willingly accepts extensive government assistance” and that to toss her from baseball was unpatriotic. “By silencing Marge Schott,” Brasch wrote, “the owners of Major League Baseball, as American as apple pie and hot dogs, have shown how little they respect the foundation that is America.”

Schott’s defenders of yesteryear should bear an extra measure of shame because she was so very bigoted and dim, but the point remains the same as it ever was: Words that defend unpopular speech from societal consequence are wasted characters, a misuse of an endless resource that fails to recognize that this is a nation of unlimited opinions and views. For one person to say you have “bad” thoughts is not a tragedy, just as it’s not unfortunate for a thousand to do the same.

So long as the mob is only a metaphorical one — and so long as it is not driven and motivated by the state — let it come.