During Supreme Court arguments on Tuesday, the court’s conservative justices seemed to be searching for ways in which the court could side with Alabama Republicans and their contested voting maps, with Justice Samuel Alito going so far as to reframe and narrow the state’s argument, while the court’s more liberal justices pounded away at the obvious violations of past precedent.

In the end, the justices left little indication of which way they’ll rule on a case that could all but end the 1965 Voting Rights Act and set voting rights back by decades.

“As we know, the Supreme Court over the course of the last several decades has issued a number of rulings that have made it more difficult for Black voters to bring these claims and to have their rights protected,” said Deuel Ross, lead counsel and director at the Legal Defense Fund. “But we feel confident that the facts here are so egregious in Alabama – the fact that it splits this Black community that has existed in the state for 200 years [but] has egregious conditions – a lack of working water, a lack of adequate sewage – all things that having more representation – responsive representation – would really help. We’re not looking for any kind of guarantee. What our clients are looking for is a fair chance, an equal chance.”

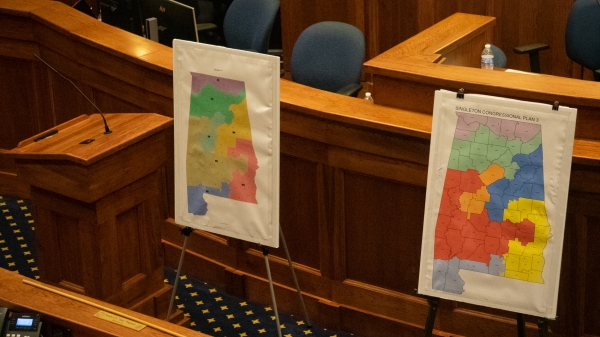

Currently, Alabama, which has a Black population of 27 percent and growing, has just one majority-minority congressional district out of seven. That’s a 14-percent representation rate.

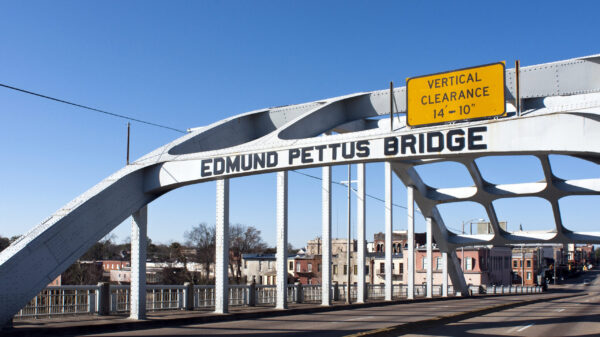

One of the key factors in that discrepancy – and one of the primary focal points between the attorneys and justices during arguments Tuesday – is the manner in which Alabama lawmakers divided up the Black Belt region of the state – an area that is predominantly Black and poor – while remaining protective of Mobile and Baldwin counties, along Alabama’s coast.

Dividing those two counties – in similar ways to how lawmakers divided up Montgomery and Jefferson counties – could lead to the creation of a second majority-minority district in the state.

Arguing for the state, Solicitor General Edmund Lacour said lawmakers followed a number of standard guidelines when drawing the new maps, including protecting “established communities.” Lacour maintained that the Mobile and Baldwin region was an established community that should not be separated, but couldn’t explain why it should be more protected than the Black Belt. With those parameters in place, however, Lacour said it was impossible to draw acceptable voting maps in Alabama, with “reasonably configured” districts, that included a second majority-minority district.

During another exchange, which drew national attention, Lacour, while arguing that the state was not purposefully discriminating based on race when drawing maps, said he believed it possible for the state to draw maps without a single minority district and still meet the requirements of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

Alito attempted to reel Lacour back in, calling some of his arguments “quite far-reaching,” and then providing him with a narrower, more focused argument. Alito suggested that he would “focus on whether the districts were reasonably configured.”

However, new Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson undercut Alito’s argument, noting that discriminatory results – and not simply disciminatory intent – were covered by the 14th amedment and that the framers never intended it to be “race neutral or race blind.”

Essentially, while providing historical context, Jackson showed that voting maps – no matter the intent – that result in under-representation of a minority group of people can be challenged.

Following the arguments it was unclear where the court stood. Aside from benign technical questions from Justices Roberts, Barrett and Kavanaugh, and absolutely nothing from Thomas and Gorsuch, the conservatives, who control the court, gave no indication of which way they might vote on the issue. However, should they reverse the appellate decision, which would have required the state to redraw the maps, it would be reversing a unanimous decision submitted by three federal judges, two of which were appointed by Donald Trump and approved by Republicans.