- Judge Dennis Challeen, who died in 2018, is known as the father of community-service sentencing.

The Minnesota judge, in 1972, did something extraordinary by sentencing non-violent offenders to community service.

At the time, Challeen’s actions were “widely criticized by those who favored punishment over restitution,” according to his obituary in the Nation Judicial College. Some 50 years after his bold move, the wisdom of his decision is widely accepted by most of the criminal justice system. Still, now as then, some favor punishment over restitution and rehabilitation.

Today, evidence-driven sentencing provides guides that address public safety through risk reduction and management of probation or community corrections eligible offenders.

Judge Challeen employed a less scientific approach to sentencing but one based on observation and experience.

He categorized offenders as either “NORPs,” “Slicks,” or “Slugs.”

NORPs, according to Challeen, were Normal Ordinary Responsible People who had acted out of character and could be expected to change their ways no matter what sentence they received — prison time, fine, or community service.

Slicks, he wrote, are perpetual victimizers who considered themselves more intelligent than everyone around them. They would never reform, so they needed to be incarcerated for as long as possible.

Slugs were weak people whose sentencing was a toss-up because if sentenced to live around bad people, they would also turn bad.

He also saw the conundrum the corrections system faced when incarcerating individuals.

In an untitled poem, he exposed the dilemma of incarceration.

We want them to have self-worth

So we destroy their self-worthWe want them to be responsible

So we take away all responsibilityWe want them to be positive and constructive

So we degrade them and make them uselessWe want them to be trustworthy

So we put them where there is no trustWe want them to quit exploiting us

So we put them where they exploit each otherWe want them to take control of their lives, own problems and quit being a parasite on us

So we make them totally dependent on usWe want them to be non-violent

So we put them where violence is all around themWe want them to be kind and loving people

So we subject them to hatred and crueltyWe want them to quit being the tough guy

So we put them where the tough guy is respectedWe want them to quit hanging around losers.

So we put all the losers in the state under one roof

With a few short verses, Judge Challeen shows the quandary inherent in the complexities of crime and punishment.

Alabama is building new prisons, but that is only one long-needed fix to the state criminal justice system.

Reform is often a dirty word in politics, even reforms that might lead to better public safety in the long run.

Unfortunately, most politicians see only as far as the next election and are hesitant or unwilling to back bold change.

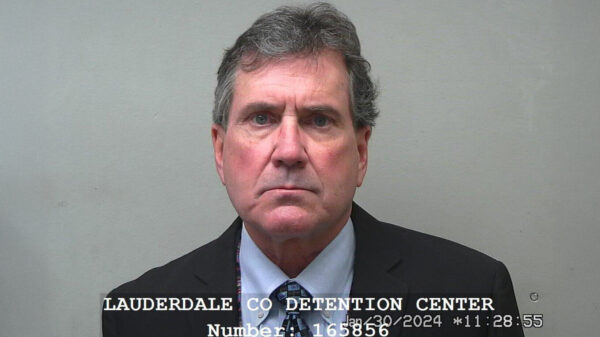

Even now, the state’s parole board is held hostage by the alleged crimes of Jimmy O’Neal Spencer, who is charged with murdering three people while on parole after being released under the state’s good time provision.

Public and political outrage over the killings has resulted in a drastic reduction in paroles for incarcerated individuals.

Attorney General Steve Marshall further politicizes the situation by claiming that Spencer should not have been given parole while criticizing the state’s good time law allowing for early release.

Spencer, whose life has all the markings of a career criminal, was released in December 2017, to a state-run facility and then to a halfway house. He gained full release on Jan. 12, 2018.

He was charged with capital murder on July 13, 2018, for the deaths of Martha Dell Reliford, 65, Marie Kitchens Martin, 74, and Martin’s great-grandson, Colton Ryan Lee, 7.

But something happened before the murders occurred that he was accused of committing that should have landed Spencer back in jail.

A month earlier, on June 15, 2018, Spencer was arrested in Boaz for possessing drug paraphernalia, resisting arrest and attempting to elude a police officer. His bond was set at $3,000 and he was released.

Why wasn’t his parole revoked?

Where was the Marshall County District Attorney?

And where was Steve Marshall then?

It wasn’t the good time law but the failure of the system that let Spencer post bond in Boaz before he murdered three innocent human beings.

Politicians who see Spencer’s crimes as a way to promote their political careers shouldn’t be allowed to use him as a poster child to halt criminal justice reforms.

Alabama can remain tough on crime while also being smart about criminal justice.

Some individuals should never be let out of prison, some will benefit from alternative sentencing, and others need only community service to pay for wrongdoing.

Judge Challeen’s actions half a century ago may have seemed dangerous at the time or at least foolhardy, but today we mostly embrace his ideas.

Change, especially in public safety, should come slowly and methodically, but once in a while, we need a Judge Challeen to show us what is possible.