Maybe it was the sizzling Alabama heat that made them stupid.

Maybe they forgot how social media works.

Or maybe they’re just bad, racist people.

Whatever it was, three Tuscaloosa-area residents have found themselves in legal trouble over the last month stemming from two separate racist and threating videos posted to social media. Members of the community are rightly upset and perhaps scared since we’re less than two months removed from the shooting at a Buffalo, New York grocery store that was clearly motivated by the racist hatred of Black people. Yet these videos – and more specifically, the law enforcement and state-backed response to them – should give us pause as we consider exactly what the First Amendment protects and how it should be applied.

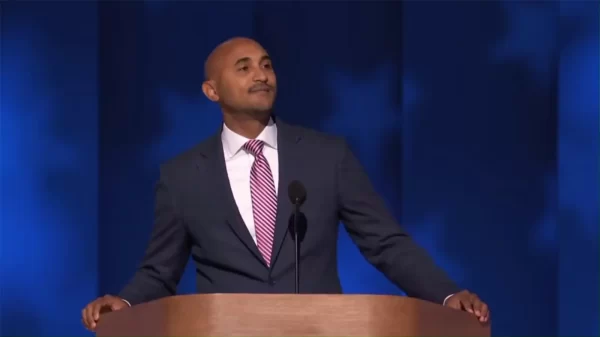

In connection with one racist video, Sydney Angela Holder and Emily Elizabeth Cornett were arrested, charged with disorderly conduct and expelled from Shelton State Community College in June after the Tuscaloosa Police Department and school administrators were made aware of a clip circulating on social media. In the 10-second video still available on Facebook, Cornett appears to be filming the pair while they’re in a Walmart, turning the camera to show Holder holding up her jeans, showing off her boots and boasting of her hidden pistol.

“Concealed carry, m**********r,” Holder says. “I’ll shoot a n****r in Walmart.”

The two 20-year-old (now former) nursing students laugh because it’s a joke, a cruel one in poor taste even before recent events. However, it is not a crime to be racist or astoundingly dense, and this video – despite its overt racism and reference to violence – is likely protected speech under the First Amendment, thereby rendering both the pair’s arrest and their expulsion from a state-run school unconstitutional.

For the state to criminally punish speech, it has to fall under one of the categories delineated by the Supreme Court, whether that’s obscenity, incitement, fighting words or true threats. The video isn’t sexualized speech (obscenity), nor is it a call to illegal action (incitement), nor is it language directly addressed to an individual that could reasonably cause them to react with violence (a fighting word). (As to the question of fighting words, there is no one else aside from Holder and Cornett in the video as they are talking only to the camera.)

Therefore, we’re left with the question of whether the video represents a “true” threat, a legal doctrine the Supreme Court has not been great at defining but ultimately boils down to whether the speech in question is capable of being reasonably interpreted as a serious intention to commit harm. In 1969’s Watts v. U.S. – the Supreme Court’s first case on true threats – the Court made it clear that the context in which the possibly threatening statements were made are critical in determining whether they’re protected speech. For that defendant, his “threat” of “if they ever make me carry a rifle the first man I want to get in my sights is L.B.J.” was not enough to support a criminal conviction because it was conditional (“*if* they give me a gun”) and because it was a statement made at a political protest. Thus, the context made it clear to listeners that it was a form of violent rhetoric expressing opposition to the government and not a sincere expression of a desire to harm President Lyndon Johnson.

In this video, the context is mostly clear — Holder and Cornett are laughing because there are apparently few things funnier to them than racial slurs and exercising the right to carry a presumably loaded firearm in public. To them, it is a joke, and for most other decent people, it’s offensive. But that offensiveness does not transform it into a criminal act. Because of their cruel smiles, their casual indifference, their lack of an unconditional statement of intent (something to the effect of “I will shoot the next [racial slur] I see in this Walmart”), the video is both a crass demonstration of racism and speech protected by the First Amendment.

The only thing that could change this conclusion is if there’s something that alters the context of what we see, such as Holder or Cornett sharing the video in a way that no longer makes it a joke (i.e. posting to a Black person’s social media page with the ominous caution to “watch out” when they go to Walmart). The fact they’re only charged with misdemeanor disorderly conduct likely speaks to the idea that this more serious context is missing, but the lesser charge doesn’t negate the unconstitutionality of their arrests – and their expulsion from Shelton State only compounds it.

The second video, which resulted in the arrest of a Tuscaloosa County juvenile on July 1, is a more complicated case because not only is the video no longer publicly available, but the clip that was originally posted was heavily edited, thereby removing much of the context that is necessary to make an accurate true threats determination. According to a report by the Tuscaloosa Thread, in this video, which was produced and edited by an online content creator, an internet streamer was placed into a video chat conversation on the Omegle platform with the juvenile in question, who says he’s from Northport.

At some point during their conversation, the juvenile says, “I’m gonna shoot up a school and kill all the Black children inside, watching their brains explode from the inside.”

The streamer says that’s nothing to joke about in response.

And that’s all the public knows about the video.

In many ways, the situation is strikingly similar to N.C. v. State, a 2020 decision from the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals that I’ve already written about. They both involve juveniles making culturally inappropriate references to school shootings to out-of-state recipients via the internet. But there are important differences – the communication in N.C. was neither racist nor so specific (in that case, the defendant simply shared a meme of the Columbine shooters) and we have a sense of the context in that case because the trial court record shows the defendant immediately recognized his joke was in poor taste and apologized. That apology, when coupled with the fact he was speaking with someone in Georgia and evidenced no intent to scare students in that district or his home one here in Alabama, meant his juvenile adjudication on a charge of making terroristic threats could not stand.

We don’t know the Tuscaloosa County student’s reaction to the real-time feedback he got in response to his violent speech. After his Omegle chat partner told him a racially motivated school shooting was not the sort of thing to joke about, what was his reaction? Was there a moment of self-realization? Did he attempt to take back his statement? Or did he lean into it? Did he say to this internet stranger something like, “I don’t care what you think, and I hope you tell everyone in Northport about what I said”?

There are few, if any, things that Americans are not legally allowed to say under all circumstances and situations, and context is critical in determining whether something is simply offensive or if it is legally punishable. The video of the Shelton State students is clear on its face, whereas the Tuscaloosa County juvenile’s statement lacks the publicly known surrounding material that would enable us to reach a similar conclusion.

The American Democratic experiment is constrained by rules, one of those being that the government can’t punish speech it simply finds to be distasteful. But society, individuals, people who are upset and angry – they’re not bound by that same rule. Reconciling those two ideas is difficult, especially when we see people engaging in speech that we want sanctioned.

Yet that’s the burden of the First Amendment and the cost of living in a free society.