A brief filed this week with the the U.S. Supreme Court in the ongoing legal battle over Alabama’s new Congressional district lines argues that the lower court was correct when it found the lines disenfranchise Black voters.

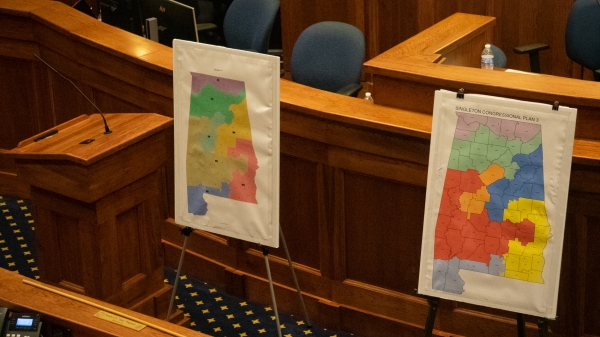

The lower court determined that the new district lines do not comply with the Voting Rights Act and ordered the state to remedy the lines by creating a second majority-minority district before the 2022 elections.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in and issued an injunction allowing the maps to remain in place while the issue is fought in the nation’s highest court.

The group of plaintiffs, led by the NAACP argue in the brief that the substitute plan with a second majority-minority district is viable and shows how the state ran afoul of the Voting Rights Act.

“Defendants do not, and cannot, show clear error in the court’s findings that the Plaintiffs’ illustrative plans comply with traditional districting criteria as well as or better than HB1, and that race did not predominate in those plans,” the brief states. “Instead, Defendants argue that race should play no role whatsoever in meeting the threshold evidentiary requirement in Thornburg v. Gingles. But Gingles expressly requires a showing that an additional majority-minority district can be drawn.”

The plaintiffs argue that the court did not force the state to follow their exact substitute plans as submitted.

“Indeed, the court did not order Alabama to enact Plaintiffs’ plans or even to create a second majority-Black district. Rather, it afforded Alabama the opportunity to devise any remedy that would, for the first time, provide Black Alabamians an equal opportunity to elect their preferred candidates in a second congressional district.”

The brief looks back at Alabama’s history of discriminating against Black voters when drawing district lines for more than 50 years.

“This discrimination extended to congressional plans. Since 1875, Alabama has cracked the Black Belt across four or more districts. From 1875 to 1917 and 1933 to 1970, Ala-

bama separated Mobile and Baldwin counties. The 1950 map placed Mobile with six Black Belt counties in District 1, separating Mobile from Baldwin. By 1960, District 1 had a “substantial” (about 39 percent) Black population.

“In 1960, however, rather than redistrict after losing a representative in reapportionment, Alabama elected all representatives at-large statewide. For the 1962 at-large elections, a prominent politician pushed the Legislature to add anti-single shot voting rules to prevent the election of “a scallowag or a Negro” to Congress and, ultimately, the Alabama Supreme Court imposed anti-single shot rules.”

The brief argues the new 2021 map, drafted by Randy Hinaman, fail to account for a decrease in the white population in Alabama from 1990 to 2020.

“From 1990 to 2020, Alabama’s White total population fell from 73.6 percent to 63.12 percent, while the Black total population increased from 25.26 percent to 27.1 percent. Yet Hinaman preserved the prior racial balance in each district, including the majority-Black District 7, in HB1. Neither the Legislature nor Hinaman analyzed racial voting patterns to assess whether District 7’s high level of (Black voting age percentage) was necessary in 2021 to elect a Black-preferred candidate, nor did they examine whether two compact majority-Black or ‘crossover’ districts (i.e., majority-White districts where Black-preferred candidates can win) could be drawn.”

In addition to arguing the merits of the case, the brief also argues that the lower court did not clearly err in its initial decision.