All families have their stories. The ones rarely spoken, nearly forgotten.

Black families definitely have some, particularly from the days when lynchings were commonplace.

My mother’s baby brother Omega, the last of 14, told me these two.

My grandfather, Bead Lloyd Stephens, almost was lynched. This happened in the late 1930s or early ’40s. He would have been in his late 40s or early 50s.

Grandpa was a World War I veteran, farmer and landowner. He and my grandma Odessa lived in the rural Poplar Springs community of Marianna, Fla. They were well on their way to the 14 total births by then.

Of course, the richness of their family didn’t matter. Not back then. Not to most white folks. And not to the ones who wanted to kill Grandpa.

Typical story: Grandpa had an encounter with a white man who felt disrespected. White man left the scene and eventually returned with a gun-wielding posse.

What he didn’t know was that my grandfather had anticipated this.

Of course, he did. Call it common sense. Survival instinct. Blacks knew the protocol of the times.

Whites were quick to conjure up a lynching in those days. So,most blacks had been conditioned to account for the immediate danger posed by white supremacy. Step off the sidewalks to let whites pass. Never look them directly in the eyes when speaking to them or being spoken to by them.

And always use the required honorifics. “Sir.” “Ma’am.”“Boss.”

Whatever Grandpa did or didn’t do was his death sentence. But when the whites came gunning for him, they encountered a roadblock. Grandpa, his brothers and my older uncles were strapped and waiting on them.

The lynching became a shoot-out. Outgunned and overwhelmed, the whites retreated. They never bothered Grandpa again.

Bead Stephens lived another two-plus decades in peace, dying in 1967 at the age of 79.

My family isn’t the only one with a lynching story. Other black families do too: actual lynchings, attempted lynchings.

The threat of a lynching. Our family has one of those stories, too.

My Uncle Clifford Stephens, known to me as Uncle Mop, was the target. The threat came when he was still living in Marianna.

It came from a cop. Because of a woman.

Uncle Mop had to leave town or else he would be a dead man. He escaped to Dothan, Ala., just a few miles north of the state line. He changed his name to Ralph Malone and built a new life.

In my sole memory of Mop, he is walking down one of black Marianna’s dusty, unpaved streets, a few years after he was forced to leave. It was night. He was headed back to Dothan.

He stopped under an orange streetlight, turned back toward us and waved good-bye. Mop was tall, maybe six feet, two inches, with a wiry Afro, big ears and a big smile to match.

I’d never see him again. A man who had to sneak into his own hometown to stay alive.

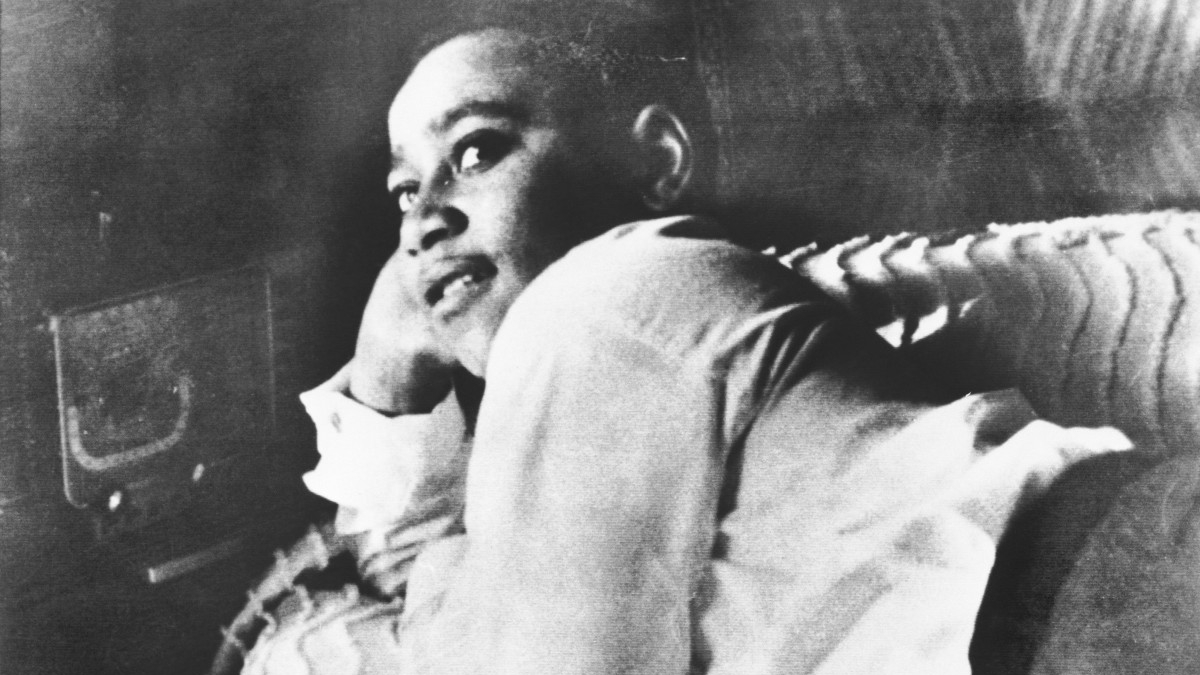

Very soon, maybe in the next two weeks, President Biden will be signing the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act of 2022. It will be our nation’s definitive statement against this form of violent racial terror. Anyone convicted of a lynching will be sent to prison for 30 years.

Racial lynchings were common before 14-year-old Emmett Till was murdered in Mississippi in 1955. The Equal Justice Initiative estimates that more than 6,000 took place between the end of the Civil War in 1865 to 1950.

At many of these macabre events, hundreds or even thousands of whites would gather to see mutilated black bodies swinging from trees. Sometimes, postcards memorialized these gatherings. Others were small, private affairs. Till’s was one of those.

Either way, the message was clear. Challenging white supremacy – or appearing to do so – was a death sentence.

That demon still hasn’t been exorcised from America’s soul. Ask the families of Ahmaud Arbury, Walter Scott, Laquan McDonald, George Floyd and more than a few others.

So when Biden signs the bill, my thoughts will be with those families and with my own. The victims and almost victims – and we who love them.