“Hit the water!” Those were the last words Willie Edwards Jr. heard. Facing the barrel of a gun, 24-year old Edwards jumped from the Tyler-Goodwyn bridge.

The four klansmen who forced Edwards off the bridge and watched him descend 40 feet below into the Alabama River in the early morning hours of Jan. 23, 1957, likely thought that they’d face no consequences.

Montgomery Police and FBI agents did little to investigate, even after local fishermen found Edwards’ body in the Alabama River three months later.

Over the next 50 years, county, state and federal officials reviewed the case. Prosecutors attempted several times to bring Edwards’ killers to justice.

The four klansmen responsible for Edwards’ death would confess, recant, and pass and fail polygraphs. Witnesses would testify, change their testimony and refuse to testify at court hearings.

Ultimately, the four klansmen were never be convicted for the murder.

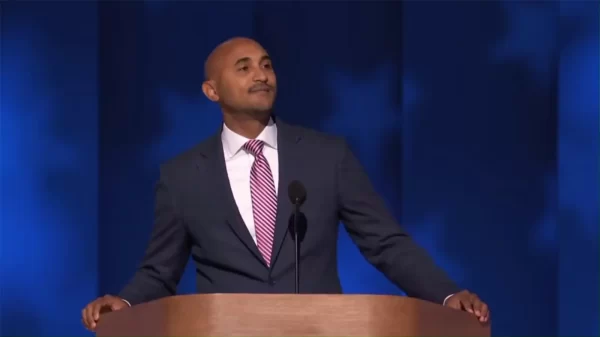

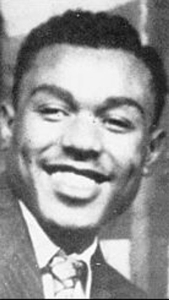

Willie Edwards, Jr., father of three children who was murdered by klansmen in Montgomery, Alabama on January 23, 1957 while on the job as a truck driver for Winn-Dixie. (Courtesy of Malinda Edwards)

Edwards’ daughter, Malinda Edwards —who has made it a mission to keep her father’s memory alive, especially on his birthday, Nov. 22, and the anniversary of his disappearance, Jan. 23 — said that she believes that there was a consequence for the Klan members who killed her father. “They had to hear his name every year for the rest of their lives,” she said in a telephone interview.

Found in the Alabama River

Willie Edwards Jr. lived in Hope Hull, Alabama, a rural community on the outskirts of Montgomery with his high-school sweetheart Sarah and two young daughters, Malinda and Mildred. Sarah was pregnant with their son.

Edwards drove a truck for Winn-Dixie, a grocery store chain. He’d agreed to work an extra evening shift for another Winn-Dixie truck driver who’d called in sick the day he went missing.

While he was on that shift, taking a break, klansmen took Edwards from his truck and drove him to the Tyler-Goodwyn Bridge.

After Edwards refused to agree that he’d done something to offend a white woman, one of the men pointed a gun at Edwards and told him to “hit the water.”

With what seemed to be a no-win situation, Edwards climbed up the railing and jumped. He may have thought he could make it, as he had swum in the Alabama River all his life.

That night, Sarah went to sleep, not knowing why her husband wasn’t at home yet.

Sarah Edwards Salter, who was married to Willie Edwards, Jr. when he went missing in 1957. (Courtesy of Malinda Edwards)

The next morning, Sarah told her father-in-law, Willie Edwards Sr., who began a search. Edwards Sr. found the Winn-Dixie truck that his son had been driving in a parking lot in A&H’s grocery store on Lower Wetumpka Road.

Edwards Sr. saw signs of foul play. He noticed that the truck’s lights were still on, the driver’s door was ajar, and his son’s wallet and some food were left on the passenger seat, according to a statement he made to investigators years later.

He went to the Montgomery Police, pleading for them to investigate.

Their investigation was half-baked at best. They interviewed a Winn-Dixie dispatcher who confirmed Edwards’ disappearance and searched the woods near where Edwards’ truck was found, according to police records, which listed Edwards’ case as one of a missing person.

“The police knew what happened. They were in the klan. They were never going to look for him,” Edwards’ daughter, Malinda, said. “The police told my mom that he left her.”

Edwards’ family continued to look for him and, after two months, contacted the FBI, who told the family that they lacked investigative jurisdiction, according to a Justice Department memo. Instead, they posted a missing person report on April 8, 1957.

Exactly three months after Edwards’ fatal jump, despite law enforcement’s obfuscation, his family’s suspicions were confirmed. Fishermen discovered his body on April 23 in the Alabama River, ten miles west of Montgomery, where the current had drug him. Edwards drowned after landing in the water. Despite the evidence, the coroner listed the cause of death as unknown and law enforcement’s dereliction continued.

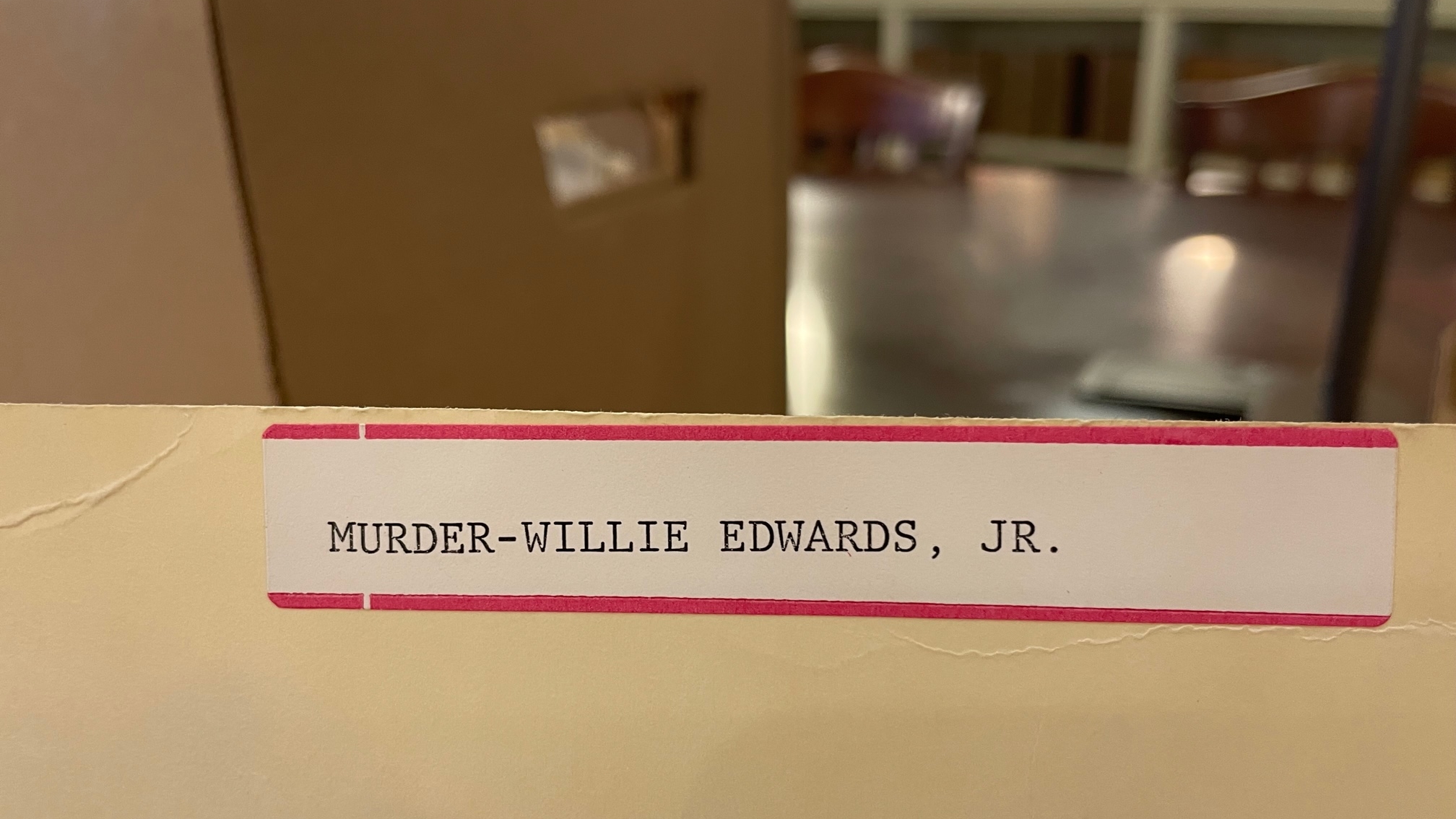

Although an April 23 police report shows a notation added to the case file — “Murder (pending)” — Montgomery police took no further action.

Sarah was left to raise her two toddlers and week-old infant son without assistance or compensation from her husband’s employer, Winn-Dixie.

A Klan wrecking crew

There were four klansmen at the Tyler-Goodwyn bridge on the night of January 23, 1957.

“Sonny” Kyle Montgomery, 18; Raymond C. Britt, 18; Henry Alexander, 28; and Jimmy D. York, 52, were members of a Montgomery wrecking crew in the United Klans of America, an organization headquartered in Tuscaloosa.

Livingston was a klan leader, who had been intimately involved in all of the Montgomery Klan’s activities, and also had many friends in the Montgomery Police Department, according to The Klan by Patsy Sims.

A month after Edwards’ body was discovered, two of the men, Livingston and Britt, went on trial for bombing a church in January 1957.

Although they both confessed, an all-white, all-male jury acquitted them. Spectators in the courtroom cheered after hearing the verdict, according to news reports at the time.

“Even if somebody was arrested and went to trial, it was very, very rare that a white jury would convict a white person for anything against a black person,” said journalist and author Stanley Nelson, who has written two books about klan murders and helps lead Louisiana State University’s Cold Case Project, in an interview at a local coffee shop in February 2022.

Livingston and Britt were charged in other bombings. The other two men, York and Alexander, also faced charges in connection with the January 1957 bombings.

The state dropped all the charges against the four men at the end of the year.

In the following years, Livingston continued to escape prosecutions for crimes he was involved in. One of his unpunished crimes was famously captured by an Alabama civil rights photographer moments before Livingston swung a baseball bat at a Black woman attending a demonstration on Feb. 27, 1960, on Dexter Avenue to protest segregated lunch counters in downtown Montgomery.

‘They wouldn’t let it go’

In 1970, Alabamians elected the nation’s youngest state attorney general, William Baxley of Dothan who began investigating a more than a decade-old cold case, the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, where four young Black girls were murdered.

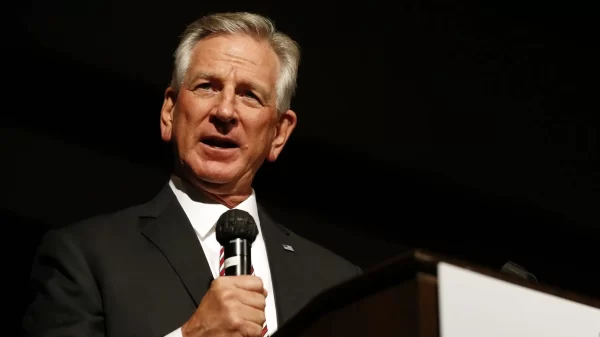

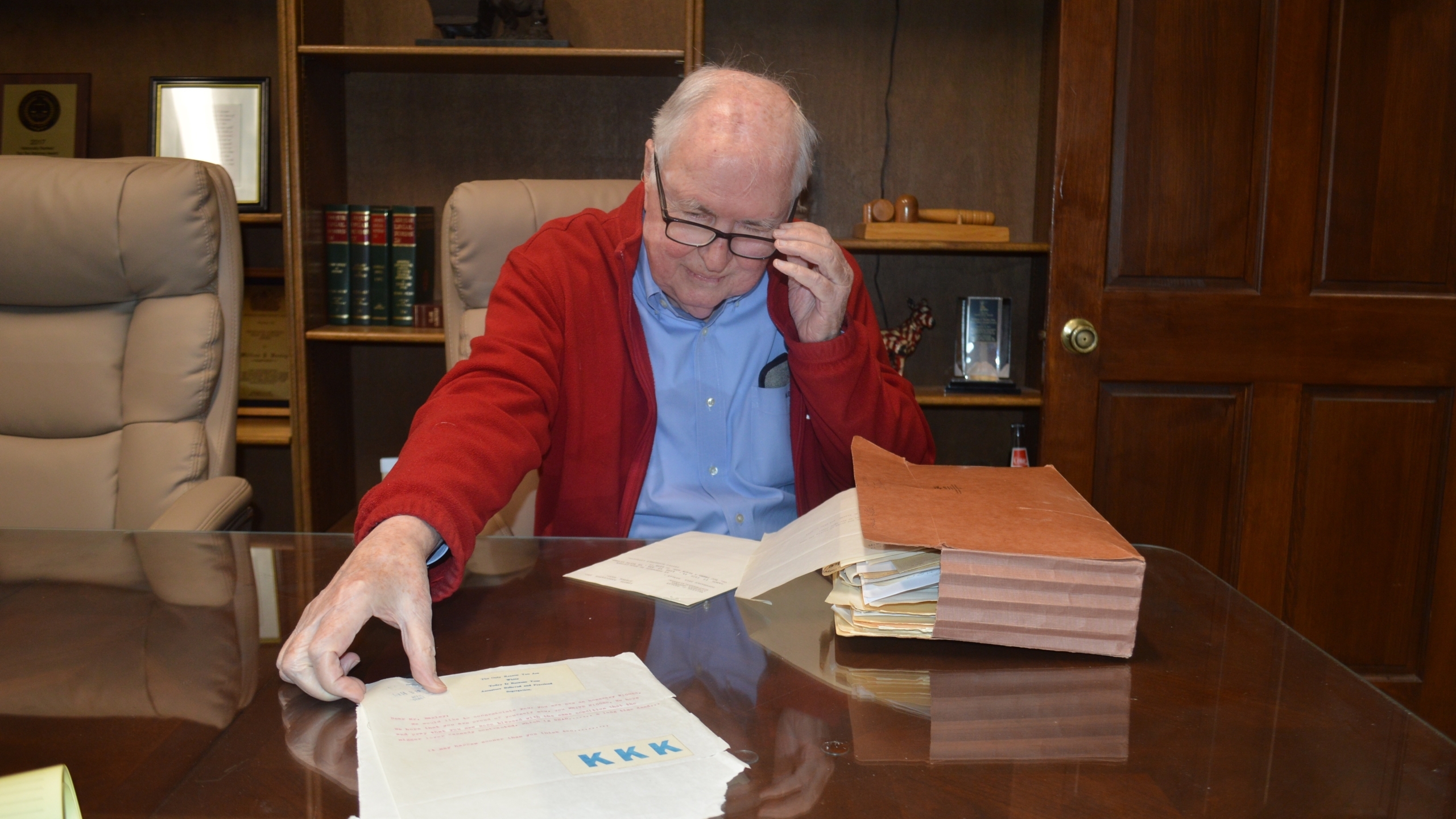

In a March 2022 interview at his law offices, Baxley recalled receiving numerous threatening letters for reopening the case, one of which he notoriously responded to with the words “kiss my ass” in a letter.

“Most of the letters came from out of state,” said Baxley.

William Baxley, former Alabama Attorney General, with some of his files at his law offices. (LIZ RYAN/SPECIAL TO APR)

At the end of 1975, one of Baxley’s staff investigating the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, former Montgomery Police Officer Tom Ward, was at the police administration building when he spotted “Sonny” Kyle Livingston.

Ward knew Livingston as he’d investigated him 20 years earlier for the January 1957 bombings in Montgomery and asked Livingston about his involvement with the klan.

Livingston told Ward that he wasn’t involved in the 1963 bombing because he’d gotten out of the klan after a 1957 incident where he and other klansmen had forced a Black man to jump from a bridge, a confession that Livingston later denied making.

Ward shared his taped conversation with another retired police officer, Jack Shows, who was also working for Baxley.

Shows and Ward began to suspect that the same four-man klan wrecking crew they’d investigated two decades earlier for the January 1957 bombings was involved in this crime.

Throughout January 1976, Shows and Ward sought out the four klansmen as well as other witnesses, according to the attorney general files in the Alabama Department of History and Archives.

Shows and Ward spoke with Livingston again and arranged a meeting in their offices. Livingston never showed up.

Alexander’s wife told Shows and Ward that her husband was involved in the crime. She also confirmed that he was an informant for the FBI, according to the attorney general’s files at the Alabama Department of History and Archives.

Jimmy York met with investigators at his home. Having just survived a stroke, York told investigators that he was not able to recall any details or his involvement in the crime.

However, when he left the room, his wife told Shows and Ward that she believed that Alexander had threatened her husband.

When he returned to the room, investigators asked York about Alexander’s threat and concluded that York was actually more afraid of Livingston. Alexander told them that Livingston should not be on the streets.

Baxley recalls that Shows and Ward’s intuition and doggedness pieced together the details of the crime.

“They wouldn’t let it go,” said Baxley. “They just kept digging.”

A grand jury indictment

Within six weeks of Livingston’s revelation, Baxley was near to indictments of the klansmen.

In a murder case with no witnesses at the scene other than the four suspects, prosecutors would have to get one of the klansmen to flip on the others.

“We decided, of the four, that Britt was probably the one most likely to break,” Baxley said. “We brought Britt in by subpoena to the office and leaned on him hard.”

Within an hour, Britt confessed. In exchange, Baxley gave him immunity from prosecution.

After Britt signed the affidavit on Feb. 20, 1976, Baxley ordered the arrests of Livingston, Alexander and York, and charged all three with first-degree murder and second-degree manslaugther.

Prosecutors argued to keep Livingston in jail as they believed he was dangerous and had threatened one of the investigators, but a judge released all three men on bond.

Baxley’s star witness, Britt, testified at a Feb. 27 preliminary hearing and told Baxley that he feared retaliation from the other three, especially Livingston. Baxley agreed to provide a plainclothes security detail.

A week later, a grand jury indicted Livingston, Alexander and York.

A few weeks later, Judge Frank B. Embry heard the case at a preliminary hearing where the three defendants pleaded not guilty.

At 83, Embry, who had been a judge for more than 60 years and was retired, served as a supernumerary judge assigned by the Alabama Supreme Court to Montgomery County to hear this case.

In a surprise move, Embry dismissed the case.

Embry’s decision was based on the fact that prosecutors had not provided a specific cause of death, something that Baxley believed could be proven at trial.

“Judges don’t usually throw out indictments,” said University of Alabama law professor Russell Gold in a telephone interview. “It sounds aberrational that the judge threw it out.”

Baxley filed a motion to the judge to hear the case again, which the judge agreed to.

However, Embry again denied Baxley’s motion to indict the defendants.

“If we’d had a trial, we would have had a good chance of getting convictions,” Baxley said.

Witnesses refuse to testify

While Alabama law at that time did not allow for state prosecutors to appeal the judge’s decision, Baxley considered attempting another legal challenge to reindict the defendants, but he subsequently encountered problems with the witnesses.

In June, Baxley’s star witness, Raymond Britt, changed his previous confession: Livingston wasn’t at the Tyler-Goodwyn bridge as he had previously stated. He failed a polygraph test about his previous statement, which prosecutors would have to report to the court.

Britt’s recanting destroyed his credibility as a witness.

Then Alexander’s wife changed her statement and refused to testify.

“The number one thing I see in these cases is fear of witnesses to testify for fear of their lives,” Nelson said. “They also may be sympathetic to the klan.”

Further complicating any attempt to reindict the defendants was a polygraph agreement that Baxley had made with Livingston’s lawyer. Baxley would allow the results of a polygraph to be used in court, as he’d thought that Livingston would fail the polygraph.

To Baxley’s surprise, Livingston passed a polygraph test.

Baxley insisted on a second polygraph test and personally attended to observe the results.

Livingston passed the second polygraph test, too.

That meant that in any future prosecution, Baxley would have to present the fact that Livingston passed two polygraph tests stating that he was not at the scene of the crime.

“Some people can lie and pass a polygraph. And some people can fail a polygraph repeatedly and still be telling the truth because they don’t do well under the pressure,” Nelson said.

By today’s standards, polygraph tests are viewed as unreliable.

The final blow was when an FBI agent approached Baxley with a message to go easy on Alexander as he was one of the FBI’s best informants.

Baxley can’t recall the name of the FBI agent and said that this was the only time in his career that he was ever approached by the FBI in this manner.

At that point, it was not feasible for Baxley to make another go at indicting the suspects.

“Justice was not served,” Baxley said.

Still, Edwards’ family recognized the attempt by Baxley to bring Edwards’ killers to justice.

“I’ll be forever grateful to him for what he did,” Malinda, Edwards’ daughter, said.

Montgomery District Attorney Ellen Brooks reopens the case

Edwards’ daughter Malinda wrote to Montgomery County’s District Attorney Ellen Brooks on May 22, 1997, about the case and the two met in July in Montgomery.

Brooks agreed to reopen the case.

Her first action was to secure a new autopsy to see if a cause of death could be determined.

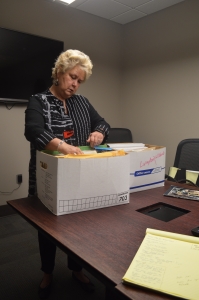

Ellen Brooks, former Montgomery County District Attorney, with the Edwards case files at the DA’s office. (LIZ RYAN/SPECIAL TO APR)

Brooks arranged to exhume Edwards’ body for a second autopsy, coordinating with Lowndes County officials — the cemetery where Edwards’ was buried — the sheriff’s offices and the coroner.

Coroner Dr. James Lauridson and forensics expert Dr. Michael Baden determined that Edwards had drowned in the Alabama River and that his death was a homicide.

Brooks petitioned state officials to update the death certificate. Edwards did not die by accident or suicide; it was a homicide.

“[The autopsy] told the truth for the first time,” Brooks said.

Next, Brooks and her team researched every available record to identify people still living that they could interview.

“What we did was we went back and tried to reconstruct everything,” Brooks said. “Time is the biggest problem with memories, deaths, and evidence.”

Of the four original suspects, two were dead. York died in 1979. Alexander died in 1992 after confessing to his wife about his involvement, according to a letter she wrote to Mrs. Edwards.

Two suspects were still alive at the time: Britt, who had turned state’s witness and then recanted his testimony, and Livingston, who first told investigators 20 years before he was involved and then subsequently denied his involvement.

In an interview in the Montgomery County District Attorney’s Office in March 2022, Brooks recalled Livingston.

“I personally knew who Sonny Kyle Livingston was, because he owned a bail bond company and he had a very well-known reputation for being a klansman,” Brooks said. “He had been prosecuted by this office for klan related activity.”

After a nearly two-year investigation, Brooks was ready to bring the case to a preliminary hearing.

Brooks believed that Livingston was involved in Edwards’ murder.

“He was not only a member of the klan, but a leader, and was known to organize things and certainly was no stranger to violence,” she said.

It was also clear to Brooks that the klansmen planned the crime in advance.

“The fact that they knew where to find Mr. Edwards and they were not looking for him, the fact that they had a car and a place for him to sit, that they took him to a destination that was obviously pre-chosen,” Brooks said.

At the preliminary hearing, Brooks requested Britt testify. Britt had moved to Mississippi and refused to return to Alabama. Brooks asked Alexander’s wife to provide a statement for the hearing. When she refused, Brooks called her as a witness. She pleaded the fifth amendment and would not speak about her ex-husband’s involvement in the crime. Without Britt and Alexander’s wife’s testimonies, Brooks knew it would be an uphill battle with a grand jury.

Grand jury says klansmen were responsible but indicts no one

At the grand jury, seven people testified and the DA’s office provided 36 exhibits. There is no public record of the special grand jury’s deliberations as Alabama law requires grand jury records to be sealed.

For the first time in this case, a grand jury reported that klansmen and their associates were responsible for the murder of Willie Edwards Jr.

But the grand jury did not indict any specific individuals.

“No true bill returned because of the death of some suspects and because of insufficient evidence due to the 1976 immunity and polygraph agreements with some suspects,” stated the grand jury’s report.

Montgomery County prosecutors believe that they did what they could with the evidence and the witnesses that were still alive 40 years after the crime.

“I was convinced that we had done everything humanly possible,” Brooks said in a March 2022 interview.

50 years after first looking at the case, the FBI reopens the case

Fifty years after the FBI determined that Edwards’ case was solely a missing person’s case, the FBI reopened it along with more than a dozen other Civil Rights Era cold cases in Alabama under the Emmett Till Act of 2007.

On June 9, 2011, FBI agents interviewed a suspect, who told them he didn’t remember confessing to involvement with Edwards’ death.

While the name of the suspect is redacted in the Department of Justice memo, “Sonny” Kyle Livingston was the only one of the four suspects still living at the time.

The FBI took no further action and closed the case.

“The justice system failed him,” said Tafeni English, a native Alabamian and director of the Civil Rights Memorial at the Southern Poverty Law Center in a March 2022 interview at SPLC offices in Montgomery. “When it comes to black people, how easy it was to close the case,” she said.

Willie Edwards Jr.’s legacy

The Tyler-Goodwyn bridge that klansmen forced Edwards to jump off is gone, demolished in 1980.

“When it was torn down, it still didn’t erase the memory of what happened,” Brooks said.

Malinda Edwards, daughter of Willie Edwards, Jr. (Courtesy of Malinda Edwards)

In Alabama, Willie Edwards Jr. is remembered.

The Southern Poverty Law Center included Edwards’ story in their Free At Last book and recognized him along with 39 other individuals in their civil rights martyrs memorial in Montgomery.

“Edwards’ case shows how families have to fight for justice,” said English. “There was no accountability.”

Edwards’ story has been told to University of Alabama Honors College students by Professor Billy Field.

Growing up in Sylacauga where Edwards drove on his last shift for Winn-Dixie, Field was personally moved by Edwards’ story.

“This is a story that deserves to be told,” said Field, who remembers from his childhood seeing the “Welcome to Sylacauga: Home of the Ku Klux Klan” sign.

Field, who has made films in Hollywood, is working on a film with students about Edwards’ story.

And Edwards’ daughter Malinda regularly talks to church groups, employers and university classes, among others, that want to learn more about her father and what happened to him.

“He’s always going to be that cry for change and justice,” Malinda said.