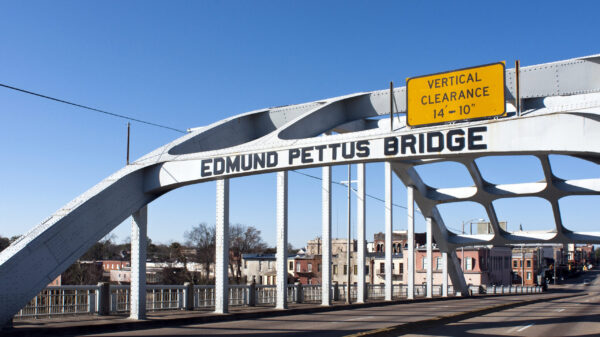

U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris stood on the “hallowed ground” of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on Saturday and juxtaposed the 1965 fight for voters rights with laws she said are suppressing those rights today.

Harris said the men and women who marched across the bridge in 1965, met with violence by law enforcement, “were marching for the most fundamental right of American citizenship: the right to vote.”

“Today, we stand on this bridge at a different time,” Harris told hundreds of citizens gathered to join her in the annual march across the bridge. “We again, however, find ourselves caught in between. Between injustice and justice. Between disappointment and determination. Still in a fight to form a more perfect union. And nowhere is that more clear than when it comes to the ongoing fight to secure the freedom to vote.”

Recent laws passed by several state legislatures are a direct response to the turnout, Harris told the crowd.

“A record number of people cast their ballots in the 2020 elections,” Harris said. “It was a triumph of democracy in many ways. But not everyone saw it that way. Some saw it as a threat.”

Harris encouraged those in attendance to keep fighting to ensure voting rights are protected.

“If we all continue to work together, to march together, to fight together, we will secure the freedom to vote,” Harris said.

Joining Harris were Deputy Secretary of Veterans Affairs Donald Remy, Secretary of Transportation Pete Buttigieg, Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Marcia Fudge, Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona, and Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Michael Regan.

Demonstrators weathered an unseasonably hot March day with temperatures climbing into the mid-80s. Many of the people in attendance waited more than four hours in the weather to finally make their way across the bridge.

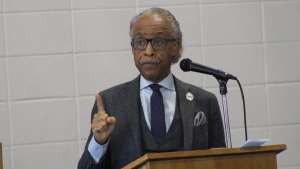

Other key figures in the Civil Rights Movement joined Harris for the march Sunday including Rev. Al Sharpton and Rev. Jessie Jackson.

Rev. Al Sharpton delivers the keynote sermon at the 57th annual Bloody Sunday commemoration in Selma, Ala. on March 6, 2022. (Jacob Holmes / APR)

Sharpton delivered the keynote sermon to Brown AME church earlier Sunday morning. Brown AME is the church where the original march began, and where bloodied protestors returned after being beaten by lawmen.

Sharpton compared the bridge to monument stones erected by the Hebrew people after their exodus from Egypt.

“What do these stones mean?” Sharpton asked. “Some of us take this as a commemoration weekend rather than a continuation of struggle … This is about connecting what the bridge symbolizes that is being disaffected in these times.”

He continued, telling the congregation that the Hebrews lost sight “moments after they were liberated,” leading to their time of loss in the wilderness.

“”We’re just like the children of Israel,” Sharpton said. “As soon as we got to mainstream television, as soon as we got to mainstream culture, we start calling ourselves the N word, start calling our mommas ‘ho’s and ‘B’s— wilderness behavior.”

Sharpton called on the crowd to march across the bridge and reflect on those leaders— John Lewis, Martin Luther King Jr., Jessie Jackson— who led the way, and continuing to build on their legacies.

While trees are appreciated for their fruits, Sharpton said, it is also important to give attention to their roots, the foundation by which the tree continues to flourish.

Sherrilyn Ifill, president and director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, told attendees that the Black community has always “punched above our weight.”

“We changed the entire course of Democracy in the 20th century,” Ifill said. “So the question is, given the resources we currently have that they did not have, do we believe we are not equipped to be as consequential in the 21st century as we were int he 20th? I do not believe that.”

Ifill challenged the crowd to be active citizens and attend at least one public meeting quarterly, whether that be a city council, county commission or a local school board. She told attendees the proposed bans on Critical Race Theory across the country, including Alabama, are a response to limit the power of Black citizens.

“What are they trying to turn off now in their children? Empathy,” Ifill said. “They don’t want their children to learn about slavery, they don’t want their children to learn about the holocaust.”