A brief on COVID-19 and Alabama’s Black Belt published Tuesday by The University of Alabama’s Education Policy Center and in partnership with the Center for Business and Economic Research found that the disparities between urban and rural Alabama counties was amplified during the pandemic.

Alabama’s Black Belt saw a greater percentage of COVID deaths per population in the first year of the pandemic than the rest of the state, but after increasing vaccinations in the Black Belt, the rest of the state saw increases in COVID deaths while the Black Belt’s remained relatively stable, according to the report.

Emily Grace Corely, a student in the Masters of Public Administration program at the University of Alabama, said during a briefing on the report Monday that during 2020 the Black Belt’s average COVID death rate was 218 persons per 100,000 residents.

“In the rest of the state, which are the non-Black Belt counties, that was about 168 deaths per 1,000 population,” Corely said.

The center defines the Black Belt as consisting of 25 counties in the southern central and western areas, which includes all of Alabama’s majority minority counties.

Jessica McGraw, CEO and administrator of John Paul Jones Hospital in Wilcox County, told researchers for the report that hospitalized COVID patients in rural areas tend to have higher rates of chronic diseases or underlying conditions, such as diabetes, obesity, or heart disease.

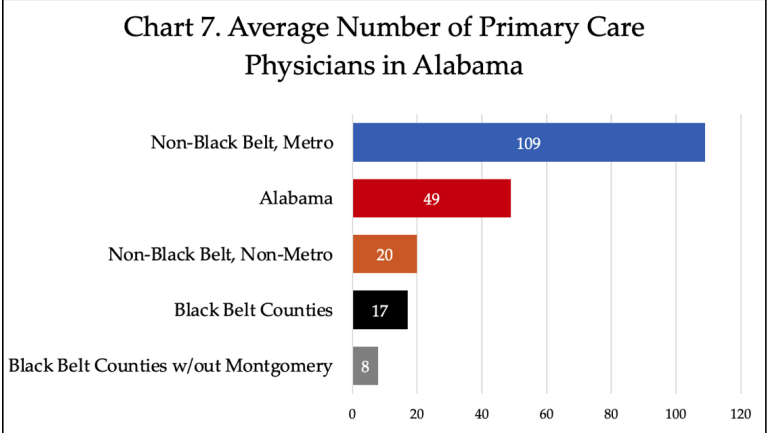

Graph from The University of Alabama’s Education Policy Center report.

The report notes that four of the top five Alabama counties with the highest death rates in 2020 were all in the Black Belt, which included Lowndes, Crenshaw, Greene, and Hale counties.

COVID deaths in the Black Belt fell from 218 deaths per 100,000 in 2020 down to 213 in 2021, while COVID deaths in the rest of the state increased by approximately 25 percent, from 168 per 100,000 to 211 per 100,000 in 2021, according to the report.

Researchers think higher vaccination rates in the Black Belt might have played a role in how those death rates changed between 2020 and 2021.

“Despite national trends showing that rural populations are less likely to be vaccinated than metro areas, as well as the historically-rooted vaccine hesitancy among African Americans, 7 of Alabama’s top 10 most vaccinated counties are in the Black Belt: Lowndes, Marengo, Bullock, Hale, Perry, Wilcox, and Clarke,” the report reads. “The other 3 counties in the top 10 are Madison, Shelby, and Jefferson—home to two of Alabama’s largest metropolitan areas.”

A lack of access to primary care physicians in the Black Belt is mirrored in all of rural Alabama, the report notes. The lack of access to the car those physicians provide likely resulted in the Black Belt’s larger numbers of COVID deaths, researchers found.

Black Belt counties, have on average 17 primary care physicians, compared to non-Black Belt metro areas with 109, and Alabama as a whole with 49. Non-Metro, non-Black Belt areas had 20 primary care physicians on average.

“While Black Belt counties face severe challenges to access primary care physicians—Lowndes County shares one physician for nearly 10,000 residents— access to primary care physicians is a general problem for all of rural Alabama,” the report reads.

Garrett Till, a student in the Masters of Public Administration program at the University of Alabama who helped research and write the report, said during the briefing that the Black Belt was just slightly behind other non-metro, non-Black Belt counties in terms of the number of primary care physicians, so they decided to remove the more metro Montgomery County from the equation.

“Which led us to an astounding eight primary care physicians on average per blackout County, not including Montgomery,” Till said.

Sean O’Brien, another student in the Masters of Public Administration program at the University of Alabama and an author of the report, said the Black Belt is not equipped to handle public health emergencies.

“They already have limited healthcare infrastructure, and that’s worsened by a lack of health care staff and professionals, which we’ve drawn that is the result of limited incentives and satisfaction amongst them,” O’Brien said.

“The Physician shortage one was very telling to us, and long term, If we want to move the healthcare outcomes in the right direction, and knowing how important access to health care is economic development, that’s something we ought to be thinking about,” Stephen Katsinas, director of the Education Policy Center told reporters during Monday’s briefing.

The report wraps with a set of policy recommendations. One such recommendation is to offer incentives for health care workers to increase access to care, including housing accommodations, student loan forgiveness for extended contracts in rural areas, and assistance with childcare.

The report also calls for significant investments in medical supplies and facilities to ensure the area is equipped to handle public health emergencies.

Tuesday’s report was the first in a series of studies on the Black Belt, slated to be released by the center in the coming weeks. Other studies will focus on access to STEM in K-12 schools, educational attainment and community college, poverty and housing market, mean worker commute time and infrastructure, goods versus services GDP and profiles of Black Belt community leaders.

The “Black Belt 2022” series is a follow up to the center’s “Black Belt 2020” series of reports, which looked at First Class Pre-K in the Black Belt, labor force participation, unemployment, internet access, access to healthcare and how to define the Black Belt.