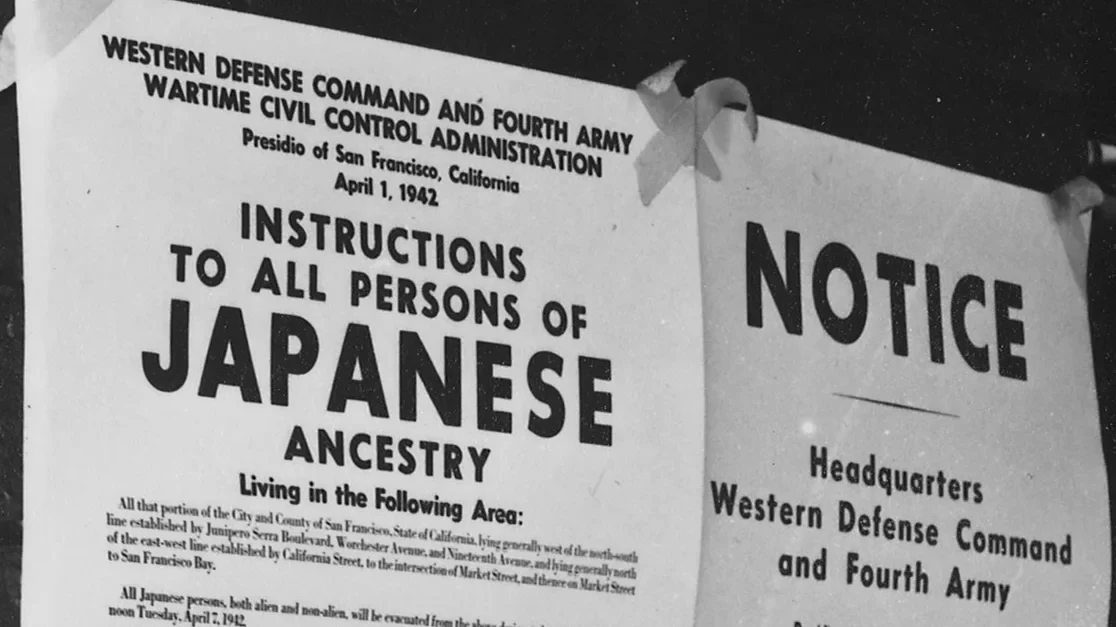

Eighty years ago this month, with the stroke of a pen, President Franklin Roosevelt in Executive Order 9066 effectively relegated 120,000 Japanese Americans to internment camps. Many of these American citizens were afforded no rights to object to their removal, and there was no procedure to prove loyalty to the United States. These citizens were interned solely because of their ancestry, nothing else.

In the aftermath of Pearl Harbor, there was widespread fear that the Empire of Japan might invade the West Coast. No doubt people were scared and on high alert, and, certainly, there was anxiety that turned rational people into frenzied xenophobes. But rather than deal with the reality of the situation, political leaders galvanized the country into transferring all these concerns into a government campaign to round up almost the entire population of Japanese Americans and relocate them.

Granted, they were not sent to concentration camps organized along the German or Soviet models. There was no plan to cleanse America of Japanese influence by premeditated death through forced labor. Nevertheless, these citizens were forced to leave their homes, abandon their businesses, and take their entire families to detention centers surrounded by barbed wire, guards and dogs.

And all of this was accomplished through legal and judicial means. Congress had passed an act giving the President broad and sweeping emergency powers to organize the country for total war. These wartime powers had precedent as Abraham Lincoln also used similar powers to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and incarcerate pro-secessionists. Ironically enough, Chief Justice Roger Taney, who authored the Dred Scott decision, warned Lincoln that such actions potentially violated his oath of office and could mean that citizens were no longer living under a government respecting the rule of law.

War, like other national emergencies, set in motion a series of restrictions subjugating the rights of individuals to the needs of the state. Fighting a war and making the decisions necessary to win cannot be done by consensus, but must be determined by leaders who have both national support and critical judgment to implement a plan for victory. Roosevelt’s almost dictatorial power was derived from legislative mandate, not usurpation. The hindsight of history clearly shows that he, like Churchill, was the man for the times.

But the internment of loyal American was perhaps an excessive use of presidential authority and a blot on American values. The need to systematically detain these citizens was no doubt a knee-jerk reaction to Pearl Harbor. But leadership is more than succumbing to situational whims and should be based on evidence or some proof that a threat existed. In fact, the exact opposite was true.

Military intelligence and the FBI found no disloyalty among the Japanese Americans. They uncovered no organized network of spies or saboteurs ready to support an invasion. The only reason for the detention was a suspicion based upon fear and a complete misunderstanding of Japanese American culture.

With no basis in fact, an assumption was made that anyone of Japanese ancestry would remain loyal to the Emperor. Like all foundations of racism, there is an assumption that people of similar backgrounds and appearance must share other, monolithic traits attributed to them by imaginary, irrational views. Political and military leaders simply agreed that these citizens would be disloyal, were probably spies, and posed a threat even though no evidence existed to support these assumptions. Thus, the President who told his country that “all we had to fear is fear itself” incorporated a racist fear into his policies that detained 120,000 Americans.

Despite the fact that this incident was humiliating and demeaning, almost 35,000 Japanese American men and women demonstrated their loyalty as United States citizens by serving in the military during World War II. In some cases, sons and daughters fighting for Roosevelt’s four freedoms had relatives detained by the same Uncle Sam. Units comprising these Japanese American troops were sent to the European Theater and distinguished themselves in battle. If there can be any humor to both the internment and the war, there was a story that Germans fighting in Italy were captured by one of these units and thought that the Japanese had changed sides and joined with the Americans to defeat the Third Reich.

Perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of deporting people based on race was the number of prominent liberals who blindly went along with the procedure. It is easy to see that military commanders on the West Coast truly believing that an invasion was imminent would want to evacuate civilians from a potential war zone. But it is difficult to understand how leaders normally inclined to support the rights of minorities, expand civil liberties and limit the powers of government would so easily embrace wholesale deportation without a hint of due process.

California Attorney General Earl Warren supported and encouraged this action. In the Korematsu case, Alabama’s own Justice Hugo Black wrote that “the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast.” Justice Felix Frankfurter provided cover to the administration by writing that the possibility of espionage and sabotage, not race, supported the government’s actions. Justice Robert Jackson disagreed, and in a vehement dissent argued that the government’s actions legalized racism in a manner no different than the “abhorrent and despicable treatment of minority groups by the dictatorial tyrannies which this nation is now pledged to destroy.”

Executive power is potent and requires conscientious leadership to assess and organize the needs of a nation to prepare a unified response to an existential threat. But even good leaders can succumb to fear and misunderstanding and attribute suspicions without substantial foundations.

In America, executive power is not absolute, and our rule of law requires that even emergency actions be reviewed and, if necessary, checked so that a looming or perceived threat is not used as a cover to suspend or deny rights based on political misperceptions.