The Alabama Department of Corrections suspended visitations at prisons statewide in March 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic, and 11 months later began issuing tablet computers to incarcerated people to help them connect to loved ones and access resources.

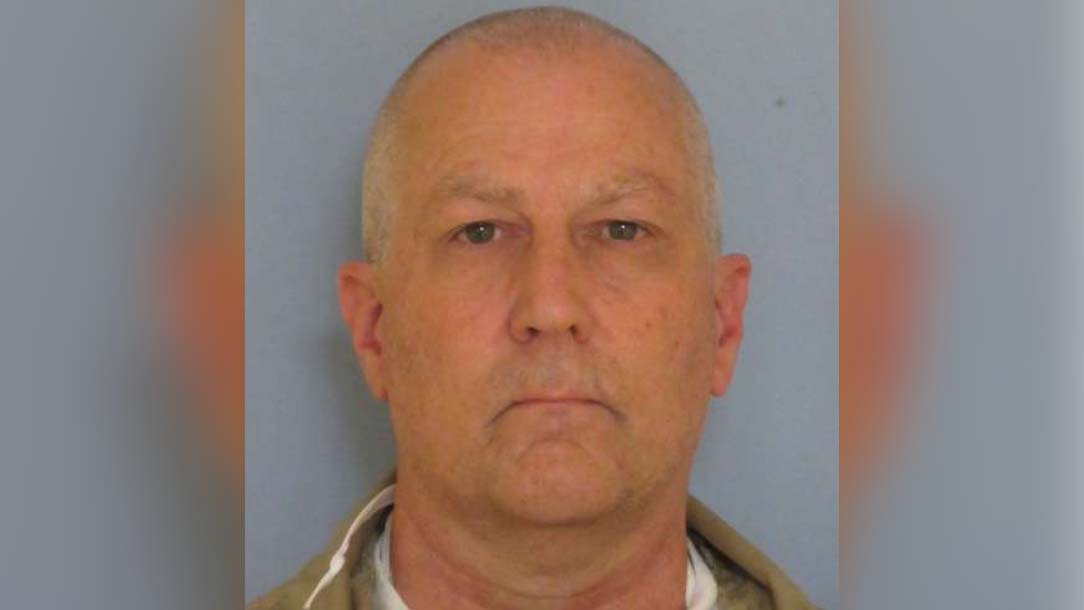

At least one prisoner used his tablet to try and cut his sentence short, however. Former Alabama House Speaker Mike Hubbard, convicted of numerous felonies related to ethics violations, used his device to try and get out of prison early by attempting to alter legislation that was in the works.

In 436 pages of electronic messages and 611 phone calls made through his monitored device, Hubbard used code words with friends and family in an attempt to insert language in a bill aimed at building new prisons that would have let him out earlier than his 28-month sentence. He found a willing accomplice in a state House representative, who state prosecutors didn’t name in court records, but the plan faltered in an unwilling Senate.

Hubbard also repeatedly denied in those calls and emails doing anything wrong.

“I haven’t figured out how I screwed the State yet,” Hubbard said in one recorded call.

Those electronic devices handed out in Alabama prisons are supplied and maintained by the Texas-based company Securus Technologies. The Alabama Department of Corrections in a late January press release said the department would begin issuing the Personal Education Devices (PEDs) in early February.

ADOC described the tablets as “corrections-grade device that offers digital educational and rehabilitative resources that otherwise would not be available in a prison setting” which would help supplement in-person classes which had been limited due to COVID-19.

“All ADOC inmates will be provided free and direct access to PEDs from which they can utilize available programming resources customized to their unique needs such as K-12 programs, GED preparation content, post-secondary and college courses, vocational training programs, job search programs, personal finance programs, spiritual/religious resources, self-help and re-entry resources, eBooks, and more,” ADOC said.

State prosecutors in a Nov. 15 court filing arguing against Hubbard’s request for an early release describe Hubbard’s electronic communication with those on the outside as “emails” but ADOC says the messages weren’t made through common email applications like Gmail.

“The secure communications applications include ‘e-messaging’ (which is being referenced in the litigation as ‘emails’ but are more accurately described as written digital communications between users registered in the system) and phone call services,” ADOC said in a message to APR on Wednesday. “These services enable inmates to send messages or place calls to their loved ones directly from the device. Our secure infrastructure allows for digital communications but does not allow incarcerated individuals to access the open internet or social media channels. Therefore, inmates cannot send ‘emails’ through traditional channels such as Gmail, etc.”

ADOC said those devices are loaded with “proprietary software that takes specific and significant measures to prevent misuse and detect any attempt at illicit behavior.” Before each phone call or message sent, Hubbard’s device would have let him know his communications were subject to being monitored and recorded.

“This excludes any communication subject to attorney/client privilege,” ADOC told APR.

While that may be true, a 2015 hack of Securus showed the company had illegally recorded more than 14,000 calls between prisoners and their attorneys. Securus in 2020 settled a lawsuit over those recordings, but denied any wrongdoing. Securus has also faced multiple lawsuits over allegations of unfair charges.