On June 9, 1964, Tuscaloosa Police Chief William Marable asked the Rev. T.Y. Rogers a simple question: “Do you intend to march anyway?”

Rogers, organizing over a period of two months, had gathered a group of nearly 600 protesters – mostly teens – in order to march against the Tuscaloosa County Courthouse’s segregated bathrooms and drinking fountains. Their march, however, had been declared unlawful.

But Rogers was not deterred.

Within seconds of responding “yes,” Marable arrested Rogers and other civil rights movement leaders. Minutes later, several hundred members of the United Klans of America — an organization headquartered in Tuscaloosa — and its sympathizers joined with two dozen local law enforcement officers. They attacked unarmed civil rights activists, mostly teens, with billy clubs, cattle prods, tear gas and water from a fire hose.

The little-known event, Bloody Tuesday, derived its name from the violence and extensive bloodshed visited upon the marchers.

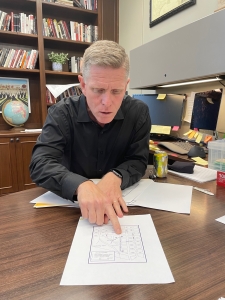

Dr. John Giggie, University of Alabama professor pointing to the site of Bloody Tuesday on June 9, 1964. (LIZ RYAN/SPECIAL TO APR)

“It carried a greater price in bloodshed than the march to Montgomery, than Selma, than Birmingham, than Anniston,” said Dr. John Giggie, director of the Summersell Center for the Study of the South and associate professor of history and African American studies at the University of Alabama. Interviewed in the fall of 2021 at his university office, Giggie plans to publish a book on Bloody Tuesday in 2022.

The local news and national wire services carried the story for a few days, grossly understating the violence and omitting mention of the UKA’s involvement. National news outlets moved on to cover Mississippi’s Freedom Summer and missing civil rights workers in late June 1964.

While the U.S. Senate was debating the Civil Rights Act of 1964 in Washington D.C., at the exact same time civil rights activists were on the front lines of the fight for civil rights on Bloody Tuesday, a moment which signaled the beginning of the end of the klan’s influence on segregation in Tuscaloosa.

From first-hand accounts of Tuscaloosa residents who marched on Bloody Tuesday, interviews with historians and other experts, a review of historical newspaper coverage and books written about Alabama’s civil rights movement, there is consensus that Bloody Tuesday was the seminal moment in the struggle with the klan to end segregation in Tuscaloosa.

“If the klan could be beaten in its own backyard, that’s a story, that’s a symbol of the movement’s strength and righteousness,” Giggie said.

United Klans of America and law enforcement attack civil rights marchers

That early June morning was a steaming hot and humid day. Despite the sweltering heat, Rogers wore a long-sleeved shirt, suit jacket, pants and a tie.

Rogers, the newly installed minister at First African Baptist Church, stood on one side of the sidewalk facing east on Stillman Boulevard, with 50 unarmed marchers behind him stretching around to the front entrance of the church. Only three months earlier, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King had recommended Rogers, one of his most trusted leaders in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference organization, to the church.

At 28 years old, Rogers was already a veteran of the civil rights movement. He had participated in the Montgomery Bus Boycott nearly a decade earlier while serving as King’s assistant pastor at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery.

Nearly 600 more people waited inside, mostly students from Druid High School and Stillman College. They’d planned to march to Tuscaloosa’s new county courthouse five blocks away to protest the “Colored” and “White” signs above the drinking fountains and the restrooms.

Marable, the police chief, faced west toward Rogers with several hundred people behind him.

“They were not all policemen because at that time Tuscaloosa only had 27 policemen,” said Danny Steele, who was 14 at the time, in an interview at the Van Hoose and Steele Funeral Home located next door to the church.

Danny Steele, co-owner of Van Hoose and Steele Funeral Home who participated in Bloody Tuesday as a teen, pointing to a photo of the SCLC, the organization his brother Charles Steeles runs now and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was head of at one time. (LIZ RYAN/SPECIAL TO APR)

“They were deputized on the spot, over 200 men that surrounded the church. And there was another group, if needed, that were two blocks away,” he said.

Civil rights activists believe most of the deputized men were klansmen belonging to the Tuscaloosa-based UKA, with offices on Greensboro Avenue, the dividing line between white and Black neighborhoods, right across the street from the new county courthouse. The largest klan organization in the U.S. by the mid-1960s, the UKA boasted thousands of members in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi and Louisiana, and fifteen other states, according to reports from the House Un-American Activities Committee.

“They were sitting in trucks and cars. They were making all kinds of noise,” said Willie Mae Ike Wells who was a college student at Stillman College in an interview at her home in Tuscaloosa in the fall of 2021.

“You could see the bats and the sticks and the instruments that they had in their hands, whatever they could find to use against us,” she said.

While many of UKA’s members directly participated in Bloody Tuesday, UKA Imperial Wizard Robert K. Shelton was not there. However, he likely ordered their participation as he had committed to his followers to fight the civil rights movement, according to Giggie.

“It would be hard to imagine Bloody Tuesday without the Klan,” he said.

The Tuscaloosa Fire Department also dotted the scene with a fire truck hooked up to a nearby fire hydrant so that they could turn on the water at a moment’s notice.

Marable and Rogers had kept an uneasy peace for the prior three months. Throughout the weekly marches that Rogers had begun in late April to protest the segregation signs at the county courthouse, Marable had provided some protection for the marchers, but not enough to stop the regular taunts and occasional use of mustard oil, which burns skin like pepper spray.

Unknown to Rogers at the time, Marable had been conducting surveillance of civil rights activists who attended the marches through photographs and tracking license plate numbers, according to documents obtained from the city.

That uneasy peace reached an end when Rogers refused to call off the march.

The chief directed one of his officers to escort Rogers over to a nearby police car where a rear passenger side door was open and awaiting the minister.

Marable also ordered the arrest of four other leaders of the movement, charging them with vagrancy, among other offenses. The charges were later dropped.

‘I thought I was going to die’

After the leaders’ arrests, Marable looked over at the marchers who had been standing behind Rogers. He’d likely expected that by arresting the movement leaders, the teens would not march that day.

“When the leaders are all arrested, you are to continue the fight, to struggle, to get to the Tuscaloosa County courthouse any way possible,” Wells said Rogers told her and other marchers the night before.

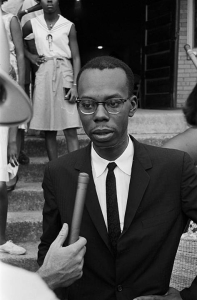

Rev. T. Y. Rogers speaking with a reporter after a civil rights meeting at Bailey’s Tabernacle CME Church in Tuscaloosa, Alabama on June 10, 1964.

(Courtesy of Alabama Dept. of Archives & History)

Seeing marchers continue to pour out of the church despite their leaders’ arrests, Marable instructed law enforcement to move them back into the church.

“All of a sudden, people were getting pushed back into the church. You could hear people screaming, hollering, crying because they were being cattle prodded. They were being beaten with billy clubs. They were being beaten back into the church. Bottles, cans, sticks and all were being used against us,” Wells said.

Irene Byrd, a 16-year-old junior from Druid High School at the time, in an interview at her home in Tuscaloosa in the fall of 2021, remembered walking from her home with a neighbor to the church to participate in the march.

“I don’t even think I got past the funeral home when I got hit on the side with a cattle prod,” Byrd said.

Byrd ran back into the sanctuary of the church with dozens of others who were seeking safety.

During the hour-long attack, police ordered the Tuscaloosa Fire Department to turn the fire hose on the church in an attempt to keep people from leaving the church.

When that failed, police officers sprayed tear gas on the marchers and threw canisters of the same into the church.

Harrison Taylor, who later became the city’s first Black postman and the first Black member of the city council, vividly recalled that morning.

“You had to come out of there because of the tear gas, you couldn’t stay in there,” said Taylor who was a 14-year-old freshman at Druid High School. “I was running so fast they couldn’t get me,” he said.

Steele and his older brother Charles, who lives in Atlanta and now leads the SCLC, were in the church when police and klansmen started attacking marchers.

“The tear gas disoriented you. You didn’t know where you were. Your eyes were burning. You couldn’t breathe. Your nose was running, and you were trying to escape any way you could,” Steele said.

Steele, his brother and another friend, Tick, who had a limp because of polio, walked to the back of the church with the intention of reaching the funeral home next-door that Steele’s father managed.

As soon as they stepped out of the church, they encountered a white policeman with a bat who yelled a racial slur at them and ordered them back into the church.

Steele and his brother turned to go back into the church. Tick remained at the door, yelling back at the white policeman.

“The last time we saw Tick that day, they had thrown him down, he was stretched out and the cop went and knocked all his teeth out,” Steele said.

Pallbearers, including Rev. T. Y. Rogers, around Martin Luther King, Jr.’s casket at the burial site on April 9, 1968.

(Courtesy of Alabama Dept. of Archives & History)

Wells and her brother Jimmy left the church through a side door. They intended to walk down 10th Street. Their goal was to reach the county courthouse as Rogers had instructed them.

They never made it.

“When we placed our steps onto the street, all of us were arrested and taken to the jail. We were fingerprinted and mugshots were taken,” Wells said.

Along with Wells and her brother, Marable and his officers arrested more than 90 other people that morning who stayed in the jail overnight.

Byrd remained in the sanctuary of the church where she was exposed to tear gas and found it difficult to breathe.

“I thought that I was going to die,” Byrd said.

By 11:15 a.m. — an hour after the attempted march and the violence it began — it was over.

Almost immediately after the confrontation, the marchers called it “Bloody Tuesday” because of the blood all over the sidewalk in front of the church. The church smelled of tear gas. Its stained-glass windows were smashed; the interior wrecked with broken chairs strewn across the sanctuary. Nearly three dozen people were taken to Druid City Hospital and hundreds more were injured; many had run to the Rev. Thomas Linton’s Barber Shop, a block from the church, to receive first aid.

Meanwhile, 800 miles away at the same time on the floor of the U.S. Senate in Washington, some Senators continued to filibuster civil rights legislation.

Reaction to Bloody Tuesday

Later that day and the next, local and national newspapers carried the story downplaying the violence and appearing to blame the unarmed teens for the violence against them that was initiated by police and klansmen.

On June 9, the Associated Press released a story that ran in dozens of newspapers across the country with the headline, “Police Rout Bottle-Throwing Negroes in Tuscaloosa Riot.”

The next morning’s Associated Press story gave the impression that it was the marchers — not law enforcement, klansmen and other white supremacists — who needed to be surveilled to stop any future violence.

“Watchful police kept a round-the-clock surveillance on the negro community in Tuscaloosa today alert for signs of new demonstrations in the wake of Tuesday’s bloody street battle,” reported the AP.

As Tuscaloosa residents were reading the headlines in The Tuscaloosa News — “Troublemakers Handed Warning” — in Washington, Sen. Robert C. Byrd, who had led the 60-day filibuster of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, finished his more than 14-hour speech at 9:51 a.m.

Byrd, a Democrat who would serve another 46 years in the Senate, was a former leader in the Ku Klux Klan in West Virginia.

Irene Byrd, former educator and civil rights activist who marched on Bloody Tuesday, as a student at Druid High School in the 1960’s. (Courtesy of Irene Byrd)

A little more than an hour later, the Senate roll call vote began, ending the filibuster of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

By noon, Marable released Rogers and the other civil rights leaders from jail.

The next day, June 11, Rogers’ lawyers filed a petition in U.S. District Court requesting that individuals arrested on Bloody Tuesday be handled in federal court, not state court, and that police stop interfering with peaceful demonstrations.

The news tapered off over the weekend, and Bloody Tuesday coverage largely ceased the following week. “The story was bigger than the attention it was accorded,” Giggie said.

By the time federal Judge Seaborn Lynne issued the order on June 24 to Tuscaloosa County to remove the “Colored” and “White” signs from the courthouse, all eyes were now fixed on neighboring Mississippi where three civil rights workers — James Chaney, Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman — had gone missing on June 21, 1964.

On July 2, when President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law, the courthouse staff had already removed the signs.

‘Our movement was nonviolent’

The city’s mayor and police chief blamed the violence on the marchers.

“Since they chose to ignore our advice and defy authority, we had no choice but to take the course of action that we did,” said Mayor George M. Van Tassel in his 1964 interview with The Tuscaloosa News.

In a few press reports, Marable implied that the marchers were the cause of the klan’s violence against them, and that if they hadn’t marched, there would have been no violence.

“I’m getting fed up with the whole bunch,” Marable told United Press International reporters. “If they keep messing with me, I’m going to clean out the church.”

Marchers, though, disagree that they were involved in the violence.

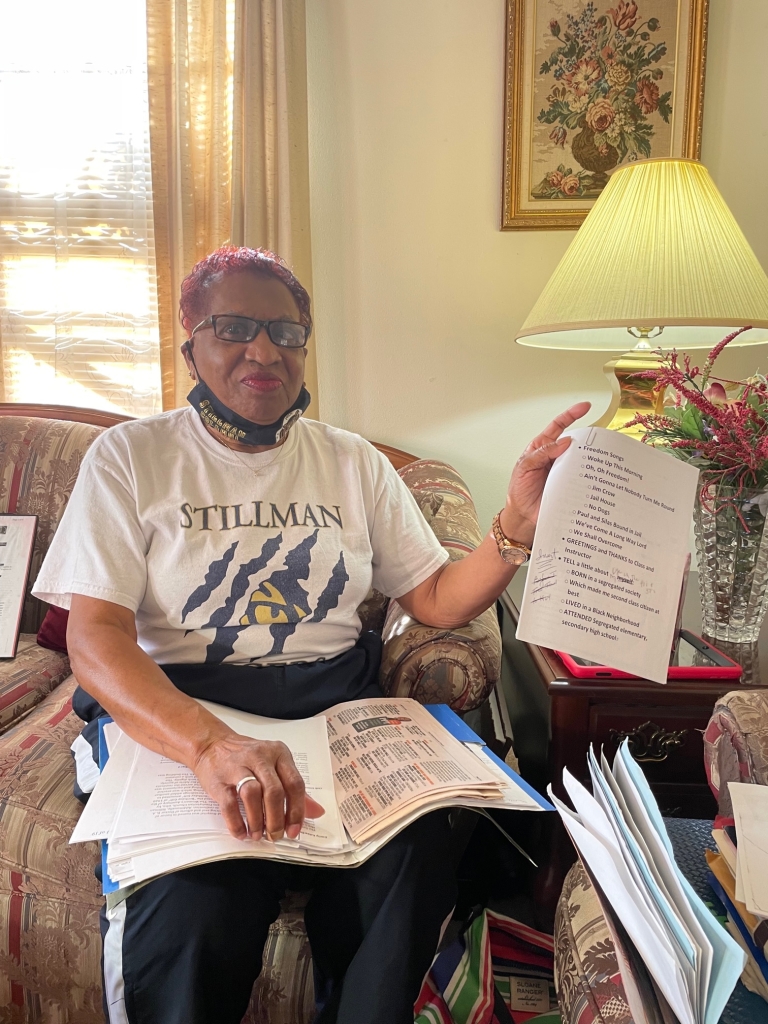

“Our movement was nonviolent so there was no need for us to destroy what we had,” said Wells, sharing a copy of the SCLC’s Handbook for Freedom Army Recruits, in an interview. Its code of discipline states: “We will refrain from violence.”

“We were not confrontational with anyone,” she said.

The UKA’s members’ involvement in enforcing the march ban likely had a different impact than Shelton intended. Rather than dissuade Rogers and the youth from taking action, the violence on Bloody Tuesday had the opposite effect.

“There was no turning back at that point,” Taylor said.

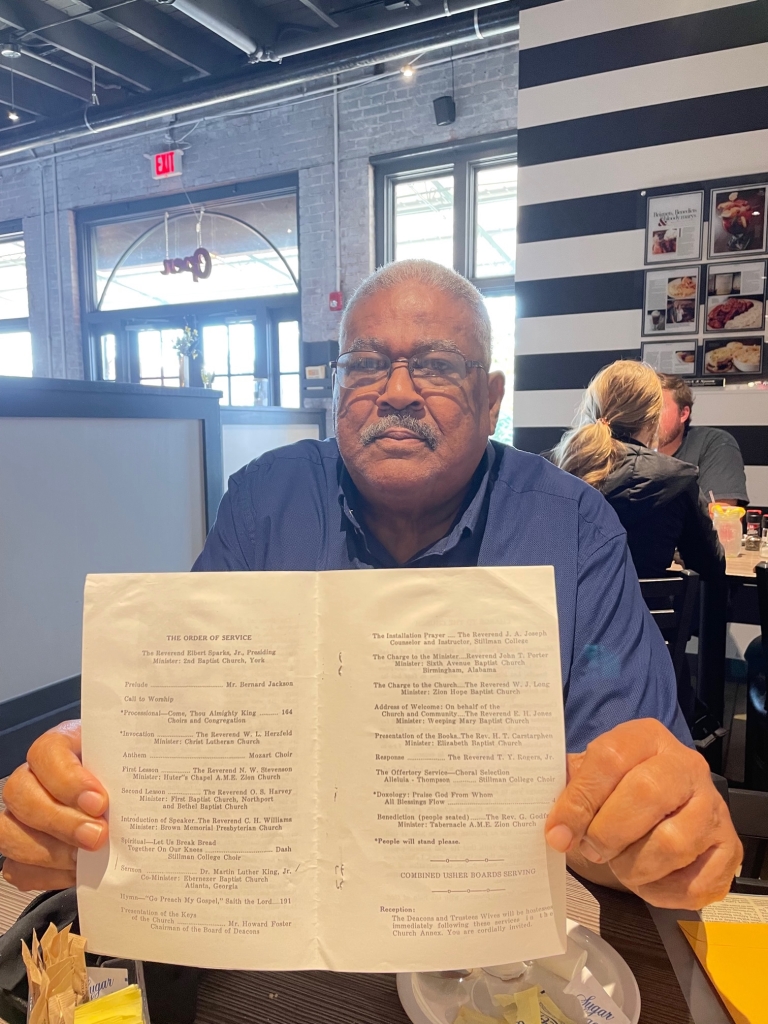

Harrison Taylor, former Tuscaloosa city council member and civil rights activist on Bloody Tuesday, holding a March, 1964 program where Rev. T.Y. Rogers was installed as minister at First African Baptist Church and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King spoke. (LIZ RYAN/SPECIAL TO APR)

The Tuscaloosa civil rights movement gained momentum, continuing to march and engage in direct actions, defying the klan and moving closer to ending segregation.

“We were relentless in our effort,” Wells said, “and we were not going to give up.”

Bloody Tuesday commemorated

Now, nearly 60 years later, even within Tuscaloosa itself, Bloody Tuesday is not well known or recognized.

Nor is it mentioned in the U.S. Civil Rights Trail sponsored by Alabama’s Tourism Department or in books such as Alabama’s Civil Rights Trail: An Illustrated Guide to the Cradle published by the University of Alabama Press, which is located in Tuscaloosa, or the popular Encyclopedia of Alabama.

The Tuscaloosa Civil Rights History and Reconciliation Foundation, a nonprofit 501(c)3 foundation, seeks to change that.

On the 200th anniversary of the city of Tuscaloosa in 2019, the foundation launched the Civil Rights History Trail in Tuscaloosa with 18 civil rights sites, including a large historical marker at the First African Baptist Church that tells the Bloody Tuesday story.

Starting in 2020, Tuscaloosa’s Central High School began teaching a course, History of Us Tuscaloosa, on the city’s history, including Bloody Tuesday, according to the foundation.

Scott Bridges, a retired University of Alabama music professor who helped to found and now co-directs the foundation, said that the foundation is working with the city of Tuscaloosa on plans to launch several museums on the site of the old city jail and at the site of Linton’s Barber Shop.

On Friday, the foundation will host a citywide Annual Reconciliation Dinner that is free and open to the public at a church on Greensboro Avenue to bring people together, according to the foundation’s Facebook page.

Taylor points to the devastating tornado in 2011 as evidence that Tuscaloosa can deal with its past and move forward.

“Black, white, brown, everybody was working together to recover from the tornado,” said Taylor.

“Young, old, everybody. We did a great job,” he said.

Change since Bloody Tuesday

Civil rights activists point to the integration of the schools, buses, lunch counters and restaurants, along with hiring Black people at local businesses, as signs of positive change.

And while the once bankrupted UKA re-emerged in 2012 under the leadership of Bradley Jenkins, it is a shell of its former self, according to Carla Hill, associate director of the Anti-Defamation League’s Center on Extremism. The UKA hosted an event in 2019 in Scottsboro with the United Federation of Klans, an umbrella group for the racist organization, but Hill said she hasn’t seen much activity from the UKA since then.

However, police brutality, ongoing discrimination and the lack of hiring Black people at the courthouse and other local area jobs continues to frustrate activists.

Willie Mae Ike Wells, civil rights activist who marched on Bloody Tuesday, holding the list of songs that youth sang in preparation for demonstrations. (LIZ RYAN/SPECIAL TO APR)

“It got better, but I think it’s reverting back to where we were,” Steele said.

Civil rights activists encourage vigilance to ensure that movement’s progress does not regress backward and that young people today participate in civic engagement activities such as voting rights.

“Don’t sit back,” Wells said, “and say that was then and this is now.”