Hours before the Alabama Legislature was to convene Thursday on the first day of a special session on redistricting, voting rights advocacy groups expressed concerns about the state’s redistricting process and the proposed new maps, which they say diminish the political power of minority voters.

“There’s still time for Alabama legislators to do the right thing here,” Jack Genberg, senior staff attorney for the Southern Poverty Law Center, said during an online briefing on redistricting efforts in Alabama and Georgia, hosted by the SPLC. “Alabama legislators should listen to communities of color and draw lines to give communities of color fair representation.”

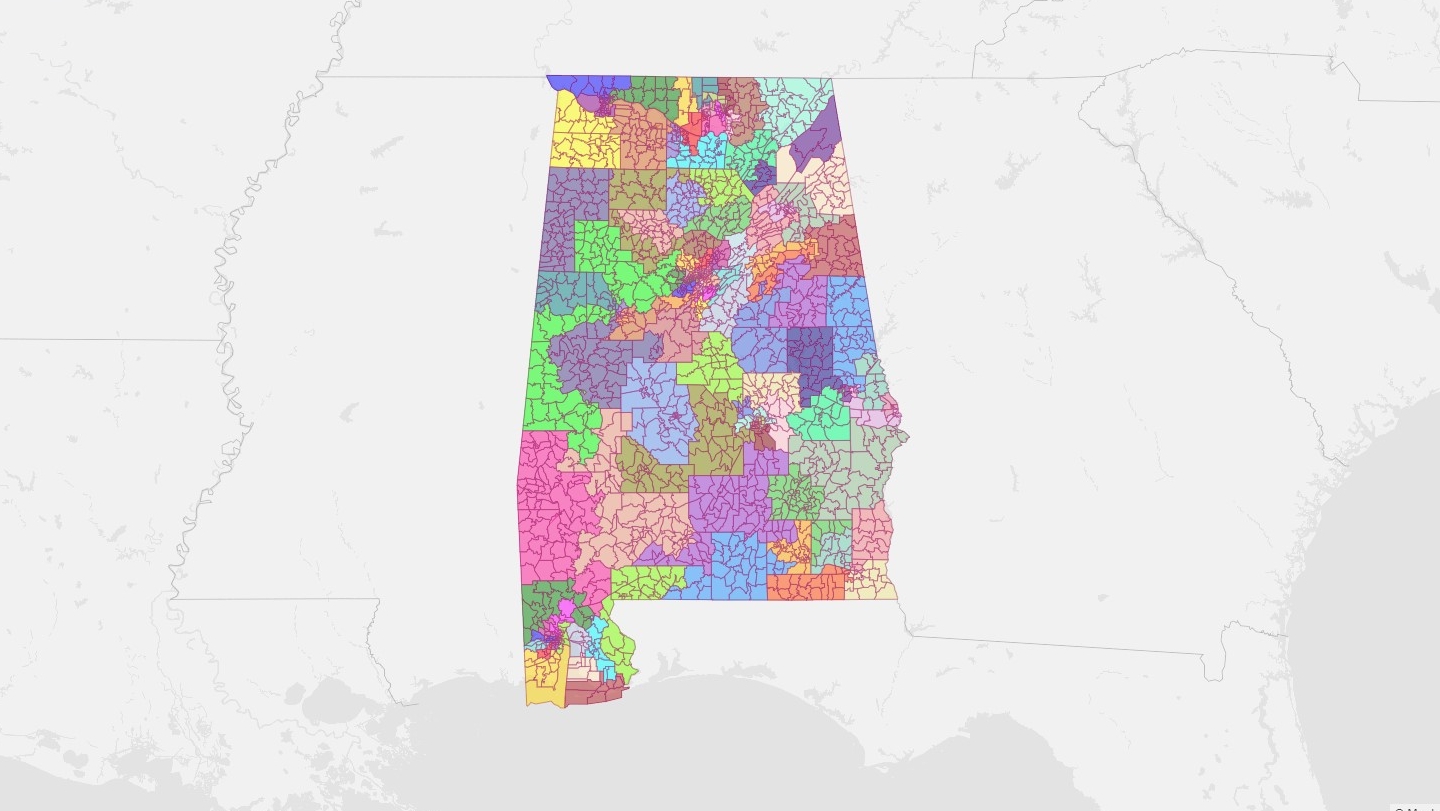

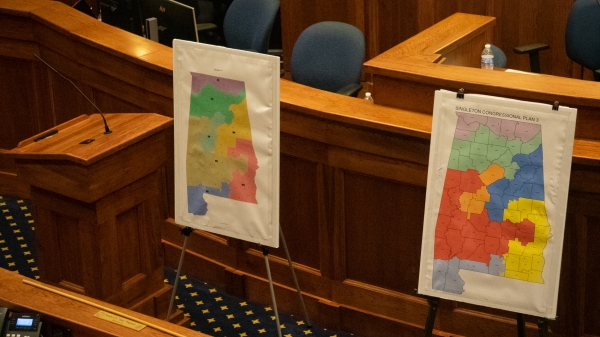

The Legislature’s Joint Reapportionment Committee in a Wednesday meeting approved along party lines new proposed districts for Congress, both chambers of the Legislature and the state school board.

Genberg expressed concern over what he described as “so called public input sessions” in Georgia and Alabama purportedly to solicit community input.

“But no data or maps were made available to the public at that time, so there was little opportunity for input,” Genberg said. The draft maps were published by Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, in a series of tweets Monday.

Felicia Scalzetti, a redistricting fellow with the Ordinary People’s Society and the Alabama Election Protection Network, said also troubling was the time of day Alabama’s public hearings were held.

“We had 28 public hearings, and 27 of them were between 9 a.m. and 4 p.m.,” Scalzetti said, noting that most people would have trouble attending a meeting in the middle of the day.

As for those drafts maps themselves, Scalzetti said she’s only had two days to study the maps, but what she sees troubles her.

“These new maps have minimal revisions to account for new population growth but the racist core and intention of these districts remain. The ratios are the same. We still have the same number of districts that are majority Black, that lean Democrat, that are again, fundamentally misrepresenting and cracking our communities,” Scalzetti said.

Alabama’s draft maps show districts that lean heavily Republican or heavily Democrat, Scalzetti said, which essentially makes a primary race the “real election.”

Alabama’s new draft Congressional map retains the state’s state one majority-minority congressional district, the 7th Congressional District, represented by U.S. Rep. Terri Swell, D-Alabama. Some Alabama Democrats are calling for two majority-minority congressional districts.

State Sen. Bobby Singleton during the state’s Joint Reapportionment Committee meeting Tuesday said he plans to introduce his own map that would create two majority-minority districts.

“We are 26 percent Black voting age population. We do not have 26 percent representatives,” Scalzetti said.

The draft House District map splits portions of Talladega County, Scalzetti said, against the wishes of residents there who spoke to the reapportionment committee.

“Talladega showed up to the public hearings. They did everything they were supposed to do. They followed the rules. They had one of the biggest showings,” Scalzetti said. “And they said unequivocally that they wanted Talladega kept whole in these maps, and that’s not what has happened.”

Scalzetti and others in the briefing discussed “packing” and cracking,” whereby those drafting new maps can pack like-minded voters into certain districts to limit their political power elsewhere, and break up, or “crack,” other like-minded voters into various districts to prevent them from reaching a majority in one. Such gerrymandering practices are often used to diminish the political power of minorities, which often leads to lengthy court battles.

Genberg discussed just such a lawsuit in Alabama in which a federal court in 2017 ruled that 12 of the state’s proposed districts in 2010 were racially gerrymandered, in violation of the Constitution and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, ordering them to be redrawn.

A 2019 article in The Intercept appears to show Sen. Jim McClendon, reapportionment committee co-chair who was in 2010 a state representative, worked with the late Republican gerrymandering expert, Thomas Hofeller, during Alabama’s 2010 redistricting cycle.

Hofeller’s files, included in that 2019 article, showed he was involved in the editing of a document called “Reapportionment Committee Guidelines for Legislative, State Board of Education, and Congressional Redistricting State of Alabama” and worked on those edits with McClendon.

Some of Hofeller’s documents indicate he was dividing Alabama’s district lines based on race to benefit Republicans and dilute minority votes. Asked about that by APR in 2019, McClendon declined to comment.

A federal court ruled that congressional lines Hofeller helped draw in North Carolina in 2016, were unconstitutional racial gerrymandering.

“Unfortunately, partisan gerrymandering is legal,” Scalzetti said. “You can say that I drew this map to disenfranchise Democrats, and that is legal. You can’t say I did it to disenfranchise black voters, but you can hide it.”

The redistricting cycle is Alabama’s first since the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 ruling in the Shelby V. Holder case that invalidated a critical section of the Voting Rights Act, Section 5, which held that nine states including Alabama, had to get voting rules approved by the federal government to ensure the changes didn’t negatively impact minority voters.

Caren Short, senior supervising attorney with the Southern Poverty Law Center, during Thursday’s briefing discussed two pieces of federal legislation she said could strengthen protections during redistricting.

The Freedom to Vote Act would ban partisan gerrymandering and strengthened protections for communities of color, Short explained, and the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act would restore the protections of the Voting Rights Act dismantled in the 2013 Supreme Court ruling.

“The freedom to vote act is like the cure against many of the partisan, opaque racially-discriminatory ills with the current district drawing process occurring in the special legislative sessions,” Short said. “The Voting Rights Advancement Act is like the vaccine against future election changes made by states like Alabama and Georgia, with long histories of racial discrimination in voting.”

Genberg said the SPLC is very concerned that the political maps that emerge from the current processes “break up and dilute the voting strength of communities of color.”

“We hope the legislators will do the right thing,” Genberg said. “But if they don’t, they’re going to invite costly years-long litigation.”