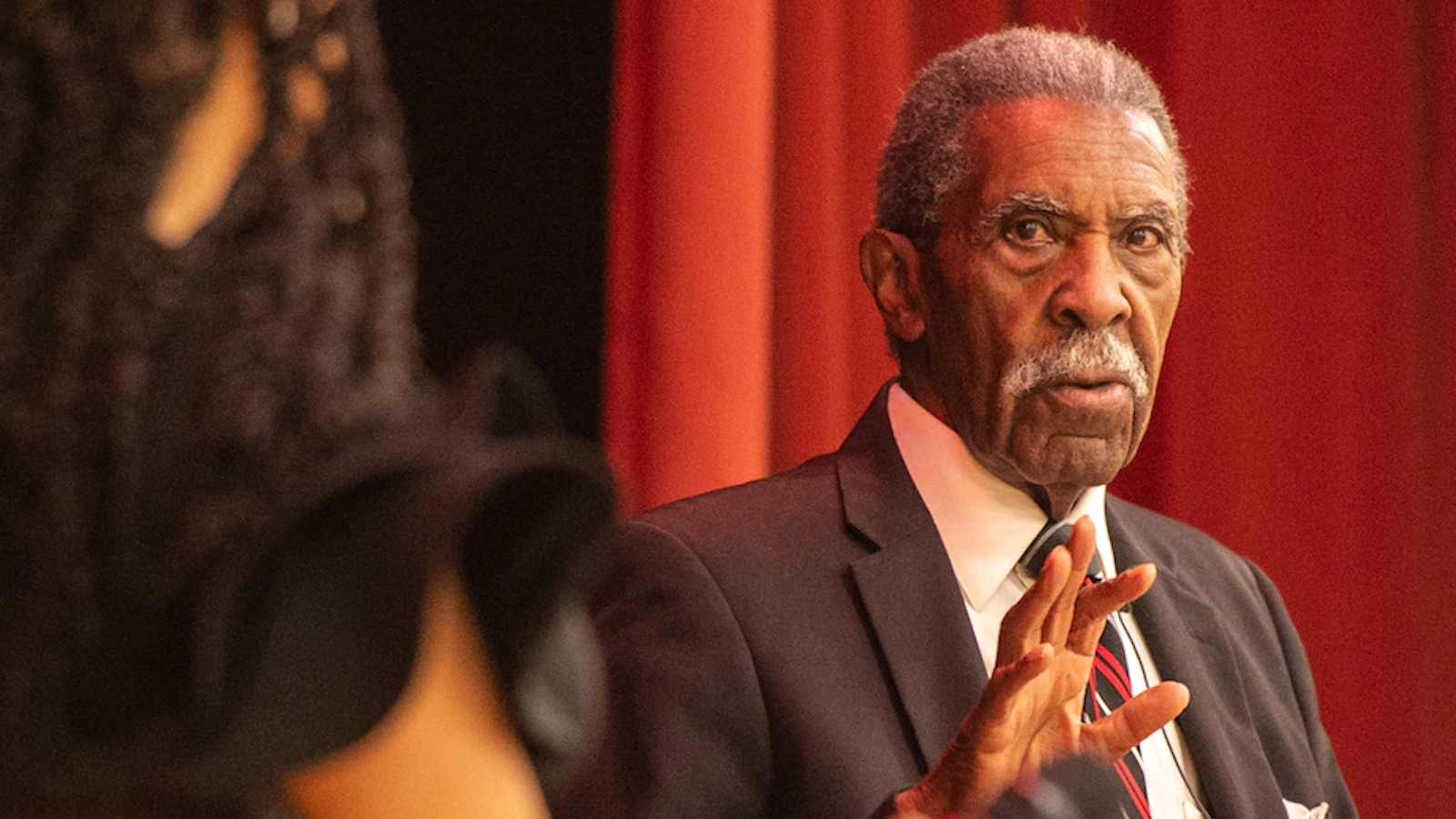

Harold Alonzo Franklin died last week at the age of 88. He may have been one of the most important Alabamians unknown to people in and out of the state.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Jim Crow became a Call to Arms in Alabama for many white politicians. Gubernatorial, mayoral, and even candidates for the State Superintendent of Education affirmed their allegiance to segregation in political advertisements. It only followed that the desegregation of the University of Alabama, the all-white public flagship, by its first Black students, namely, Autherine Lucy, Pollie Anne Myers, Vivian Malone, and James Hood, resulted in protracted legal finagling, riots, and an infamous stand in the schoolhouse door by Governor George C. Wallace.

The U. S. Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision portended the end of separate but equal public education in the United States compelling the State of Alabama to drop “Negro” from the Alabama State College for Negroes in June 1954. It is this context that Harold Franklin’s admission to Auburn University in January 1964 as its first Black student, should be understood.

Harold A. Franklin graduated from Alabama State College, now University, in May 1962, the first class to receive unaccredited degrees. The circumstances of the college’s loss of accreditation became a focal point in Franklin’s battle with Auburn University and the State of Alabama.

In February 1960, Alabama State College students staged the state’s first “sit-down” demonstration at the Montgomery County Courthouse Cafeteria. They chose the courthouse because it was publicly owned even though the courthouse cafeteria was not. The racially segregated cafeteria lunch counter represented an affront to these Black students as United States citizens protected by the United States Constitution. They boldly and correctly proclaimed, “If we are punished because of these beliefs, then we are guilty … Our textbooks have taught us this. Our education has prepared us for citizenship.”

Alabama Governor John Patterson took umbrage at such insubordination of state laws. He ordered Alabama State College and the Alabama State Board of Education to punish the sit-in ringleaders. The expulsion of nine students followed without warning or a hearing. Twenty other sit-in students received probation. The removal of ASC President Harper Councill Trenholm by the State Board of Education and the denial of accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools in the fall of 1961 capped off the calamity. Local papers speculated that the 1960 spring student uprisings precipitated the College’s dénouement. Denied due process, outraged ASC students protested on campus and at the State Capitol warning, “Can’t Go to Alabama. . . We’ll Go to Auburn.”

Attorney Fred Gray filed a complaint on behalf of Harold Franklin against Auburn University Graduate School Dean William V. Parker in federal court in August 1963. NAACP Legal Defense Fund Attorneys Jack Greenberg, Constance Baker Motley, and Leroy Clark assisted Gray. The Graduate School argued that it denied Franklin’s admission because he graduated from an unaccredited college. Gray et al asserted that Auburn turned down Franklin because of his race and color of skin.

The U.S. Justice Department under Attorney General Robert Kennedy supported the Franklin complaint as an amicus curiae.

Middle District Court of Alabama Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr. heard the complaint and handed down his opinion on November 5, 1963, three days after Harold Franklin’s thirtieth birthday. Judge Johnson wrote, “. . . the State of Alabama is as much to blame for the plaintiff’s inability to satisfy Auburn’s requirement for admission to its Graduate School as if it had deliberately set out to bar the plaintiff from Auburn because he is a Negro.”

On November 6, 1963, a headline in The Burlington Free Press read, “Wallace Calls Admitting Negro to Auburn ‘A Tragic Decision.’” Governor George Wallace made those remarks at Dartmouth College arguing that Franklin’s admission lowered the standards of the University. A day later, State Superintendent of Education Austin R. Meadows reported in the Birmingham News that the state provided funding for qualified Black residents interested in attending graduate school not available at one of the Alabama’s Black colleges but offered at white state colleges. The state paid a portion of a Black student’s room, board, tuition, and even paid for a roundtrip railroad fare. This funding covered law, medical, and dental schools. In existence since 1948, the program specified, “If a sufficient number of Negro students sought graduate work in areas not included under the state’s contract with Tuskegee Institute, such courses would be added to Alabama State College and Alabama A & M College.” Tuskegee’ s School of Veterinary Science became the segregated training facility for would-be Black veterinarians.

Franklin’s rebuff of the out of state graduate school program conceivably explains the subsequent approval of a graduate history program at Alabama State University.

On November 26, 1963, the Auburn Board of Trustees passed a resolution “to preserve the peace when Harold Franklin, a Negro, is admitted on January 2, 1964.” The Board also opposed the “unwarranted action of the Federal District Court affecting accreditation standards of the Graduate School of Auburn University” instructing Auburn President Ralph B. Draughon to appeal Judge Johnson’s order. The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit affirmed Judge Johnson’s injunction.

President Draughon thanked students, faculty, and staff for “the quiet integration of Auburn University.” One can only imagine the disquiet Franklin felt as the token Black student on campus. Rumors and innuendo abound over his alleged unfitness. Few knew or maybe cared that he graduated from Alabama State College with honors as a history and social science major, or that he wrote poetry, spent seven years in the U. S. Air Force where he served in Korea, or that he aspired to enter the foreign service.

Fred Gray and the NAACP did not seek Harold Franklin’s admission to Auburn University because they believed HBCUs were inferior; Fred Gray and the NAACP sought Harold Franklin’s admission to Auburn University because they believed so long as white schools remained “white” the notion of white superiority would remain a fiction in Alabama and in America.