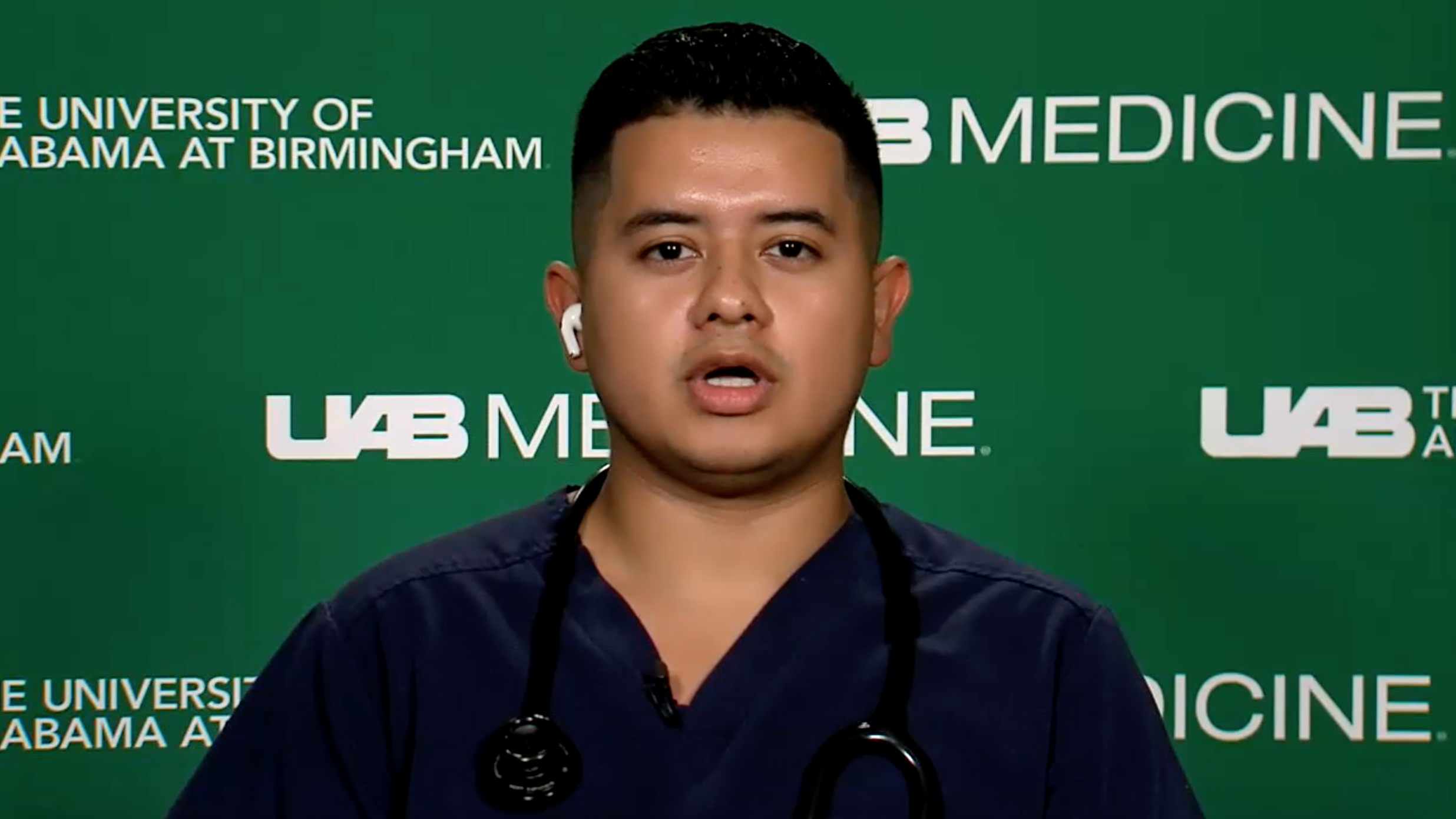

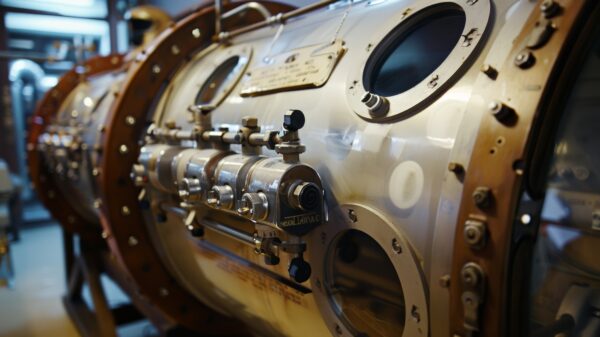

Anderson Lopez Castillo has worked in an intensive care unit at the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital for the last 11 months of the pandemic. Many aspects of the job wear him down, he said, but particularly heartbreaking is seeing patients who can’t talk about what’s happening to them or say any last words to their families.

“Most of the time, patients will voice concerns and, you know, regrets, early on in their stay and then by the time I’m seeing them, they’re no longer able to voice really anything because now they have a tube down their throat or they have a tracheostomy now, or they’re sedated, they’re paralyzed, because if they’re even awake for more than a few minutes, they’re coughing so much that they’re unable to breathe,” said Castillo.

The 24-year-old joined the ICU staff straight out of nursing school. The experience has been taxing enough that he has doubted his career choice. With less than a year in, it feels like he’s been at it for three or four years already, he said.

“We definitely didn’t expect to be this tired 11 months out of orientation,” he said.

There have been 676,795 cases of COVID-19 documented so far in Alabama as of Friday, with 12,103 total deaths. There were 18,237 new cases reported last week as of Friday and 2,845 hospitalizations statewide. Of those, 84 percent were unvaccinated, according to the Alabama Hospital Association.

As of Wednesday, UAB was caring for 166 people with active COVID infections and another 39 who are deemed no longer contagious but still need hospitalized care.

Castillo said he and other staff struggle to maintain their best bedside manner as they move from one patient to another, sometimes dealing with the emotions that come with losing a patient who they’d come to know very well over a long hospital stay. COVID patients can be hospitalized anywhere from 14 days to 250 days, with stays averaging about 100 days.

He’s present as people he’s been fighting to keep alive die, and he’s there when their loved ones cry over their body.

Then he has to walk into another patient’s room and pretend that none of that happened, and that the person in front of him has a shot at making it out alive.

“You’re almost not even sure of what emotions you’re feeling at this point,” Castillo said. “You’re frustrated, you’re angry, you’re happy for a second when something goes well but you can’t get too happy because you have to be defensive of your own emotions, and even your family member of the patient’s emotions because you’re also trying to protect them.”

Terri Poe, chief nursing officer at UAB, said she has been a nurse since 1986 and has never seen this level of stress among her colleagues. They don’t have enough to time to emotionally and physically regroup and fortify themselves before they’re dealing with another wave that plunges their units into crisis mode, bringing a shortage of beds, ventilators and other staff.

“Three surges in an 18-month period is the highest stress load I’ve ever seen in nursing,” Poe said.

There has been some relief from the Helping Hands program, which brings in non-staff medical personnel who can help with tasks to reduce the workload of bedside nurses.

Emotional support from the community has been critical to the mental and emotional resilience of frontline medical workers, she said.

“I can’t say enough about what it means to the team to get cards and letters and messages from our local community,” she said, saying that notes from children have been particularly helpful. Every team member received a Valentine’s Day card from a local child in February.

For Castillo, the camaraderie of his colleagues has been a primary inspiration. They plan trips to the beach or go out to dinner on their days off. Sometimes they just vent.

He also finds motivation in seeing patients return to their families, he said. He hasn’t had one patient who has survived the ICU who didn’t express that they wished they’d taken some better level of precaution before they contracted the virus, be it getting vaccinated, wearing a mask or social distancing. Their recoveries help him find the strength to stay fully committed to the patients whose lives still hang in the balance.