In Hoover City Schools, the superintendent informed parents last week that schools would no longer be notifying them if their children were potentially exposed to a COVID-positive student or teacher.

In Madison County schools, school nurses were told they didn’t have the authority to quarantine students, and, according to three parents of students in that district, parents were told that it was up to them if they wanted to quarantine their kids after exposure.

In Limestone County schools, the superintendent said its schools were notifying parents of exposure, offering Alabama Department of Public Health guidance to parents and recommending that they stay home — but, he believes, the system lacks authority to prevent the students from returning to campus.

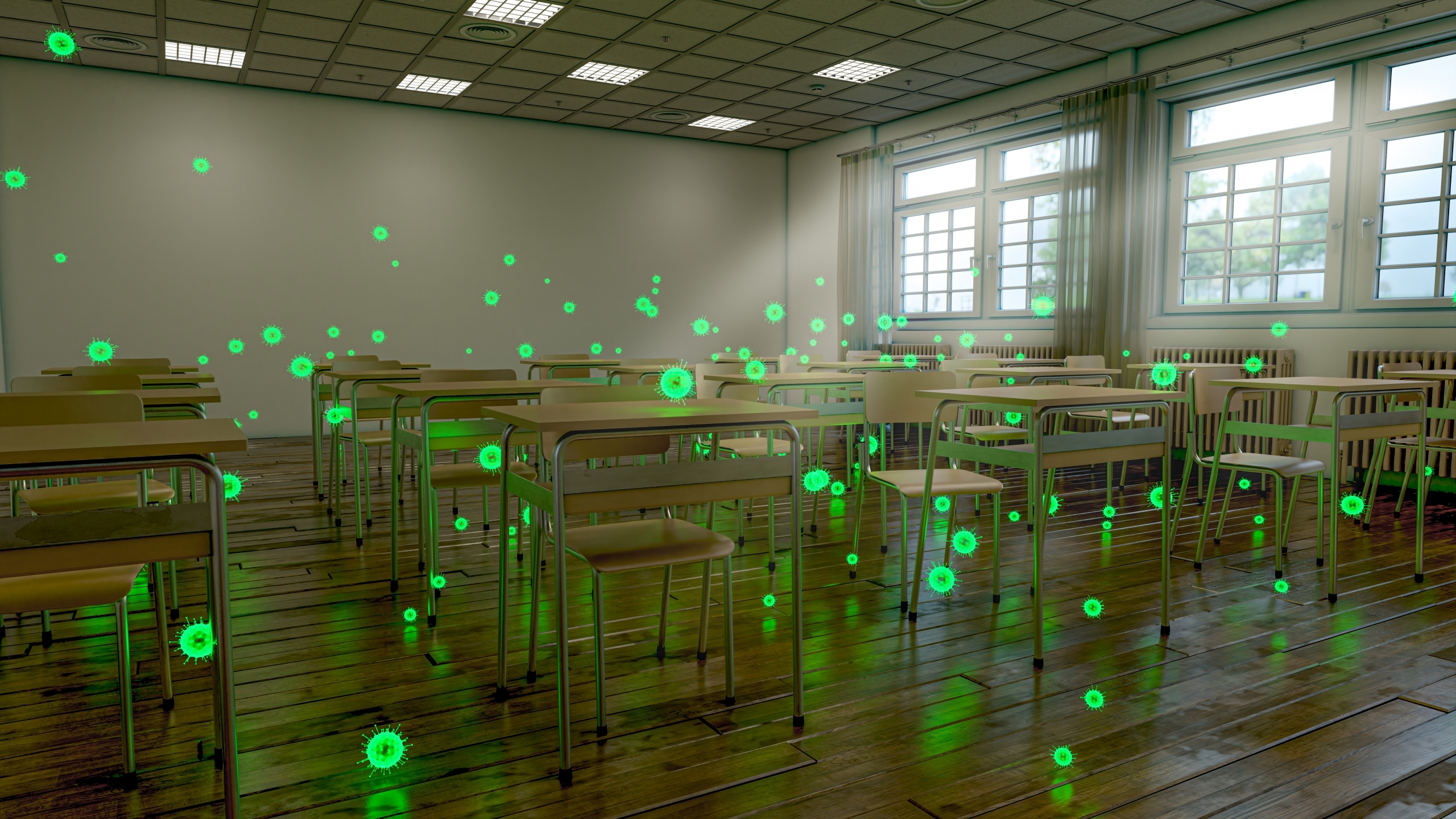

This is a small sampling of the chaotic, confusing life that Alabama’s public school students, parents, teachers and administrators have been living through for the first few weeks of the school year. With COVID-19 cases sweeping through the state — and with school children more susceptible than ever to the virus — state leaders, either by choice or because they lack the authority to do more, have taken a mostly hands-off approach to governance on the issue, allowing the various districts to set their own rules about masks and create their own plans for dealing with contact tracing and quarantining.

That hands-off approach has created a mishmash of rules and procedures that vary from district to district, often leaving parents confused and angry — and teachers and administrators in the middle.

“They told us, on one hand, to keep the students at home who come in close contact with those who test positive (for COVID), but then they also told us that we don’t have the authority to demand that, so we were just supposed to ‘recommend it,’” said one county superintendent who spoke to APR on condition of anonymity. “Now they’ve come back and tried to clear some of that up, but it has been rough for us. We’re trying to do the right things and keep everyone safe, and everybody’s mad and confused and the phone is ringing off the hook. It’s exhausting.”

Unless Gov. Kay Ivey declares a state of emergency and orders another statewide mask mandate — something she has promised she won’t do — there is little that can be done by anyone to rectify the situation. At a recent AARP Q&A session, state Superintendent Eric Mackey attempted to explain the many issues at play, from his lack of authority to issue a mask mandate to a breakdown in communication between state departments.

“I agree that all of this can be very confusing,” Mackey said. “Schools cannot order people into quarantine and that’s one of the confusing points out there. You know one of the issues is we don’t necessarily know that public health is quarantining somebody. We don’t always know that. There are many factors at play in that.”

The confusion became so common throughout the state, Michael Sibley, the director of communications for the Alabama State Department of Education, told APR that last week state health officer Dr. Scott Harris sent a new letter to county superintendents to reiterate the state’s policy on contact tracing and quarantining students. That letter, Sibley said, was sent because “some school systems are identifying and then notifying ‘close contacts’ but not excluding those persons from campus.”

“The letter from Dr. Harris was partially to make it clear that if you identify close contacts, you have to exclude them from campus (emphasis his) unless they meet one of the exclusions outlined in the Toolkit,” Sibley said.

The Toolkit was included in a packet of information sent by ADPH to school systems across the state in late-July, just before many of them were getting set to welcome students back. Reading through the information, it’s easy to understand how superintendents and principals might be confused by the instructions, particularly the portion that reminds superintendents that they have no legal authority to quarantine students.

ADPH has also informed districts that they can partner with ADPH to conduct contact tracing in their schools. If the schools opt to participate in the tracing, they must prevent any “close contact” students from returning to campus until the quarantine period has passed. However, if schools opt not to participate there is no requirement to identify “close contacts” or to bar them from campus, or to even notify parents that their child was in close contact with a COVID-positive student or teacher.

In response, some schools have chosen to do the bare minimum, opening without mask mandates, without tracing and with minimum effort expended to identify potential cases. Some districts have participated in the ADPH contact tracing and are actively working daily to identify potential cases and sequester close contact students. And still, others have decided to split the difference and notify parents of the contact and let them make the decision on whether to send their child to school.

It has created a never-ending cycle of anger, with principals, teachers and superintendents caught in the middle between anti-mask parents who are screaming about freedoms and tyranny and pro-contact tracing parents who are outraged that the systems aren’t following CDC guidelines. Lawsuits have been threatened — there have been at least a dozen letters written by attorneys and doctors to various school boards around the state — and protests are common at every school board function.

In the meantime, there seems to be no movement from the governor’s office or the State School Board to implement an overriding state policy that might settle any of the more prominent issues and give superintendents cover. (At the most recent state school board meeting, the members spent the majority of their time on a resolution that essentially bans the teaching of what they seem to believe Critical Race Theory is.)

And as they fiddled, the schools were on fire:

- Cullman County Schools saw more than 400 students and teachers quarantining last week because of either positive tests or being exposed.

- Green County Schools last week switched to virtual learning after eight days of school, with two students having tested positive and two teachers quarantining.

- Colbert County elementary school on Aug. 13 sent all students home for 10 days, noting in a statement that the district’s policy requires a shutdown when “one school’s population reaches over 18% of isolated or positive COVID cases….”

- Lee County Schools saw 193 confirmed cases among students and staff within the first two weeks of school, prompting it last week to announce it would be sending all close contact students and staff home, after beginning the school year without requiring close contacts to quarantine, according to WTVM 9.

- At Madison City Schools more than 100 students tested positive less than two weeks after start of school, prompting administrators to reevaluate social distancing in classes, bring back contact tracing and requiring close contacts to quarantine.

- Pike County Schools closed on Aug. 20 to undergo a deep cleaning because of rising cases there, the system announced.

- Elmore County schools were forced to reverse course and mandate masks after more than 100 students and 16 staff tested positive for COVID in less than a week.

- Blount County schools implemented a mask mandate on Monday after seeing six of its county schools transition to virtual classes because of rising COVID cases.

- Hatton Elementary school transitioned to virtual classes less than a week into the school year after nearly 20 percent of the students and staff tested positive for COVID.

- Three schools in the Lawrence County system moved to virtual learning last week due to rising COVID cases.

This is just a sampling of the issues, and most superintendents who spoke with APR said they expect the situations to get worse before they get better. They expect that because that’s what doctors across the state are telling anyone who will listen that the delta variant of COVID will peak sometime around Labor Day in this latest wave. The fallout from the massive number of hospitalizations and cases could last months.

Alabama’s public schools will not be spared. But hopefully, the early issues will lead to a clearer understanding and better results.

“In the end, all we want to do is keep the kids safe and go back to normal — someday,” said the superintendent.