Under normal circumstances, an intensive care unit at University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital may have two pregnant women in its care. It currently has five times that.

“It’s cliché to call this unprecedented because that’s what we’ve said at every turn, but truly, we’ve never had this number of pregnant women in my ICU,” said Steve Stigler, medical director of the UAB Medical Intensive Care Unit.

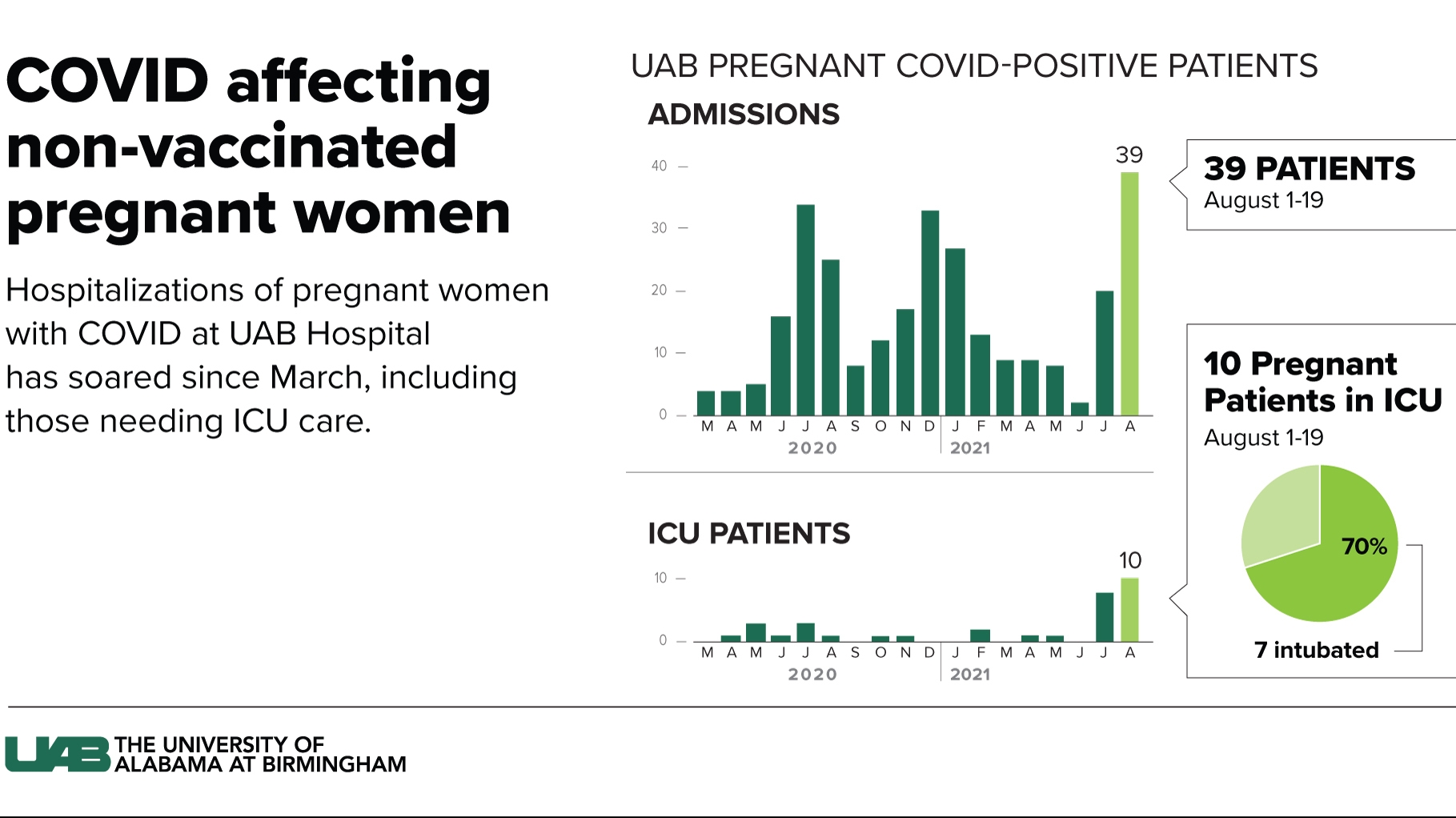

Thirty-nine COVID-positive pregnant women have required hospitalization at UAB Hospital this month. Two months ago, pregnant patients visiting the hospital for routine obstetric care were showing low positivity rates when they were tested. Now, as the delta variant drives infection rates higher than all previous records in the state, half of women arriving for any pregnancy-related issue are testing positive.

Ten women were in the ICU as of yesterday, with seven on ventilators.

“And that is really a significant increase from what we see in intensive care in pregnancy, which is usually considered — 99 percent of the time — to be a low-risk, happy time of life,” said Akila Subrananiam, associate professor in the UAB Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine. “And now we’re seeing patients with an incredible number of complications and all of the downstream effects of that.”

Back in January, before the delta variant superseded the original COVID-19 virus as the primary cause of new infections, there was a general consensus that pregnant women were better off getting vaccinated and risking unknown potential side effects than risking increased likelihood of complications or death from the coronavirus.

This week, new data caused the CDC and all major reproductive health organizations to adjust their guidance to strongly recommend vaccination for pregnant women universally — any trimester, as well as postpartum and mothers who are breastfeeding. UAB Hospital is offering the vaccine to unvaccinated women who are receiving care for high-risk pregnancies as well.

Some of the women’s conditions have required preterm births to ensure the health of the mother and baby, said Audra Williams, an assistant professor in UAB’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

With the delta variant being two to three times more contagious than the previous virus, it is finding many more people and making them sicker, possibly due to the larger viral load in the body of an infected person. That adaptation is how the variant increases its chances at survival — the more of it a person sheds as they breathe, the higher the chance it will find new hosts.

It poses a litany of threats to pregnant women and their fetuses. Their lungs are especially vulnerable to respiratory infections like COVID because they are already compressed by the fetus, which is also drawing on the oxygen they inhale. Before taking the serious step of intubation, medical staff can ease a COVID patient’s difficulty breathing by laying them face down in the prone position, usually for 16-18 hours. That can become less of an option the later a woman is in her pregnancy because her belly is usually bigger.

If the virus prevents oxygen from being absorbed by the mother’s lungs, the fetus loses that oxygen, too. That’s what necessitates a preterm delivery, in these cases more often done by caesarean section or induced in the ICU, which is not the ideal setting for doctors to perform a delivery. Infants are then at higher risk for severe complications like brain bleeding, Subrananiam said. The majority of her patients with the most severe symptoms have been in their second or third trimester. Nearly all required preterm deliveries because they had to be intubated.

As of Aug. 14, 23.8 percent of pregnant people nationwide had received at least one dose of the vaccine — less than half the national rate of 51 percent.

A recent California study showed a 60-percent greater risk of miscarriage in COVID-positive pregnant women, said Jodie Dionne, associate director of UAB’s Global Health in the Center for Women’s Reproductive Health and an associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases.

Studies that have looked at the miscarriage rate in pregnant women who get the vaccine, including those who got it before reaching 20 weeks, have found no difference from the miscarriage rate in unvaccinated women.

As for the prospect of long-term side effects if a woman gets vaccinated while pregnant, Dionne said it’s important to know that side effects from vaccines are connected to when the vaccination occurs. Most appear in the first 24-48 hours after the shot, occasionally three to five days later and a small percentage within the first two weeks. After eight weeks, side effects don’t happen. Vaccines don’t work that way, Dionne said.

“It would not be consistent with all the rest of the vaccine data we have accumulated over decades to see a long-term, unexpected vaccine side effect after years from someone who had been vaccinated in the past. It just doesn’t fit with everything that we know about vaccines,” she said.

As a member of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine’s COVID-19 task force, Dionne said she repeatedly hears concerns about the vaccine causing infertility. It’s a pernicious rumor for which there is zero evidence, she said.

She challenged the notion that not enough is known about the vaccine because it or mRNA technology is new. Millions of dollars have been spent on trials and pregnant women have been included in studies, which is unique to this vaccine.

“We’re no longer in a place where we don’t have data. They have clear data in pregnant women of the safety of the vaccine. And again, balanced against that is the risk if you do come down with COVID-19 and all the short- and long-term outcomes of infection that we know are devastating,” she said.

Jessica Grayson, an assistant professor in the UAB Department of Otolaryngology, was 21 weeks pregnant in December when she received her first Pfizer shot. She made the decision as a mom and as a physician, she said, and because she wanted to protect her unborn baby and not risk leaving her two children without a mom. She also didn’t want to risk her oldest child suffering the guilt of potentially infecting her after bringing it home from school.

Her arm was sore afterward, but not enough to keep her from her CrossFit workout the next day. She got her second shot at 24 weeks. That caused a bit of a headache, she said, but nothing else. She enrolled in a program that tracked her and the baby’s experience through delivery. No concerns were raised throughout her pregnancy and she had a spontaneous delivery in April with no complications. Because she and her husband were vaccinated, she didn’t have to go through labor alone, and she felt safe accepting relatives in her home.

She also gets peace of mind from knowing that her 4-month-old son has her antibodies via transplacental transfer in utero and continues to receive them by breastfeeding, she said. She’s grateful that he has that protection until a vaccine is approved for young children.

Studies have shown that babies whose mothers were vaccinated with them in the womb have more antibodies than those who only receive them through breastmilk.

Williams said she recently had a virtual meeting with a pregnant patient who had decided to get the vaccine and made an appointment but then contracted the virus at an indoor family gathering. Her symptoms were relatively mild, but she told Williams she wished she’d gone for the vaccine sooner.

“And she said, you know, I wouldn’t wish this upon anybody,” Williams said.

She urged pregnant women who are unvaccinated and who have unvaccinated family members, especially a spouse or partner, to have a conversation with them about the risks and contagiousness of the delta variant and the vaccine’s ability to protect against it.

Grayson said that as a mom who’s been through it, her message to pregnant women is that they became moms the moment they found out they were pregnant, and they have already begun making the best decisions they know how to make to keep their babies safe.

“Mom-shaming runs rampant, especially with the advent of social media,” she said. “Shut those people out. You know, listen to your doctor. Listen to the physician that you are trusting to help you bring that baby into the world. Know that they are trying to help you heed the best advice to keep you and that baby safe.”