The letters kept showing up. A couple at first, then five or six more. By the time they stopped, Malinda Edwards had received between 30 to 40 handwritten notes, all of them from college students at the University of Alabama. Many of the students told Edwards that her father’s story — a horrific one of his murder and the subsequent miscarriages of justice that allowed his killers to remain free — had changed their lives, given them a new perspective on racism and racial harmony.

It was all a surprise to Edwards. Sure, she had spoken to the class at the UA Honors College as part of a podcast project the students were putting together, but she figured that was the end of it. The kids would finish the project, hopefully do the story justice and pass the class, and move on with their lives.

“I never expected letters,” Edwards said. “And I really didn’t expect to have these young people telling me that my father’s story had changed their lives. Here’s this young girl from Alabama telling me that (his story) had made her want to be a better person. The other letters said similar things. They were so nice and made me feel so good — they really gave me a lot of hope. It was like all that we did to bring attention to this story wasn’t for nothing.”

The story of Malinda Edwards’ father, Willie Edwards, is one of the most haunting atrocities of the Civil Rights era. Tortured by four members of the Ku Klux Klan, Willie Edwards was forced to jump from a bridge into the cold waters of the Alabama River on Jan. 23, 1957. His body was recovered by fishermen three months later.

Despite evidence, including the death bed confession of one of the participants and the testimony of another, none of Edwards’ murderers was ever held responsible. A judge tossed the case out in the mid-1970s, when then-Alabama Attorney General Bill Baxley tried to hold the four accountable. A grand jury failed to return an indictment in the late 1990s when Montgomery District Attorney Ellen Brooks tried again to get justice, although Malinda Edwards wonders still how hard Brooks really tried.

And so, three kids — Malinda and her sister and brother — grew up without their father. The murder left a young, Black woman with a family to feed at a time and in a place where good paying jobs for Black women were nonexistent. And it ended the life of a man who was, by all accounts, good and decent and hardworking and family oriented.

The complete failure of Alabama’s justice system to hold those responsible could fairly be chalked up to racism, ignorance and bias. And that’s why I contacted Malinda Edwards a few weeks ago — because I wanted to know how one of the key figures in one of America’s Civil Rights stories felt about the ongoing debate over “critical race theory” and the importance of teaching children an accurate American history.

What I expected to get from Malinda Edwards was a bitter, angry woman who would explain how America’s failure to tell true stories had allowed her father’s killers to walk free, to have families of their own, to experience the joys of life while she and her siblings and her mother had their pain and sorrow multiplied by the injustice of it all.

In short, what I expected from Malinda Edwards was anger. Instead, I found joy. And hope. And a whole lot of understanding.

I also found a lesson for everyone on how the truth doesn’t cause resentment and anger among young people — as so many rightwing critics of CRT and accurate American history claim — but instead inspires decency and a desire for better understanding.

“I think what (the Edwards’ family story) did for me was make Mr. Edwards human — the story, as we dug into it more and more, it made him so much more relatable to me,” said Mary Haddow, one of the students who spoke with Edwards for the class podcast. “(Willie Edwards) was at dinner with his family when his boss asked him if he wanted to pick up an extra shift and extra money. I could see my dad doing that. Trying to provide for his family, working hard, trying to move up. It made (Edwards) relatable and helped me to understand better the effect his death had on his family, how it mattered to real people.

“It changed me as a person. It really did. Seeing how racism and violence affects real people, it gave me a better understanding of other people. It helped me to relate better to the people at my job, my patients, my friends.”

For Haddow, the Edwards family went from being one-dimensional characters in a history book to three-dimensional real people, with feelings and life goals and hopes and dreams. A young family sitting around a dinner table, happy and hopeful one minute, destroyed by racism and hate forever.

The Murder

On that January day in 1957, when Willie Edwards was called away from dinner with his pregnant wife and two young daughters, he wanted only to be able to pay for their next meals, to get a tiny step up a small ladder at Winn Dixie, driving an extra delivery route late into the cold night.

When he returned from his route, the four Klansmen were waiting on him, convinced that he had said something inappropriate to a white woman. That’s all it took in 1957 Alabama, especially around Montgomery, where the Bus Boycott had ended a few months earlier and racial tensions were high.

The Klansmen — Henry Alexander, Raymond Britt, Sonny Kyle Livingston and Jimmy York — forced Willie into a car at gunpoint. They beat him and tortured him as they drove around. At one point, according to information provided by Britt, they threatened to castrate him if he didn’t admit to saying something inappropriate to the white woman. Finally, late in the night, they drove to the Tyler Goodwin Bridge, forced Willie out of the car and gave him two equally deadly choices: jump or take a bullet.

Willie jumped.

The case was closed quickly, even though the perpetrators were well-known hoodlums. Just 10 days earlier, Britt and Livingston had confessed to police that they were responsible for multiple bombings of Civil Rights leaders’ homes in Montgomery. They were indicted for the bombings and later acquitted by an all-white jury.

In 1976, with Baxley hounding him, Britt accepted an immunity deal: tell what happened to Willie Edwards and Baxley wouldn’t file charges against him. Britt named names and gave details. Baxley had a strong case, and he was pushing forward, despite threats and cries from some that he was simply opening long-closed wounds that wouldn’t help anyone.

But the judge on the case threw out the indictments of the four, ruling that Willie Edwards’ exact cause of death was never determined, and without an official homicide ruling by the medical examiner, murder charges against the defendants in the case couldn’t be proven. Making matters worse, Britt started to backtrack on some of his testimony. And to top it all off, FBI agents went to Baxley asking that he drop the case against Alexander, because Alexander was one of their best KKK informants.

Finally, Baxley, after years of fighting, gave up and dropped the case. But Malinda never did.

During the midst of Baxley’s prosecution, she quit her job in Buffalo and moved to Montgomery. “I just wanted to be close to it,” she told me. And kept it alive is what she did.

More than 20 years later, Malinda’s pushing would offer another break in the case: the state medical examiner in Montgomery agreed to examine Willie Edwards’ body if Brooks would have him exhumed. A few weeks later, his ruling was in: drowning. And the method of death was deemed a homicide.

Brooks expressed skepticism in the case but promised to put it before a grand jury and see if an indictment could be obtained. An indictment seemed like a sure thing, given the lopsided advantage that DAs enjoy when presenting to a grand jury (only the prosecution’s evidence and witnesses are presented) and the fact that one of the participants had admitted to the crime.

And one other thing: A second Klansman had confessed to the murder on his deathbed a few years earlier, according to his wife. Henry Alexander’s widow, Diane Alexander, had gone so far as to call Willie Edwards’ widow, Sarah Salter, in 1993 and relay the deathbed confession. Diane Alexander also apologized for her husband and said she wanted to make it right.

Somehow, it wasn’t enough. The grand jury refused to indict the old Klansmen. Malinda was angry.

“I didn’t speak to Ellen Brooks for a long time after that,” Edwards said. “Well, I said some things to her right after the grand jury, and then I didn’t speak to her for a long time. It was a tremendous letdown for me. It really weighed on me.”

Eventually, Malinda said, she spoke with Brooks and they keep in touch even today. She still isn’t sure about that grand jury process, but she’s moved on. The Edwards family has always been good at that.

After The Murder

Following the murder of her father, Malinda and her sister, Mildred, leaned heavily on their young mother, Sarah, and the rest of her family members in west Montgomery. For a young Black family in Montgomery in 1957, times were not easy. The city was just coming off the famous Bus Boycott and tension was high. Good paying jobs were scarce, and even more so for 23-year-old Black women.

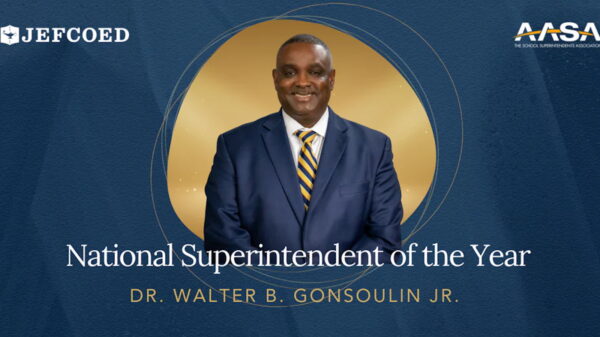

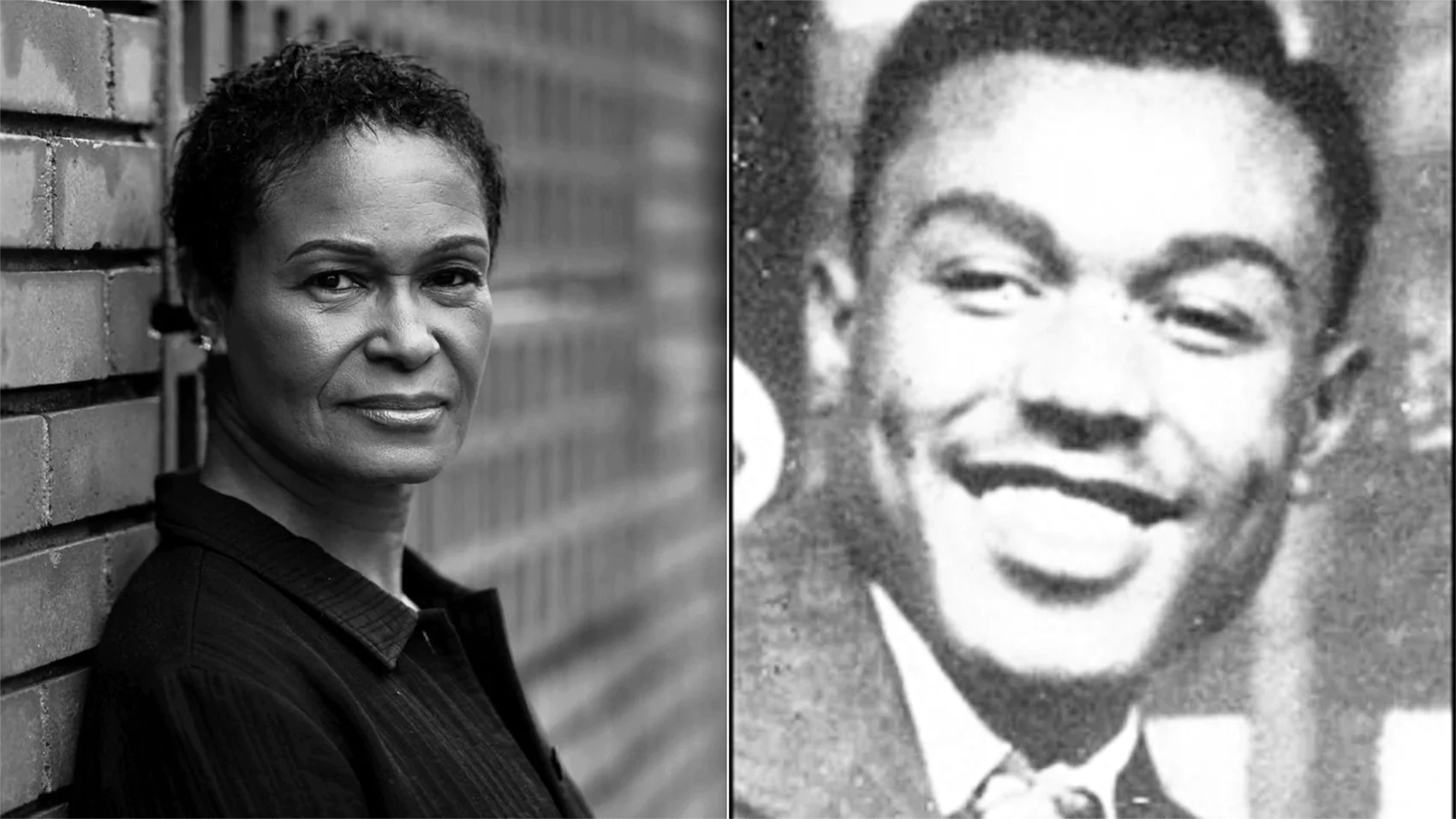

Willie’s widow, Sarah Salter

Sarah, however, could sew and she was considered a good hairdresser. Between those two jobs, and a handful of other odd jobs, and with family members and neighbors helping out, the Edwards family got by.

A few years after Willie’s murder, Sarah remarried, and the family moved to Buffalo where Malinda’s stepfather had taken a job with UPS. The move was a culture shock for the young family from Montgomery, and one that likely changed them for the better.

“We moved from this place where we wouldn’t look white people in the eyes — kids were taught to look down when addressing white people — and we moved to this place where that’s not how we behaved,” Malinda said. “We went to an all-white school for a while and never had a problem. We had white teachers and Black teachers. We lived in mixed-race neighborhoods. It truly transformed the way I thought about life.”

But most impactful on the young Edwards kids was the grace and compassion of their mother, who, despite the pain of having her husband killed by racist thugs, taught her children that hate based on skin color would not be tolerated in their house.

“She taught us that while white people were responsible for the murder of my father, not all white people were responsible,” Malinda said. “That’s how we grew up. We didn’t hate anyone. My best friend is white today, and we had numerous white friends growing up. That’s just the way we lived, and my mom would accept nothing less.”

The Class

Maybe it’s that grace instilled in Malinda Edwards by her mother that made such an impact on the students in Billy Field’s documentary production class at the University of Alabama’s Honors College. Whatever it was, it was unlike anything Field has ever seen.

“The students just really connected with this story and with her,” Field said. “It’s the sort of thing that you hope for as a teacher — that they’ll connect and something will make a difference for them. And this project did that. I think a lot of it had to do with how open (Malinda Edwards) was with them and the way they connected with her.

“It’s a tragic story. And I believe for a lot of the students, it was their first real encounter with the realities of what happened in that era — actually seeing how it affected a real person and a real family.”

That was certainly the case for Mary Haddow, who was a senior at the time. She took the class thinking it would be an easy A — a way to fill her elective requirements without adding more to her very full plate. It turned into the class that she’ll remember forever.

“It’s so hard to put into words what it meant to me,” Haddow said. “It’s a terrible story, and that poor family. It just changed the way I see things. It helped me to understand everyone around me so much more.”

That’s pretty much Field’s objective every semester — to put together class projects that inspire an emotional connection between the students, the subject and the audience. The class typically selects someone from the state of Alabama — a lesser-known figure, but one with an important story to tell — and then puts together a documentary film on that subject. There are dozens of documentaries on the department’s website, all of them shot by students.

“We had a student in class one year who mentioned in passing that he knew Martin Luther King Jr.’s barber and wondered if that would be a good subject,” Field said. “We’ve covered a lot of state history and important figures.”

Because of COVID-19 issues last year, the class was forced to change from a documentary film to a podcast. But they didn’t cut corners. The class took a deep dive into the murder and the Edwards family.

Field said he didn’t realize the enormous effect the project had on his students until a letter arrived a few weeks after the class from Haddow’s father. He wanted to thank Field and tell him how much the class had changed his daughter, had made her more understanding and compassionate.

“She … will pay it forward in some form or fashion,” Dan Haddow wrote. “She will be more humane, more understanding, more empathetic in her posture … she will look back at you, her classmates, and the experience you provided, in my opinion, and hopefully choose the right type of politics (distribution of power) where all are dignified. Thank you for teaching her a more refined dignity!”

She’s already paying. After graduating, Mary took a job as a child life specialist at a hospital, and she carried with her the lessons learned from that class — the empathy and understanding. It helps her, she said, to better understand the frustrations and anger of her minority patients, and more importantly, it gives her a pathway towards helping them deal with it and the illnesses they’re going through.

“A lot of times my patients have been through situations — whether it’s racism or some other situation — that I really can’t relate to,” she said. “I think what I learned from that project and from talks with Ms. Edwards is how to better recognize those situations and offer more understanding.”

Which, of course, is the goal of any decent history teacher — to offer an unvarnished view of history, warts and all, so we don’t repeat the mistakes of the past. So we can become better people, living in better societies, treating each other better.

Teaching students — from the earliest grades through college courses — an accurate history, particularly our history of racism and racist acts in this country, doesn’t inspire hatred and division. It lessens it. Because the overwhelming majority of people in this country want to be decent and good. They want to be considered kind and loving.

The only way to make sure they’re not is through lies and half-truths, by masking the real history and leading generations of Americans to believe that incarceration rates are somehow determined by skin pigmentation.

“An accurate history is the only thing that will pull us together,” said Field. “It’s that understanding that means so much to our cohesiveness as a nation. Without the understanding, we can’t get to the compassion for one another. It’s that simple.”