Those concerned about a bill that would strip away some oversight from public K-12 school construction and repair projects once again voiced those concerns at a meeting Tuesday of a study group tasked with working on the legislation.

An amended House Bill 220, approved by the state Legislature in May, will remove state oversight by the Alabama Department of Finance’s Division of Construction Management (DCM) for construction and repair projects under $500,000 at K-12 schools, universities and state parks. It also takes all roof and HVAC repairs and maintenance projects out from under DCM’s oversight.

Gov. Kay Ivey sent an amended version of the bill to lawmakers prior to its passage, which delays the law’s impact on K-12 schools until Feb. 1, 2022, and also set up the study group and tasked members with addressing concerns expressed during prior debates on the bill.

A letter opposing the bill was signed by the Alabama Associated General Contractors, Associated Builders and Contractors of Alabama, Subcontractors Association of Alabama, American Institute of Architects Alabama and the Alabama Contractors Association.

Among those with concerns is Tim Love, president of the Alabama Association of Fire Chiefs and chief of the Alabaster Fire Department, who is a member of the study group.

Love said during Tuesday’s meeting that there remains concern that removing oversight could lead to safety problems for school staff, students and first responders who have to enter buildings during emergencies.

Ryan Hollingsworth, executive director of the School Superintendents of Alabama, asked the group to consider raising the law’s $500,000 cap to $750,000 because of recent construction material cost increases.

“There can be a lot of catastrophic events associated with even a $25,000 capitol project or improvement at a school,” Love said, adding they’d rather lower the $500,000 figure but certainly are against raising it.

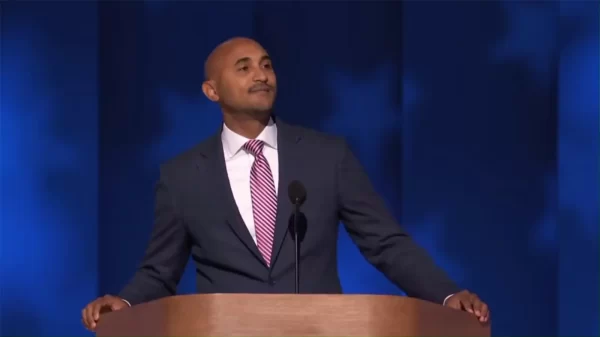

Rep. Nathaniel Ledbetter, R-Rainsville, who introduced HB220, was elected chairman of the study group at the start of the meeting. Ledbetter told APR in April that he drafted the bill after Dekalb County Schools Superintendent Jason Barnett approached him with concerns about costly, time-consuming construction projects.

Barnett, speaking to APR in April, was hesitant to answer why DCM stopped work on a gym’s roof repair, when asked if it was due to non-compliance with codes, but eventually said “not that I’m aware of.”

Love told APR at the time that he’d heard about that gym project that Barnett was concerned about, and so he called DMC to learn more, and was told it was due to code compliance on the old building.

Rep. Donnie Chasteen, R-Geneva, who was elected vice-chair of the study group, said during the meeting that as legislators they’ve received calls from those in the education community about “issues with the Department of Construction Management, as far as the cost and time.”

Chasteen said a small high school had a budget of approximately $150,000 for upgrades to a science lab, but after DCM reviewed the plans and recommended changes, the cost increased to $350,000.

“While they may have been blamed for making a project go from $100,000 to $350,000 they do not,” said study group member Heather Page with Whorton Engineering, and president-elect of the American Council of Engineering Companies of Alabama. “It is the designers. We are the ones who design it. We are expected to give the owners a realistic scope budget, and it is our responsibility to design to the applicable code.”

Allen Harris, CEO of Bailey-Harris Construction and a study group member, said cost increases on school projects are often the result of an older school building needing to meet changing construction codes.

“The last 10 years and 15 years they’ve changed immensely,” Harris said of the state’s construction codes. “DCM just simply makes sure that all those codes are included.”

John Montgomery, Gov. Ivey’s appointee to the study group and general counsel for the Alabama Department of Finance, said while there are some school construction projects that take longer than others for DCM to review, records show the department has a short turnaround time for the majority.

“Over the last five years, DCM has reviewed 8,068 plans and an average of 6.43 calendar days. On average, there’s less than a week turnaround on DCM’s plan review for code compliance,” Montgomery said.

Love said his association’s biggest concern is about who will be tasked with inspecting public school construction projects once DCM will no longer be providing that oversight.

“Counties and municipalities, currently they do not have the authority to perform such inspections and enforce the codes, so who would enforce that code?” Love asked, adding that many counties do not have building departments.

An attorney on the committee, who wasn’t identified during the meeting, replied that the bill doesn’t dictate who would do those inspections, but that it gives the Alabama Department of Education the task of deciding those details, adding that local school boards could decide to use DCM.

“One thing the bill does do, it requires the architects that’s on site to inspect it periodically,” Ledbetter said.

The bill’s language does not, however, require architects to make periodic inspections of projects they themselves are paid to design. The unidentified attorney who spoke earlier later addressed that fact.

“Again, the bill does not specifically say who would be the final party conducting the property inspections under the new regulatory scheme,” the attorney said. “That would be up to whatever standardized process the Department of Education comes out with, in whatever forms they supply, whatever checklists they give the local boards of education to comply with in the construction projects.”

Chuck Ledbetter, a district president with School Superintendents of Alabama, told the members that nobody wants to cut corners when it comes to safety.

“I think I speak for all the school superintendents in saying that that’s not the issue. The issue is making sure that we safely do things in a timely fashion so that we can use taxpayer money to the best for our students,” Ledbetter said.

Harris said of the states he and the other study group members reviewed, all had some kind of independent oversight of school construction projects.

“Because we’re all human, and they know it and we know it. My people are as good as they come, and we insist on quality work…whatever you do in Alabama is quality, but we make mistakes,” Harris said. “And so, as he said, when BCM inspectors come it’s a help to us.”

Love told ARP after the meeting that he was surprised to hear the request to raise the cap from $500,000 to $750,000. That request hadn’t been discussed between members prior to Tuesday’s meeting, he said.

He again expressed concern that the law doesn’t specify who will be changed with inspecting school construction projects to ensure code compliance.

“I couldn’t figure out why they couldn’t answer that question,” Love said, adding that it shouldn’t be the same architects who are working on those projects, and that it should be an independent review.

“We just want to ensure safety, and I just don’t feel we’re getting a good solid answer on how we’re going to make that happen,” Love said.

The committee is set to meet again on July 19 to hold a public hearing. Ivey’s amendments require the study group to report its findings and any legislative recommendations to Ivey, House and Senate leadership by Dec. 1, 2021.