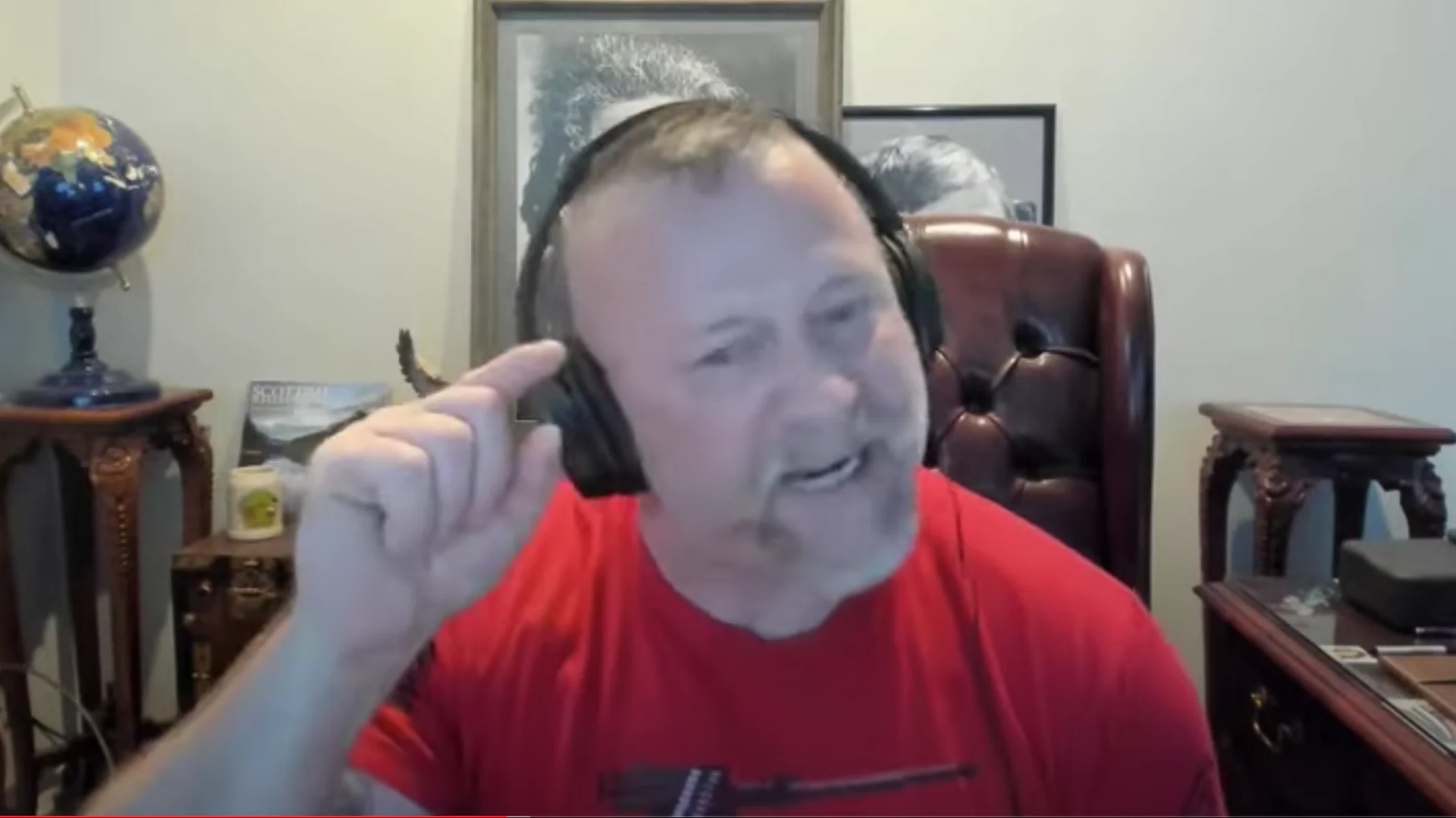

Richard Ojeda is a hard-nosed retired Army officer, former West Virginia state senator and podcast host looking for Democrats to run for Congress, and he’s looking for Alabamians who can fight the state’s Republican representatives in Washington.

“At the end of the day, millionaires ain’t doing jack s— but padding their pockets and crawling in bed with ALEC and all these other organizations,” Ojeda said. “Nobody has the balls to stand up to Big Pharma or Big Energy, and that’s how it is.”

He got louder and more profane as he described politicians who claim to fight for the state’s residents yet contribute little to nothing to, or outright oppose, legislation that improves the lives of the average voter.

It’s a pattern he came to know intimately in West Virginia, he said. He sees Alabama voters the same way — betrayed by entrenched leaders who claim to be cut from the same cloth but who, once elected, ignore or oppose action that would address the biggest problems facing the people who elected them.

This was epitomized for him by a visit President Donald Trump made to West Virginia to support Ojeda’s Republican opponent for a House seat in 2018. Trump wore a hardhat and feigned a shoveling motion in front of a crowd of coal workers.

The Republican, Carol Miller, defeated Ojeda 56 to 43 percent, a comparatively narrow margin in a state that went for Trump in 2016 by 69 percent to Hillary Clinton’s 26.

Ojeda was one of those Trump voters in 2016, though only because he hated that the Democrats nominated Clinton instead of Bernie Sanders.

When he retired at the rank of major after 24 years in the Army, Ojeda returned home and noticed how different his local elected leaders were from the military leadership he was used to; the kind that led from the front and fought in service of the mission’s objectives rather than self-interest.

“I’m finding that everybody had their hands in the cookie jar. Nobody was a real leader,” Ojeda said. “And controlling elections — I mean, literally things that took place back in the ‘50s in elections in this country are still taking place today. I’m talking about literally passing out bottles of friggin’ liquor on Election Day and handing out gift cards for $20 each to everybody when they finished voting.”

He was elected to the state senate in 2016, beating the Republican with 59 percent of the vote. He was one of six Democrats who won races for that chamber. Republicans won 12. Among the accomplishments he touts most during his single term was his early support for the 2018 teachers’ strike that gained national attention, won a pay raise and inspired similar strikes in other states.

He launched a few other candidacies for national office, including a bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, but was defeated in each. He partly blames the national Democratic Party establishment for his campaigns dying on the vine, as he says. They only supported his House run after Sen. Joe Manchin vouched for his viability and urged them to, he said.

Ojeda’s political activity targets Republicans, but he rails against the insider culture of establishment power structures across the board.

“The Democratic Party didn’t want me,” he said. “The reason why is because the Democratic Party knows they can’t look at me and say, hey, excuse me, you need to vote yes, yes, yes, no, no, yes, yes — ’cause I’m going to tell them to f— off. Because at the end of the day, I’m going to vote the way I believe is best for my people, and that ain’t got jack s— to do with what anybody else in Washington, D.C.’s got to say.”

Still, he says, he was able to cut into his opponent’s lead significantly in 2018 despite Trump’s campaigning for her. Like Sen. Tommy Tuberville two years later, she refused to participate in debates or take questions from reporters about her platform.

Why does Alabama only send its absolute worst to represent them in Washington? @SenTuberville @MoBrooks that other guy that stalked 12 year olds at the mall, and rode around on a horse.

We at @NoDemLeftBehind are looking for solid candidates to support in Alabama tag below 👇🏼— Richard N. Ojeda, II (@Ojeda4America) April 7, 2021

The issue of most concern to the district’s voters at that time was the caravan of migrants approaching the country’s southern border, Ojeda said. Despite widespread poverty and the severity of threats like the opioid epidemic, voters were focused on an issue that would have little to no direct impact on their lives.

“And that’s the same s— that you guys are dealing with in Alabama, and we got to find people that can actually relate to people on both sides,” Ojeda said.

He and a small team run No Dem Left Behind, an organization that aims to get rural Democrats elected in red districts. They do the kind of candidate scouting, recruitment, training and support that the group Justice Democrats did to identify Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and get her elected in New York.

Ojeda’s group, however, has to strategize very differently for a much harder mission.

“It’s so easy for these organizations that are out there that, you know, are only running in the blue states. It’s easy for you to say, ‘Look how successful we are, we got this person, this person, this person,’” he said.

No Dem Left Behind supported 17 candidates in 2020. None of them won. What’s significant, Ojeda says, is that they were inspiring candidates who garnered 30-35 percent of votes in red districts. It only takes 51 percent to win, he noted.

One such candidate was Lindsey Simmons, an attorney and military spouse with a degree from Harvard Law School. She lost her House race in Missouri to Republican incumbent Vicky Hartzler, who won 68 percent of the vote in a mostly rural district that flipped red in the 2010 midterms and has remained conservative.

Ojeda sees efforts like hers, although unsuccessful at winning the seat, as successful at ushering young, smart and qualified candidates into politics in places that the Democratic Party has written off and stopped trying to reach voters. Running quality candidates in these places is an essential first step in creating the grassroots movement required to change the dynamic, he argues.

Rural voters in the South are patriotic, so people with military experience are especially suited to appeal to them, he said. They also often bring skills needed to cut through the partisan polarity and culture war talking points.

“You want to get somebody who knows how to speak to people? You go find a sergeant major, you go find a retired lieutenant colonel or above, because they know how to speak to people,” Ojeda said.

Military service is not a requirement, however. Ojeda simply wants to find intelligent people who are willing to fight. By fight, he means committed campaigning and outreach, and doing things like filing Freedom of Information Act requests at their local courthouses to expose incumbents’ shady financial dealings, or whatever else might be discovered.

No Dem Left Behind has formed a political action committee and is focusing on fundraising. While they want to identify, follow and potentially mentor good candidates, their campaigns have petered out when they ran out of money.

In the meantime, Ojeda uses his active social media presence to advocate for his strategy. He publishes his podcast, Airborne, on YouTube, where he has interviewed guests like Andrew Yang and Ice T.

That’s how to reach voters of any persuasion, he says — engage directly with them on social media. Answer their questions. Have conversations.

His group wants to eventually have House candidates in all 50 states. So far, Alabama is one of the states where they’re currently looking to build relationships.

“We want some people in Alabama to reach out to us and say look, this person could run for Congress,” Ojeda said.