Gov. Kay Ivey on Friday signed several criminal justice reform bills into law, some products of Ivey’s criminal justice study group, which was formed to draft legislation aimed at resolving Alabama’s longstanding and deadly prison crisis.

While the study group’s recommendations, released in January 2020, did include suggestions on spending and ways to reduce recidivism, the group declined to take up more substantive sentencing reform measures.

The state is facing a lawsuit filed by the U.S. Department of Justice over Alabama’s deadly, overpopulated and understaffed prisons, and the threat of possible federal oversight of Alabama’s prisons still looms.

“Criminal justice reform is not only necessary, but is a top priority of my Administration. I am proud to sign these bills into law as we work to prepare inmates to reenter society as productive citizens,” Ivey said in a statement.

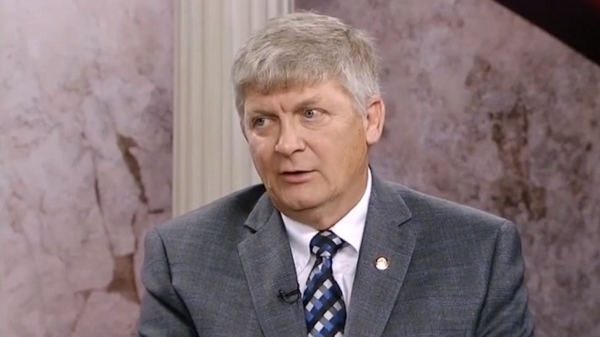

Study group member Rep. Chris England, D-Tuscaloosa, introduced House Bill 106, a revision of a similar bill he filed the previous year, which requires the Alabama Department of Corrections to report quarterly to a legislative oversight committee with information on violent offenses occurring in prisons, staffing numbers and state money paid toward lawsuits against the department.

ADOC has been criticized by some lawmakers and the U.S. Department of Justice over a lack of transparency. In an amended complaint filed Wednesday, the DOJ stated ADOC fails to accurately report homicides and serious assaults.

Another bill by England, which would have repealed the state’s Habitual Felony Offender Act — seen by reform advocates as an antiquated sentencing law that sends far too many people to lengthy prison sentences — passed the House Judiciary Committee but never made it to the House floor for a vote. The bill faced opposition from some Republican lawmakers.

Ivey’s criminal justice study group declined to take up legislation to repeal the state’s Habitual Felony Offender Act. England, citing the need to address the state’s strict sentencing laws and overpopulated prisons, drafted the legislation on his own.

Alabama prisons rank fourth-highest in the nation for the percentage of incarcerated people who are serving either life without the possibility of parole, life with the possibility of parole or sentences of at least 50 years, according to a February report by The Sentencing Project.

Of the state’s 22,896 inmates, 502 were serving life without the possibility of parole under the Habitual Felony Offender Act, according to the Alabama Department of Corrections’ latest monthly report. The law also increases sentences for thousands more in Alabama’s prisons, with 21 percent of all convicted under the law serving 20-year sentences.

The DOJ’s lawsuit against Alabama and the ADOC alleges violations of incarcerated men’s constitutional rights to protection from prisoner-on-prisoner violence, sexual abuse and excessive force by prison guards. The federal government says Alabama’s prisons are far too overpopulated and understaffed, which is driving much of the violence.

Ivey also signed into law Senate Bill 221 by Rep. Clyde Chambliss, R-Prattville, which creates the position of Deputy Commissioner of Prison Rehabilitation within ADOC and the position of Deputy Director for Parolee Rehabilitation within the Alabama Bureau of Pardons and Paroles.

That bill also creates the Study Commission on Interagency Cooperation and Collaboration on the Rehabilitation and Reintegration of Formerly Incarcerated Individuals. Chambliss’s bill aims to refocus those state agencies on reducing recidivism.

Ivey also signed Chambliss’s Senate Bill 323, which reduces prison sentences by up to one year for incarcerated people who complete academic and vocational programs while in prison. People convicted of a Class A or Class B felony, and those convicted of a sex crime, aren’t eligible under this law.

Also signed by Ivey on Friday was House Bill 137 Rep. Chip Brown, R-Mobile, which creates the Sexual Assault Task Force tasked with implementing policies developed by the DOJ related to care and treatment of sexual assault survivors and the preservation of forensic evidence.

Brown’s bill also makes clear that a sexual assault survivor has the right to a free forensic medical exam whether or not the person cooperates with law enforcement related to the assault. The law also mandates that evidence kits be preserved for at least 20 years, or until the victim turns 40, if the victim was a minor when the assault occurred.