Huntsville police officers were found to have admitted to violating their department’s policies regarding use of less-lethal munitions during protests against police brutality last June, an attorney told the Huntsville City Council Thursday.

The city’s long-awaited report involved reviewing hundreds of hours of body camera footage, which in several instances contradicted testimony given by Police Chief Mark McMurray about police actions on June 3.

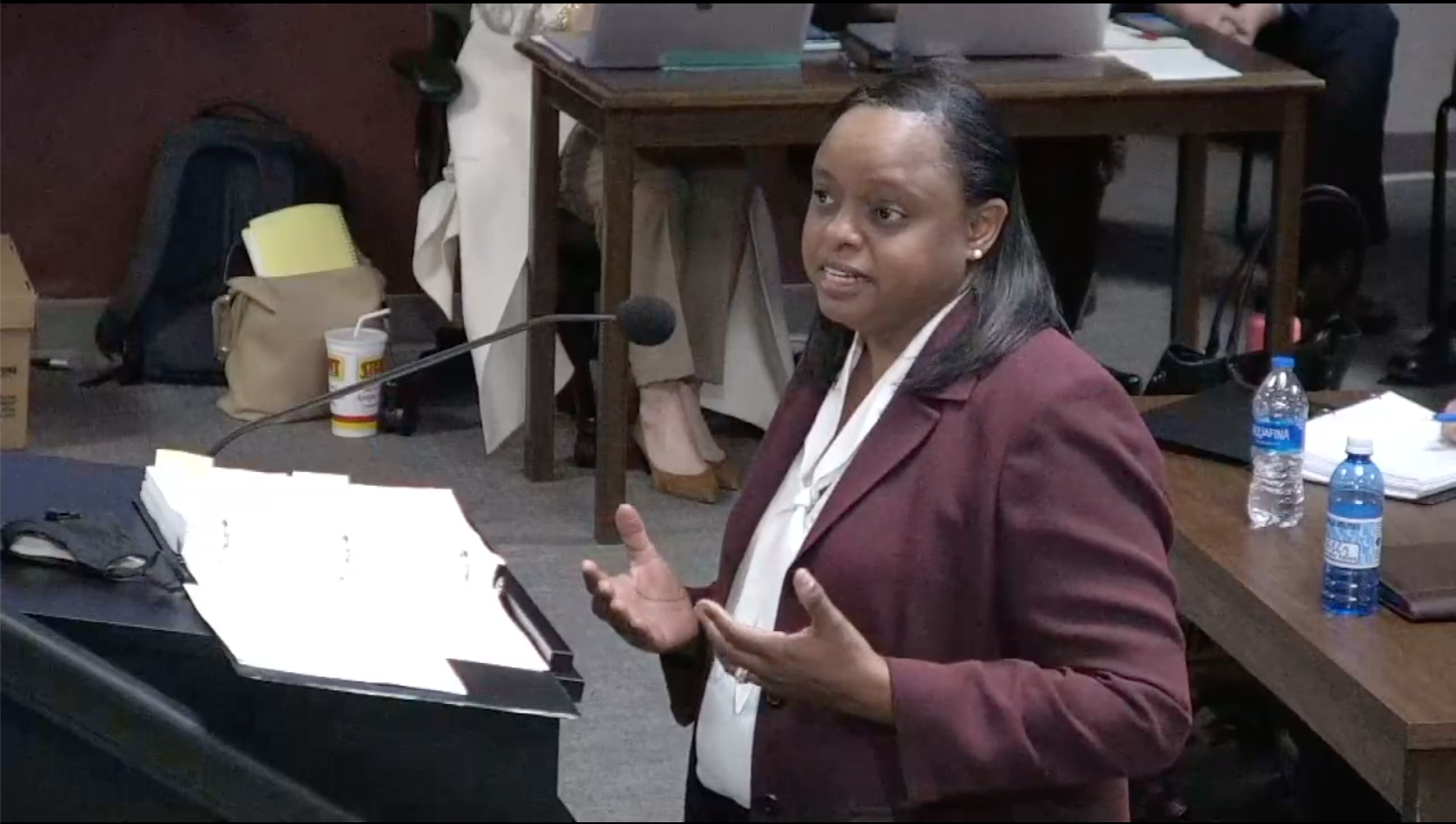

Speaking on behalf of the Huntsville Police Citizens Advisory Council, independent counsel Elizabeth Huntley said an officer was heard on body camera footage saying that he shot someone in the face with a beanbag round, which goes against HPD’s directives on the use of such rounds.

HPD officers shot a significant number of beanbag rounds, Huntley said, but the HPCAC did not know under what circumstances they were used and whether they were deployed according to department rules because HPD did not allow any officers other than McMurray to be interviewed and did not turn over any training records for its less-lethal munitions.

Another officer was heard on body camera footage saying that he had fired five “rubberized fin rounds,” Huntley said. McMurray didn’t mention any such rounds in his after-action report to city leaders, and HPD has never made public its inventory of less-lethal munitions. Huntley said that without interviewing the officer or seeing clear video footage, the HPCAC was unable to learn any more about that instance.

“All we know is that he stated it on his body camera footage and it’s our responsibility to tell the facts. And that is a fact,” she said.

Most protesters who suffered injuries have attributed their open wounds and welts to rubber bullets — called kinetic impact rounds in munitions parlance — but McMurray has stated publicly and to the HPCAC that he never authorized their use on June 3. He has said his department does not have them, but he has never said which agency did. Madison County Sheriff’s Office deputies were widely believed to have used them, although the agency ignored inquiries about it. Huntley said the evidence confirms that.

She added that there was no reason to doubt McMurray’s claims but said the disconnect creates “a question about internal control and creates a question about knowledge of inventory and oversight.”

Another policy violation was the pointing of sniper rifles at demonstrators from the roof of the Madison County Courthouse by county sheriff’s deputies and Madison Police Department officers. They were under McMurray’s command, and HPD guidelines dictate that binoculars should be used to monitor crowds rather than rifle scopes.

The report also found fault with how officers used pepper spray against protesters who have claimed it was used aggressively and recklessly. Huntley said there were instances of officers using it that were “at a minimum unprofessional and on multiple occasions in violation of HPD policy.”

Huntley noted that body cameras recorded officers at the scene saying they weren’t trained for what was happening. She described the situation as unique because on some level, police represented what demonstrators were protesting. Instead of passive peacekeepers, they became targets of protesters’ frustration and anger.

Some senior officers were heard on footage encouraging their colleagues to keep a “thick skin” as some people in the crowd yelled at or goaded them. There were also officers caught on tape saying “inappropriate things about the nature of the protest.”

Huntley suggested that any response to a dynamic like that needs to be tailored to it.

“And therefore that calls for a different level of training, maybe a different thought approach to how one might engage in a protest of that content,” she said. “This is a smart city. Y’all want to know — I’m telling you.”

She contrasted HPD’s approach with how the Birmingham Police Department handled a 1992 march by white supremacists through the predominantly Black city’s downtown. Johnnie Johnson Jr., the city’s first Black police chief, had someone from his predominantly Black department contact the march organizers in advance. They communicated about every detail of the event, from where the marchers would park to what the manner of the demonstration would be and where it would go. In the end, only three arrests were made of counter-protesters and there was no violence.

That kind of communication was lacking prior to and during the events of last June, Huntley said. Information about what was being planned, which police largely gleaned from social media, was not used to make contact with organizers and communicate about what was about to take place. Instead, it amplified police concerns about what might take place.

At the conclusion of the peaceful NAACP rally — the permit timeline for which had been changed, unknown to many — HPD ordered the crowd to disperse over a loudspeaker that wasn’t loud enough for everyone to hear, which McMurray acknowledged, Huntley said. It created a situation where people who were unaware of what was happening were suddenly treated as non-compliant.

Council President Jennie Robinson said it appeared that communication was at the heart of the problem.

Concerned residents in attendance, by now familiar faces at council meetings, expressed familiar frustrations about apparent satisfaction with and deference granted to HPD by council members. Local activist Reemuhlus Bowden challenged the suggestion that police were simply not communicating enough last June. He asked how the council could not have been aware that officers weren’t being allowed to be interviewed for the investigation it commissioned. He questioned why McMurray is still chief of police.

“Not only that, we’re praising him for his lack of communication,” Bowden said. “If you ask him — ‘It wasn’t me, it wasn’t the HPD, we didn’t shoot this, we didn’t do that, we didn’t do this so we really have nothing to do with this.”

Council Member Devyn Keith asked whether disciplinary action had been taken against any HPD officers for misconduct on June 1 or 3. HPD did not report any to the HPCAC, Huntley said.

The City Council will discuss proposals for reform at its next meeting April 29.