The safety of Alabama students and first responders will be at risk if legislation that would remove a critical layer of oversight for school construction projects is approved, according to architects and fire chiefs opposed to the bill.

Current law mandates that new construction and renovations of K-12, 2-year and community colleges must be plan-reviewed and inspected by the Alabama Department of Finance’s Division of Construction Management.

House Bill 220, which was approved by the House and a Senate committee, and awaits a vote in the full Senate, would remove that oversight, and instead leave that responsibility to the local governing boards of those institutions for all construction and repair projects under $500,000.

Tim love, president of the Alabama Association of Fire Chiefs and chief of the Alabaster Fire Department, told APR on Friday that the lives of those inside school buildings, and the first responders who have to enter them in emergencies, would be put at risk if the bill passes.

“It’s really really disheartening, because this is a very critical safety issue for the future of building of educational facilities,” Love said of the House and Senate committee approvals.

Love said that until last year he oversaw Alabaster’s building department, and said without that extra level of oversight there are bound to be problem projects.

“You will not believe the number of plans that we get that are stamped by professional engineers, architects, and they’ve done really good work but we found deficiency in code compliance,” Love said. “That’s what oversight does for you. It makes sure that you’re safe.”

“That’s our top concern, from the firefighter standpoint, is that we build safe buildings. We have safe builds for our kids and then for our responders who have to go into these buildings,” Love said.

“If this passes, today what’s it going to do? Nothing, but five years down the road, we have that collapse, or we have that fire, that the system is inappropriate, or there’s been some renegade alterations in a building, because there’s nobody that says you got to do any follow ups,” Love said. “And then we had that catastrophic event. How’s going to be at fault at that point?”

Love said we’ll end up with injured or killed children and firefighters “because we’ve got a poorly designed, non-inspected building, and there’s no reason for this.”

“We cannot see why they would introduce such legislation. This is going to end up in tragedy,” Love said.

There are counties in Alabama that do not have building departments with inspectors to oversee construction projects, Love said, but at least current law makes certain that oversight happens for schools even in those counties through the Division of Construction management.

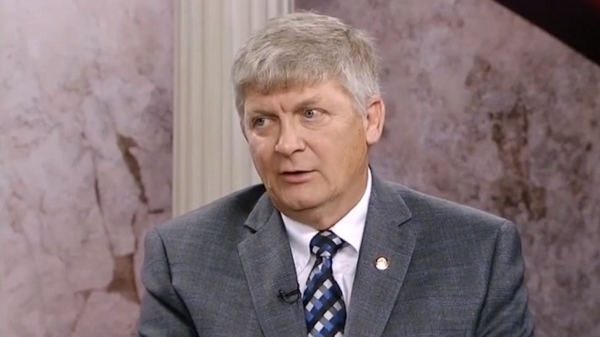

Attempts Friday to reach Rep. Nathaniel Ledbetter, R-Rainsville, who introduced HB220, were unsuccessful. Love said that he spoke to Ledbetter about the bill, and was told of a school roof repair project that went from an estimated cost of $30,000 to approximately $200,000 after the Division of Construction management provided oversight.

Love contacted the Division of Construction Management to ask about that project, and learned that the old school building’s roof needed upgrading to meet current code.

Anthony Clifton, director of the Dekalb County Emergency Management Agency, told APR that a staff member at his county’s school system decided to install fencing around all of the schools, which concerned Clifton, because while it may sound like a good safety measure, people with bad intent can padlock those fences once inside, trapping the children in and slowing first responders’ access.

“You can’t get in. You can’t get out. That is not a good situation to have,” Clifton said. He learned that the Division of Construction Management is tasked with overseeing such school construction projects, and reached out to the department, which wasn’t notified of the fencing plans, to discuss his concerns.

“Spent a half-million dollars of the school board’s money and actually made things worse than what he intended to try to fix,” Clifton said.

“That’s one of the projects that they failed to that they fail to meet standards on,” Clifton said of the school system. “If this bill passes there will be nobody for me left to turn to.”

Rep. Ledbetter represents his county, Clifton said, and he suspects the school fencing matter is a part of how this legislation came to be.

Scott Williams, a Montgomery architect with 50 years of experience, 35 of which at his own firm, told APR on Friday that he’s extremely concerned of what could happen if the bill becomes law.

“They’re the gatekeepers that represent the public’s best interest,” Williams said of the Division of Construction management.

“If they’re going to do this, who is going to review this for code compliance?” Williams said. Proponents of the bill say architects themselves can ensure a project is up to code, but Williams says leaving it solely to architects would remove an important level of oversight.

“If I were perfect I would take that position, but I’m not. No architect is. They are a valued second opinion at the same peer level as architects,” Williams said of the Division of Construction Management. “There’s a gazillion parts and pieces to a building, and all of it has to be assembled so that you have this coherent system, which is safe and occupiable and comfortable.”

Williams said not only does the state department ensure plans are up to code, but the department also makes certain projects stay within competitive bid laws, and that insurances and bond matters are properly handled.

“Even the local owner has a better assurance that they’re going to get what they asked for, at a quality level that meets all the standards that are normal and customary,” Williams said.

Williams said he understands those who support this legislation say the Division of Construction Management slows down project timelines, but he disagreed.

“DCM doesn’t waste any time. They’re very, very efficient,” he said, referring to the department.

Asked if local school boards are equipped to provide that same level of professional oversight, William said no.

“To my knowledge, none of them are. They’ve got some good facility staff, but they’re not versed in all of this, and they don’t really understand how the documents thread together to make a nice package that’s coherent for the contractors to bid on,” Williams said.

Williams spoke to legislators at hearings for this bill in committees in both the House and Senate, and said no lawmaker asked him questions after he spoke of his concerns. That lack of apparent interest concerned him, he said.

Williams said these projects expend enormous amounts of the public’s money, and architects working with the Division of Construction Management, are trying to work in the best interest of the public.

“And they ought to appreciate that,” Williams said. He’s concerned that the public’s best interest is not at the center of this legislation. “If something goes wrong, the rest of us have to pick it up and put it back together.”