According to historical documents, the Hopi Indians of America’s Southwest began burning coal for fuel in the early 1300s for “baking pottery, cooking food, and heating homes.” Now, a Native-American tribe in southern Alabama finds itself in the middle of a debate over the removal of coal ash from Plant Barry in southwest Alabama, about 25 miles north of Mobile.

Plant Barry has been in operation for over 60 years. Alabama Power is seeking permission from the Alabama Department of Environment Management to cap-in-place coal ash generated by the plant over many years, but the environment group Mobile Baykeeper wants the residue to be removed and relocated to a landfill.

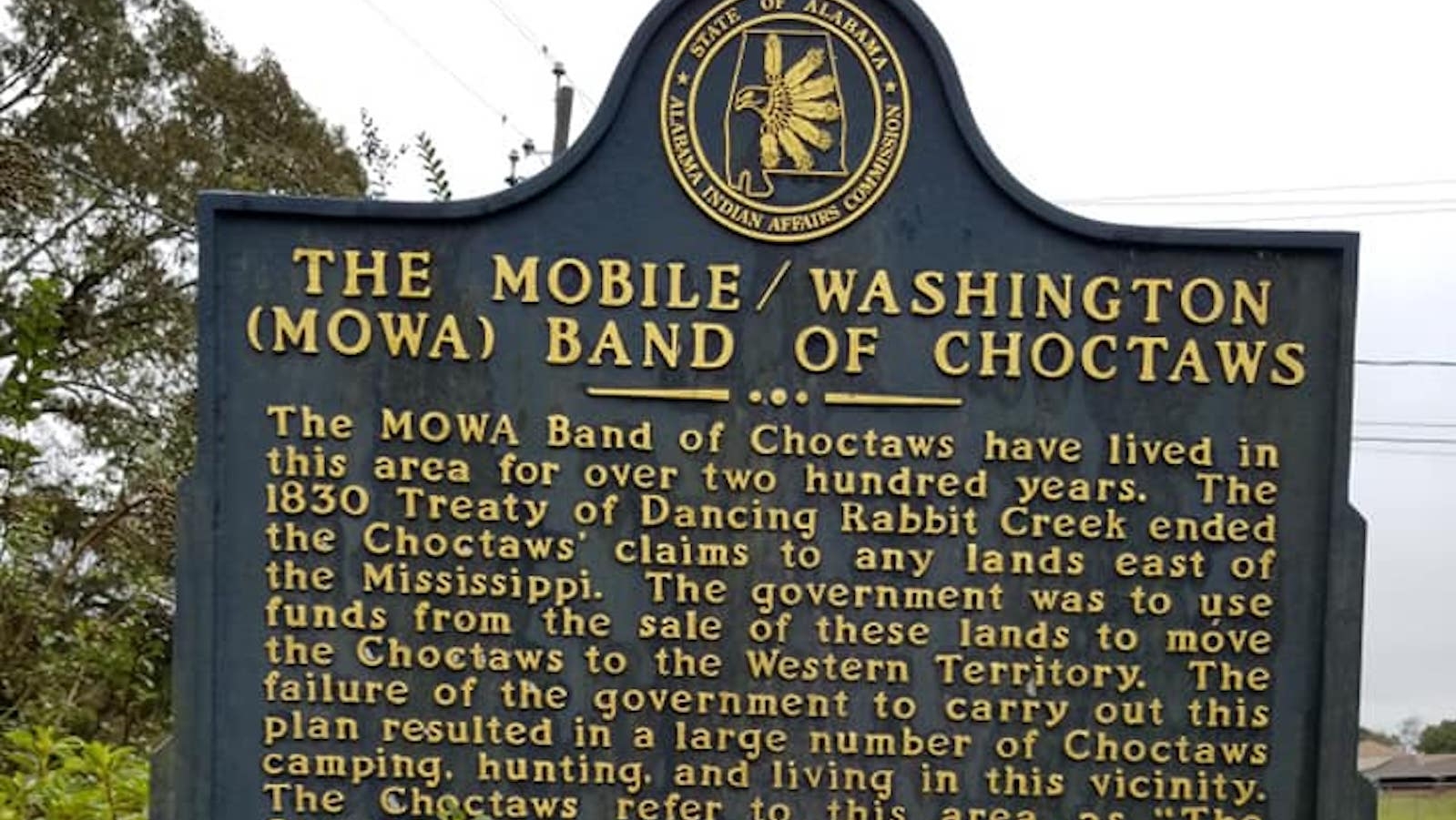

The MOWA Band of Choctaw Indians, a state-recognized tribe whose reservation is located along the banks of the Mobile and Tombigbee rivers near the small southwestern Alabama communities of McIntosh, Mount Vernon and Citronelle, and north of Mobile, are against the removal of the coal residue as it would likely be trucked through tribal communities.

Tribal Chief Dr. Lebaron Byrd said that the tribe has made its concerns known to state lawmakers as well as the power company: “We have made it clear that the tribe is in favor of it [coal ash] staying right there on-site and not being transported through our communities.”

In a February press release, Mobile Baykeeper said it had spent more than six years researching and investigating the coal-ash pond at Plant Barry: “Our research has consistently pointed toward one solution: the removal of coal ash to upland lined landfills and/or the recycling of the coal ash into concrete.”

Byrd says he is aware the environmental organizations are campaigning to have the coal ash removed to a landfill, but the Baykeeper organization and its members have never spoken with the tribe. “I know they [Baykeeper] wanted it moved, but they haven’t talked to us about how it affects us,” Byrd said.

Baykeeper estimates that coal ash removal of “Plant Barry’s 21 million tons of coal ash cannot be removed in the 15-year timeframe allotted under the CCR rule. However, they note other power providers have started the process knowing the process will run out of time.”

With 21 million cubic yards of coal ash to be removed, it is estimated that 2 million truckloads of coal ash would pass through the MOWA community if the removal option is executed.

“So we’re not talking about just three months or a six months project,” said Byrd. “We are talking about years.”

Currently, two landfills are the most logical locations if the coal ash is transported away from Plant Barry: Waste Management Chastang and Advanced Disposal Turkey Trot in Mt. Vernon. The area surrounding Mt. Vernon is heavily populated by the 6,000 members of the MOWA Choctaw tribe. Two sites along the route, Calcedeaver Elementary School and St. Theresa Catholic Church, are majority native institutions.

Casi Callaway, executive director of Mobile Baykeeper, in the February press release, said: “The community needs to speak up and demand Alabama Power and our environmental agency do the right thing – move the ash.”

Alabama’s Native-Americans don’t use coal like their ancient cousins but neither do they want it trucked through their homeland.

Byrd said the tribe’s views will be represented at the upcoming ADEM hearing, and that they will make their voices heard.

Still the MOWA Native American tribe is wondering why they are being left out of the equation by Baykeeper.

ADEM will hold a public hearing on Plant Barry Tuesday, March 30, at 6 p.m. at the Hampton Inn in Saraland.