Thirty years ago, the world seemed like a more stable place. The United States was at the height of international prowess and had deftly negotiated with almost the entire world to oust Saddam Hussein from Kuwait. President George H.W. Bush and his foreign policy team had built an international coalition to acknowledge that aggression against another sovereign state would not be tolerated. Even those countries that did not physically participate in the military coalition agreed to refrain from public dissent and allow the United Nations to live up to its charter.

The United States did not engage in appeasement or unilateral military action but initiated a precedent-setting effort that used international resolutions to express the world’s outrage. But unlike most UN resolutions, which aren’t worth the paper they are printed upon, the United States simultaneously organized a global military effort to give teeth to the resolutions.

At the same time, in another part of the world, East and West Germany unified. Long the focal point of Cold War tensions, the two Germanys agreed to combine and become a single country. This, too, was no small feat and required a significant amount of fancy footwork to make sure reunification didn’t ruffle the feathers of friend or foe.

A few NATO allies were not at all excited about a unified Germany and its impact on the balance of power in Europe; and, for obvious reasons, several Warsaw Pact allies shared similar concerns. But once, Russia, the 800-pound gorilla of the Warsaw Pact, gave its blessing, reunification could officially begin. Inasmuch as reuniting Germany was akin to the final prisoner exchange at the end of a war, Gorbachev consented to reunification and acknowledged the Cold War was over as the world moved in a vastly different direction.

Rather than dancing upon the grave of Communism, the United States engaged in careful, intentional diplomacy. It would have been tempting to replay the famous Nixon-Khrushchev kitchen debate, engage in triumphalism, and feed the narrative of American jingoistic swagger; but this was not the style of the Bush administration. When the Berlin Wall fell and Eastern Europe began to roll back the Iron Curtain, the Bush team worked behind the scenes to provide aid and comfort to the newly liberated countries, but care was always taken to avoid offending the Russians.

This polite diplomacy allowed the defeated communists to save face and find a new, less aggressive role on the world stage.

Russia had been a longstanding ally of Hussein’s Iraq, supplying it with weapon systems and financing the regime. One might expect that Russia would support Sadam and, perhaps, come to his defense, but Gorbachev chose first to broker a peace deal, which failed, and ultimately supported the conclusions of the UN resolutions. Perhaps most importantly, Russia stayed on the sidelines and did nothing to resist coalition forces.

This lack of action was unprecedented and signaled a complete change of tack by Russia. Unlike other Cold War hot spots, the Gulf War did not become a proxy war, but was a global effort; a real “united” United Nations coalition to act as a world police force to enforce the UN Charter militarily.

And it worked. Not only was there diplomatic consensus, but there was also military cohesion. The various and sundry coalition partners and their myriad of commitments and commands worked together, which resulted in Sadam being both isolated by the international community and overwhelmed by a lethal coalition force.

The Gulf War was over almost before it began. The sovereignty of Kuwait was restored, Sadam was humiliated, and it was reasonable to assume his international thuggery was over.

In fact, with the end of the Gulf War and the reunification of Germany, the world community seemed on the brink of a new paradigm in international relations. The United States was the only superpower left standing and reluctant as Americans were to take on a leadership role, the Bush administration was on the cusp of achieving what others had longed for: a stable and peaceful world with international cooperation and a global consensus on the role and implementation of the rule of law.

The world clearly seemed to be moving away from sentimental regionalism and toward a global economy with greater freedoms from governments that appeared to be democratically elected. The communism attributed to Marx and Lenin had died under the weight of a competitive international economy. Even China was developing a hybrid political and economic system that seemed to embrace some facets of capitalism while maintaining state control.

Regrettably, this brave new world that appeared truly transformed was only a mirage. Even though the United States was at the pinnacle of power, its leaders quit before solidifying their gains. As a peace-loving republic, America cashed in her peace dividend before maturity and took a holiday from history.

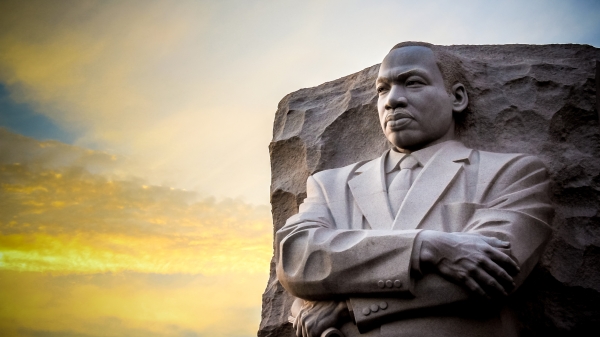

Too embarrassed to be assertive and advocate for our values, U.S. leadership chose to lead from behind. They assumed to our detriment that if our nation throttled back its role, others would join us. Rather than use our overwhelming might to force change on recalcitrant nations that questioned liberty and freedom, they choose consensus over taking charge—finding the lowest common denominator for action.

Even though past actions indicated otherwise, our leaders choose to bank on the good intentions of other countries with no history of personal freedom or democracy, much less the rule of law. Sadam was still in power, and like any good despot, he refused to accept defeat, consolidated what he had left, and continued to abuse his people with his power.

The U.S. foreign policy apparatus choose to look the other way when China reduced freedoms and clamped down on peaceful protests by killing demonstrators. Perhaps worse of all, Russia was allowed to drift away from true democratic reform and once again embrace autocratic rulers who used the trappings of democracy to gain power and whittle away at citizen self-rule.

Rather than continuing to advocate for American values on the international stage, our leaders, were content to be part of a timid chorus rather than standing as a loud voice for reason, practical diplomacy and strength.

The world is safer when America is fully engaged. The international community needs a strong America to provide leadership and, when necessary, to use the overwhelming might of its military. Our foreign policy aims must be clear and focused on self-interest and the significant implications of trade to expand our economy. With enlightened self-interest, America can provide global leadership and peace to the world. The United States can help create a stable world by advocating for a global framework that allows individuals within nation-states to pursue their respective political economies, peacefully and under rules of enforceable equity.