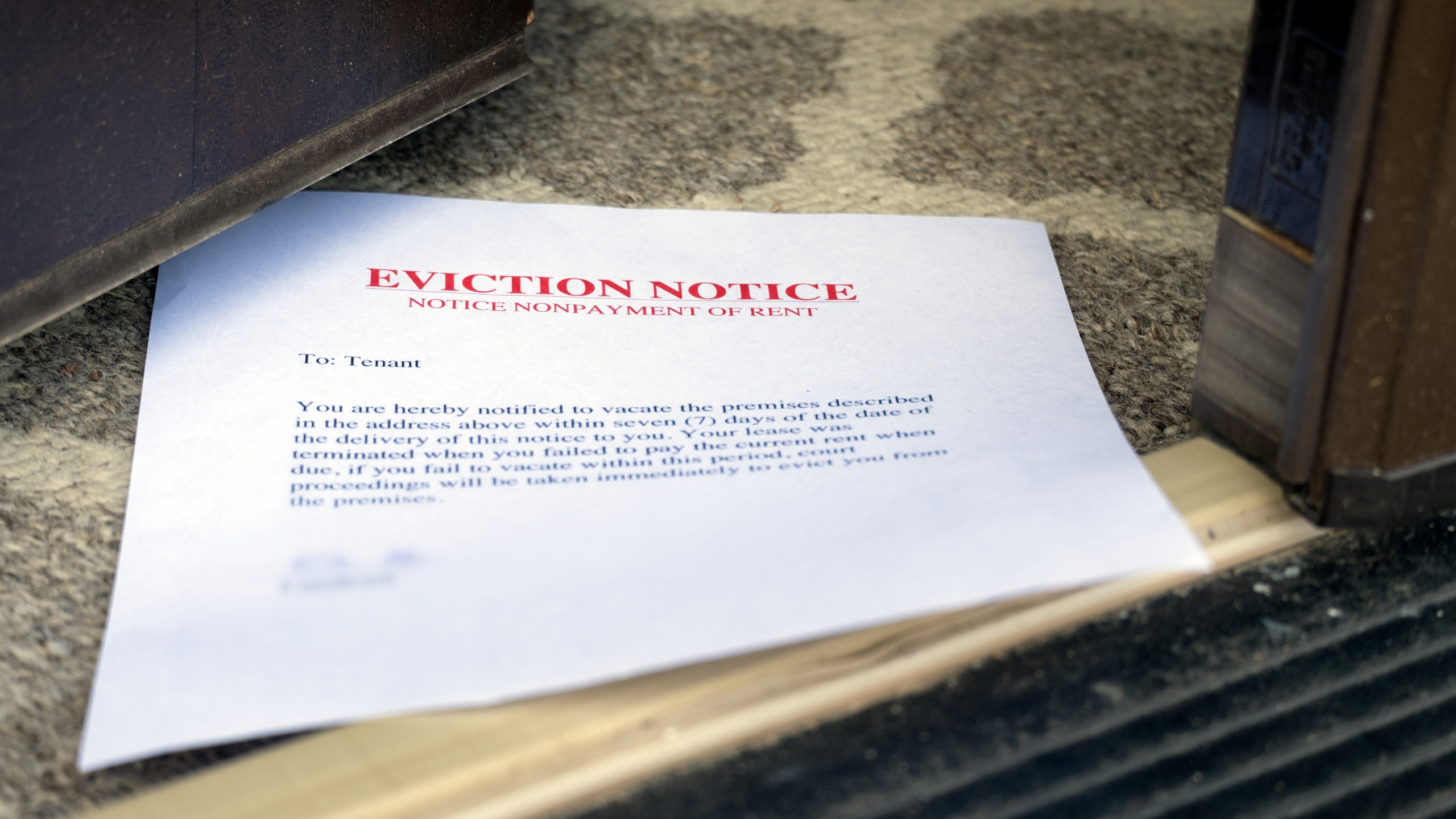

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a drastic impact on residential evictions in Alabama. The virus’s economic impacts have left families devastated, with some facing eviction for the first time in their lives, while a scattershot collection of local, state and federal moratoriums and restrictions have made the process difficult for the average tenant, and landlord, to navigate.

President Joe Biden has directed the CDC to extend its federal eviction moratorium, which was set to expire on Jan. 31, through at least March 31, 2021.

“As a protective public health measure, I will extend the current order temporarily halting residential evictions until at least March 31, 2021,” said CDC Director Rochelle P. Walensky. “The COVID-19 pandemic has presented a historic threat to our nation’s health. It has also triggered a housing affordability crisis that disproportionately affects some communities. Despite extensive mitigation efforts, COVID-19 continues to spread in America at a concerning pace. We must act to get cases down and keep people in their homes and out of congregate settings — like shelters — where COVID-19 can take an even stronger foothold.”

Dev Wakeley, a policy analyst for Alabama Arise, which advocates for policies that will help low-income individuals, said he doesn’t believe what protections are currently in place are enough for low-income tenants and others who face the prospect of eviction.

“During this time frame, what we would like to see is a categorical ban on evictions for anything, except for public safety reasons,” he said. “While this pandemic has had unfortunate effects on certain groups of people, everyone should have protection. And the CDC moratorium helps a lot of people but not everybody.”

Some evictions have continued despite the CDC’s protections, and one expert — Diane Yentel, president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition — told NPR that the federal moratorium was insufficient because it allowed some landlords to evict despite the protections. She also noted that no federal agency is enforcing the CDC’s moratorium protections if landlords do violate its requirements.

The moratorium is not an automatic ban on evictions. Tenants who may be covered by the moratorium — based on their income and losses due to COVID-19, and the threat of homelessness — must know how to seek protection by filling out bureaucratic forms. Already, research has attributed thousands of deaths to evictions as displaced and homeless families have been forced into more crowded shelters and other congregate living conditions.

A confusing legal process

Because of the dramatic economic pressure prompted by COVID-19, Gov. Kay Ivey issued a temporary halt on eviction proceedings in the state. That order expired on June 1, 2020. When the federal government’s initial moratorium on residential evictions was first issued in September, judges, landlords, law officers and tenants in Alabama and across the country were facing uncertainty with the eviction process.

As the state’s stay-at-home order came and went, and businesses and the state government began resuming more normal operations by May and June, some evictions ramped back up. By May 15, it was up to officials and judges in each county to determine whether to allow in-person hearings to resume, according to Rae Bolton, the lead attorney for Legal Services of Alabama.

“A lot began to start again but some continued to have hearings only by Zoom, including evictions,” Bolton said.

The CARES Act barred the filing of certain evictions from March through late July, with the CDC moratorium taking its place in early September, but the CDC moratorium — which Biden has extended through March — doesn’t block any case from being filed. Most renters in Alabama who meet the income and income loss requirements could be covered by the moratorium, but, in order to be covered, the tenant must fill out a form and provide it to their landlord.

“A tenant/defendant has to basically ‘opt-in’ to the protections by submitting the declaration form, and even then, courts are allowing lawsuits to be filed and placed on hold,” Bolton said.

Meanwhile, the moratoriums also slowed the court process for many cases as some courts struggled to keep up with new eviction cases and deal with the cases that were already backlogged in the court system.

“Where we have seen the biggest issue is that we are a few months behind on instituting evictions. Much of the court system was shut down for a great deal of the summer due to COVID-19, so this delayed any cases that were already in the system,” said Jefferson County Sheriff’s Sgt. Joni Money. “So, we are facing a backlog on those that were ordered by the court, but we couldn’t serve those along with the case backlogged in the courts.”

The CDC’s enacted regulations allowed tenants to potentially “stay,” or stop, an eviction case filed against them. While these rules and laws are helpful to tenants and the public’s health, proponents say, these stays have had consequences for the livelihoods of many landlords who rely on rental income to pay their own mortgages and other bills. Tenants covered by the CDC order do not have to pay rent until the order expires, meaning that landlords cannot receive rental income from those tenants.

“For these landlords, for some of them, it’s their business, and the government has sort of gotten in the way, where they might owe a mortgage on the property. And they don’t have the money coming in to pay it, so they have to use their own money to pay for it,” eviction attorney Brian Cloud said.

But once the order expires, some evicted tenants might have nowhere to go. Tenants will still owe back rent and late fees once they are no longer covered by the moratorium’s protections. Once the federal moratorium expires, the landlord can evict tenants and seek all the rent and late fees they owe through the court process. In the latest round of COVID-19 relief, federal funding was supplied to prevent evictions by paying landlords for back rent and fees if the landlords do not evict their tenants. But the legislation only provided $25 billion, and that total is not expected to be enough to solve the problem.

“If the moratorium is not extended or there’s not a comprehensive moratorium put into place, you’re going to see people being evicted … during a pandemic, who have absolutely nowhere to go,” Wakeley said.

Even with protections in place, the problem with the eviction process, at least for landlords, has been the slowness of the courts.

“The Jefferson County Courthouse has been very slow in acting. The courthouse actions that have occurred, the ones that we did need, have been very slow,” said Jack Eyer, chairman of the Birmingham-based Real Estate Investors Association.

Jefferson County District Court Judge Martha Cook explained why it took longer to process eviction cases.

“An additional factor affecting housing and the processing of eviction cases in Jefferson County is the closure of the Jefferson County Courthouse to the public from March 16, 2020, to May 1, 2020,” Cook said. “This closure, which I believe was completely warranted, prevented (those without legal counsel), who do not have access to our court’s electronic filing system, from physically coming into the courthouse to file an eviction case or, if a tenant, to file an answer or other response to the lawsuit. Also, the courthouse closure and the continued spread of COVID throughout our country and state have prevented the setting and hearing of trials at the same pace as pre-pandemic dockets.”

“Due to closure of the courthouse, Governor Ivey’s Safer at Home Order, orders and guidelines from the Alabama Supreme Court and our presiding judges, I did not set any in-person hearings or trials from March 16, 2020, until late August 2020. I heard cases via Zoom during this time, but not at the same volume I set in-person cases before the pandemic,” Cook said.

What comes next

Now that the federal eviction moratorium has been extended, judges and law officers will proceed as they have under the previous months covered by the moratorium.

“ I will continue to handle cases as I did under the previous CDC order,” Cook said. “In other words, if the tenant executes a CDC Declaration, returns it to the landlord or the Court, and the landlord does not successfully challenge the declaration or show why the eviction is not subject to the CDC Order, I will stay the eviction until … [the] date set by law.”

Wakeley said he’s still concerned that the extended moratorium, which ends on March 31, is not enough to meet the needs of people facing a crisis because of COVID-19.

“The eviction order extension will have an impact on the people who would have been evicted this month, but that financial need and those people behind on their rent payments are still going to be there,” Wakeley said. “While the aid package that is under discussion is better than what’s already gone out, it is not sufficient to address the real need that the American people have. Overall, we are going to need to see significantly more direct aid to people to stave off evictions.”

In order to help those who are behind on their rent, Biden plans to ask lawmakers for $30 billion in rental assistance and to also extend the moratorium to Sept. 30, 2021.