While thousands of National Guard troops and police officers patrol the nation’s capital on Inauguration Day, activists are concerned that Alabama’s gun regulations make it easy for violent extremists to make good on the kinds of threats that have the country on edge.

Dana Ellis, 67, of Hoover, a volunteer leader of the Alabama chapter of Moms Demand Action, said she’s worried that the state is vulnerable to threats like the plot against the governor of Michigan and to the deadly shootings of protesters in Kenosha, Wisconsin.

“We’ve not had that happen yet here, but the potential is here for that because our laws are so lax,” she said.

Of particular concern to her is that Alabama does not require background checks for buyers of firearms sold at gun shows and in private sales. Combined with the state’s open-carry laws and a national political atmosphere that increasingly features confrontations between opposing groups of demonstrators, this leaves plenty of room for people with criminal records or affiliations with extremist groups to show up to tense public encounters armed with high-powered weapons, she said.

Ellis’s group works advocates for “reasonable gun laws to promote a culture of gun safety,” she said, and is not anti-gun. Its membership includes many gun owners, in fact. But as a registered nurse for 38 years and a veteran of the U.S. Army Nurse Corps, she knows intimately what guns can do to the human body.

She’s also a survivor of gun violence, having been hit by shotgun pellets when she was 8 after an angry 14-year-old neighbor grabbed his parents’ unsecured gun and fired at her and her brother. She has lost two relatives to gun violence, one to suicide and one to homicide.

These experiences helped compel her to join Moms Demand Action, which started on Facebook after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School. Now, Ellis is alarmed at the zealousness of what she described as a loud minority of gun owners who believe that their freedom, and specifically their guns, are under threat of being taken away.

“It’s like a rallying cry. Of course, it hasn’t happened, has it?” she said.

It is this sort of grievance and the mindset that it contributes to that has prompted some historians, security officials and other experts to raise concerns about the U.S. moving toward a violent domestic insurgency.

Such conflicts have four main phases, according to the CIA Guide to Analysis of Insurgencies and the Department of Defense’s Joint Publication on Counterinsurgency. There is a pre-conflict phase, an incipient phase, an open conflict phase and a resolution phase, though not necessarily in that order.

Pre-existing conditions can increase the likelihood that a political situation devolves into an insurgency, which the CIA defines as “a protracted political-military struggle directed toward subverting or displacing the legitimacy of a constituted government or occupying power and completely or partially controlling the resources of a territory through the use of irregular military forces and illegal political organizations.”

Certain conditions may be recognizable to many Americans: lingering grievances against the government; societal factors like a strong warrior or conspiratorial culture; a polarized political system; inept or corrupt security forces; a “window of vulnerability” triggered by an event like a disputed election.

“During the pre-insurgency stage, insurgents identify and publicize a grievance around which they can rally supporters,” the CIA guide states. “Insurgents seek to create a compelling narrative — the story a party to an armed struggle uses to justify its actions in order to attain legitimacy and favor among relevant populations.”

The Southern Poverty Law Center issued a warning last month that false claims of fraud in the 2020 presidential election could become a “key belief of far-right radical groups — including those willing to use violence to achieve their political goals — into the indefinite future.”

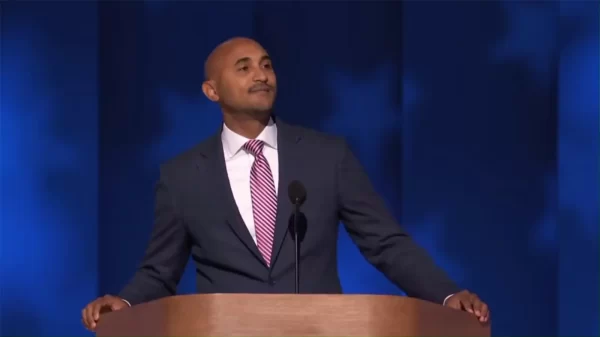

Whether violence escalates or not, Makayla Jordan, 17, of Birmingham, a volunteer with Students Demand Action, thinks that extremists are already taking advantage of relaxed gun laws in service of political ideologies. The specific grievance seems less significant than the raw power that guns represent, and she said she sees that dynamic play out largely along racial lines.

“White people wield these weapons just to make sure that whoever their opponent is — whether it’s Black and Brown people, people that they claim are trying to take away their guns, whoever — just so they feel powerful,” she said.

Jordan said that weapons are often characterized as tools of self-defense when brandished by members of groups like the Proud Boys but characterized as evidence of criminal intent when possessed by non-white people opposed to far-right groups.

Ellis said that her chapter, which has about 5,000 members on its mailing list, has repeatedly and successfully opposed proposed legislation to end the requirement for a permit to carry a concealed weapon.

She wants proactive legislation, however, to require background checks for all gun sales and to repeal the state’s open carry law. Ellis believes the measures can make the state safer from gun violence and safer for responsible gun owners.

“I think the majority of Alabamians feel this way,” she said.