There were no intensive care beds available in Mobile County on Tuesday, the second day in a row Alabama set a record for hospitalized COVID-19 patients, and if models hold up, there could soon be the need to set up temporary medical facilities outside of hospitals, according to a UAB infectious disease expert.

Dr. Jeanna Marrazzo, director of UAB’s Division of Infectious Diseases, told reporters on Tuesday that looking at some models that forecast what might happen in the three weeks after Thanksgiving “you could conceivably see a true need for setting up ancillary care places in three weeks.”

“I hope that doesn’t happen. Are we looking at the kind of situation that New York City experienced in March? A lot depends on what happened over Thanksgiving weekend,” Marrazzo said, referring to the use of tent hospitals in New York City during the early spring surge there that overran hospitals.

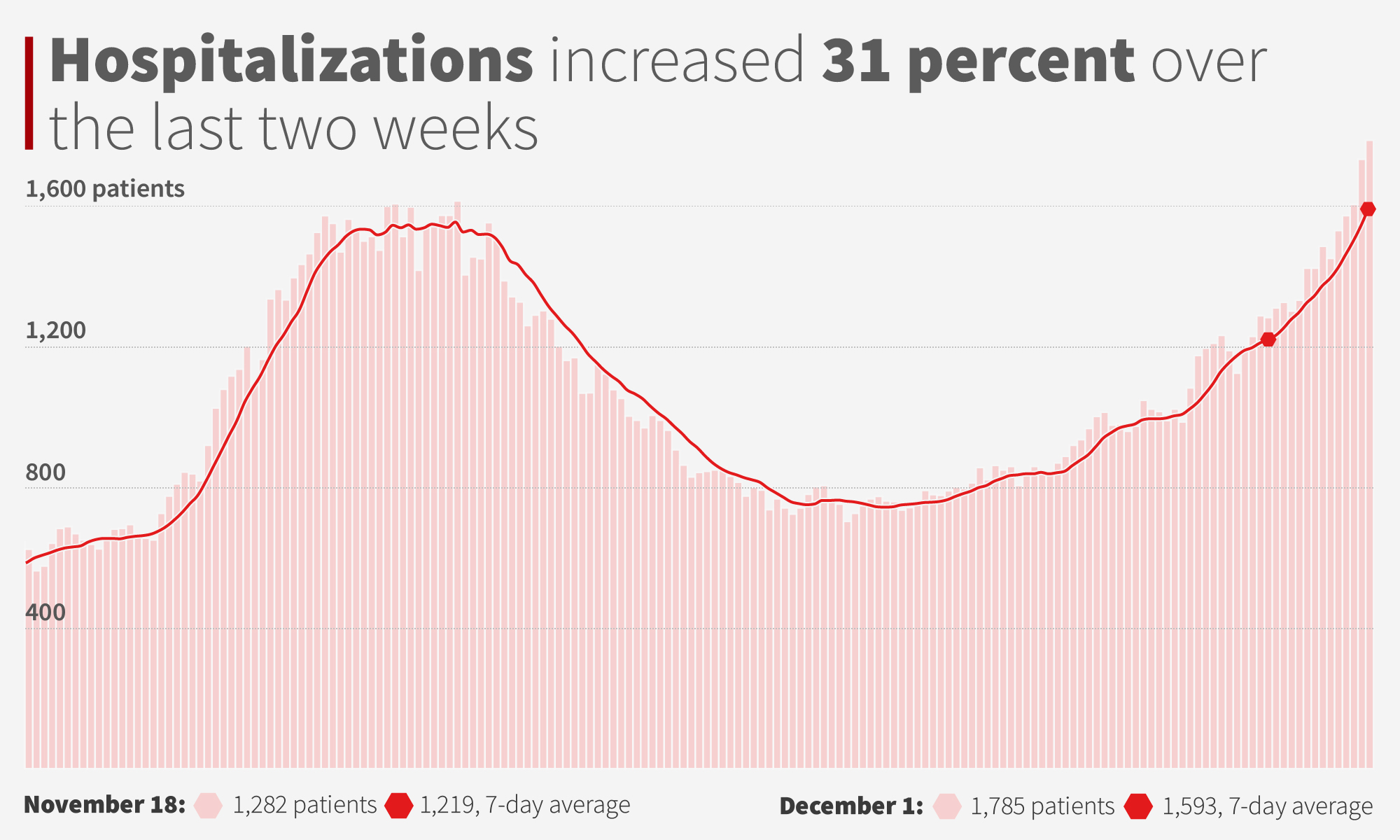

UAB had a record high 125 COVID-19 patients hospitalized on Monday and Tuesday, and Huntsville Hospital also set a new record Tuesday, with 317 hospitalized. There was a record high 1,785 COVID-19 hospitalizations statewide on Tuesday, and on Monday there had never been fewer intensive care beds available in the state.

Marrazzo said the health care workforce continues to work valiantly and are “struggling very hard.” What keeps her up at night, she said, is worrying if hospitals will have enough staff to handle “what might be a tidal wave of patients in the next month.”

“It may not look like we can affect what’s going to happen in two to three weeks, post-Thanksgiving, but we can impact what happens around Christmas time and after that,” Marrazzo said.

{{CODE1}}

The death toll from COVID-19 continues to increase across most of the country, Marrazzo said. On average, the U.S. is seeing between 1,400 and 1,600 people lose their lives to coronavirus each day, she said. In Alabama, at least 3,638 people have died from COVID-19.

Alabama reported an additional 60 deaths on Tuesday and has averaged at least 24 deaths reported each day over the last two weeks.

Each morning, Marrazzo gets a list of those admitted to UAB for COVID-19, those discharged and those coronavirus patients who have died. Not a day goes by when there isn’t one name on that list of someone who didn’t make it, she said.

“And I think about that person, and I think about their family,” Marrazzo said. “And unfortunately those numbers, as I mentioned before, are going up, and the balance of people being admitted is higher than the number of people who are being discharged.”

{{CODE2}}

Alabama added 3,376 cases on Tuesday, which was the largest single-day case increase, excluding when on Oct. 23 ADPH added older backlogged test results. Tuesday’s high number was the product of a delay in reporting to ADPH due to the holiday weekend, the department said in a data note.

Still, Alabama’s case count continues to increase alarmingly and testing is still down, Marrazzo explained. The state’s 14-day average of new daily cases on Tuesday was at 2,289. That’s a 28 percent increase from just two weeks ago.

“This is a really, really scary inflection point, “Marrazzo said, “and I don’t think that we are going to be able to turn it around without experiencing some more stress and some more pain.”

{{CODE3}}

The positivity rate in Alabama over the last week has been an average of 32 percent, more than five times as high as public health experts say it should be to ensure there are enough tests and cases aren’t going undetected.

“If we would test more we would probably find more, so I think these numbers are an underestimate,” Marrazzo said.

{{CODE4}}

Asked what has gone wrong, that even with the knowledge of how people can protect themselves — wearing masks, practicing social distancing and staying home as much as possible — we’re still seeing huge spikes, Marrazzo described a complicated set of circumstances.

“Is it because they don’t believe it’s going to affect them?” she asked.

At first, COVID-19 was something happening in China, and then it moved closer to home, Marrazzo explained. Next, it became a question of “well, it’s older people who are getting sick,” and there was a sense of invulnerability among the young, who thought they’d be fine and that they wouldn’t infect others, she said.

“And then I think even for people who have been trying to be good there’s a huge amount of fatigue,” Marrazzo said. Even health care workers become worn down, and may take risks they know they shouldn’t and become infected in their own communities, she said.

“I think we’ve been hammering it home, but I also think in some ways, we need to do it in a way that’s sympathetic and not angry,” she said. “Because yeah, I’m pretty upset about what’s going to happen in the next couple of weeks, but getting angry with people and shaming them is not the answer at this point, so I think all we can do is to continue to report on the facts.”