By the time State Rep. Alvin Holmes reached someone in the office of Gov. Jim Folsom Jr., it was far too late. Or, at least, that’s what they thought in Folsom’s office.

Mercedes Benz was on the way to Tuscaloosa County. The deal had closed, the site work was underway, and to sweeten the pot from the state’s end, Folsom had sent the Alabama National Guard to Vance to help with site prep.

That was a serious misuse of the Guard, in the eyes of Holmes (and of many others). The Guardsmen aren’t pawns for business deals. So, Holmes, who already had raised hell about the behavior of state lawmakers and Mercedes officials, called Folsom’s office to tell them it wasn’t right and to put a stop to it.

They laughed at him and hung up.

Bad move.

“The next thing Alvin does is call up Ron Brown, who was the Secretary of Commerce at the time,” said former state Sen. Dick Brewbaker, who also served with Holmes in the House. “He tells Ron he wants to speak to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs.”

Holmes didn’t get quite that far to the top, but he got high enough. Before the night was over, a phone call was placed from a 3-star general to the head of Guard in Alabama.

“Word came down that there shouldn’t be a single man or a single piece of equipment at that site at daybreak,” Brewbaker said, chuckling.

Holmes called the governor’s back.

“They weren’t laughing then,” Holmes told Brewbaker.

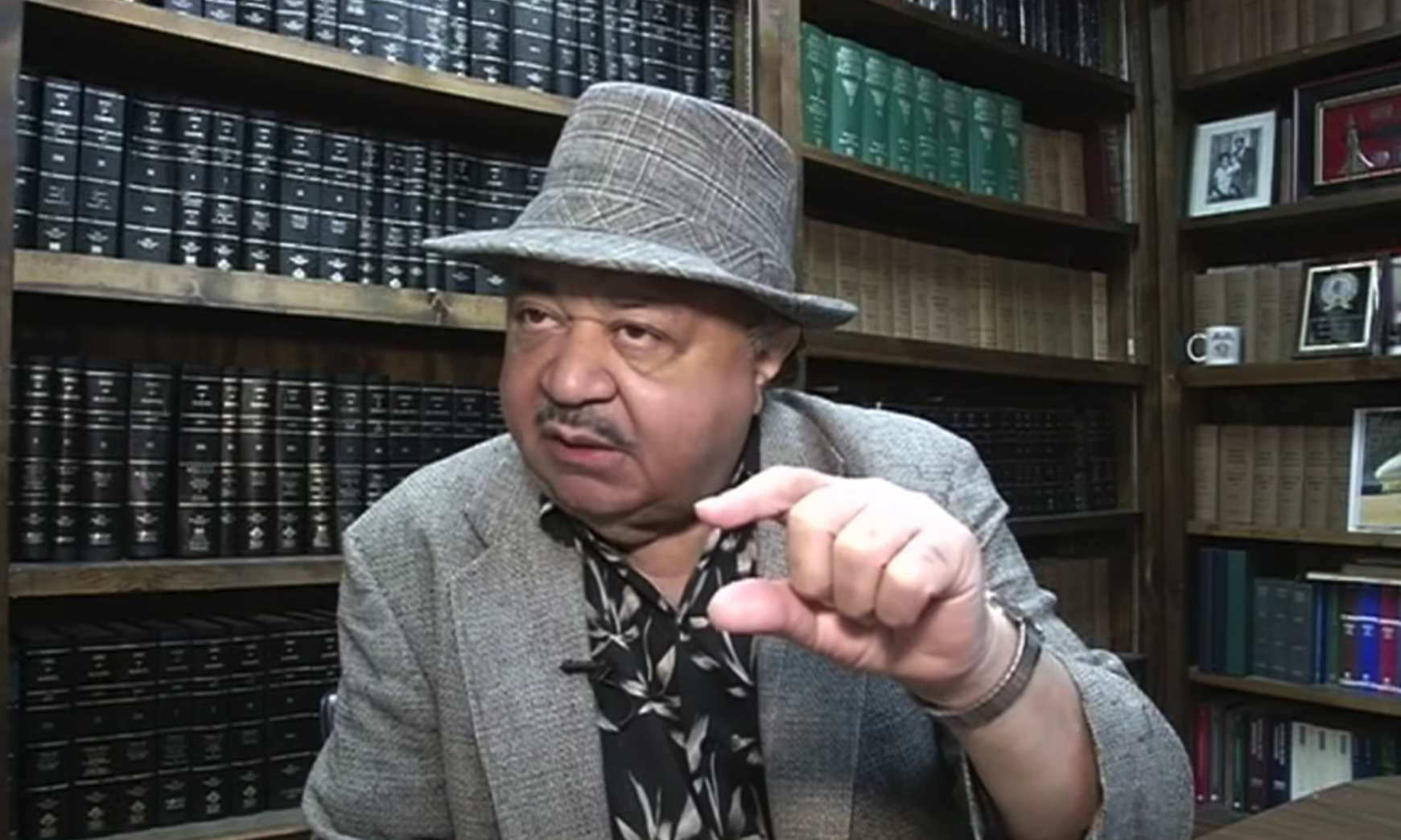

That, in a nutshell, was Alvin Holmes: a master of the rules, a pain in the backside to anyone he thought had strayed, a relentless debater, a tireless advocate for the Black community and the most purposefully underestimated man in the history of Alabama politics.

Holmes passed away Saturday, at the age of 82. But during his 44 years in the Alabama House, he provided endless stories of his epic rants on the State House floor, bemoaning the treatment of Black citizens or the working poor or even that dastardly foreign beer from Germany.

He often said outlandish things and made biting, personal attacks on his fellow members — most of it aimed at drawing attention to the larger point he wanted to make. But those moments at the mic also had another effect, serving to paint Holmes, especially in the minds of white people, as a blustering, ranting imbecile.

And that’s exactly what Holmes wanted.

“I’ve never met another politician in this state who wanted to be underestimated — who worked to make people think he wasn’t as smart as he was,” Brewbaker said. “Alvin loved it. He wanted people, especially those in the Legislature, to underestimate him. And then he’d tie them in knots.”

Holmes underplayed his intelligence better than anyone I’ve ever known, baiting his foes and luring them into the trap over and over again. To watch him work his marks on the House floor was like watching Greg Maddux pitch.

“Help me understand,” Holmes would start, as he questioned a bill’s sponsor about some specific language buried deep in a lengthy piece of legislation, and in a matter of seconds, the backtracking and stammering would begin.

When he sensed fear or uncertainty, Holmes was merciless.

“It’s not my job to be nice,” Holmes told me once. “It’s my job to make sure the people know the racism and disenfranchisement many of my white colleagues want to codify into law.”

And Holmes was very, very good at his job.

Over the course of his 44 years in office, it’s fairly safe to say that Holmes called out more racists and challenged more discriminatory laws than anyone. And the way he did it — so boldly, so unapologetically — was, especially in the 1970s, a shock to an Alabama system that had only recently emerged from Jim Crow.

In 1975, his second year in office, Holmes tricked lawmakers into approving a bill on a voice vote that required the state to hire more Black people. When the white lawmakers complained, Holmes brushed them off and said, “I think they’ll pay more attention next time. If they want to sleep, let them sleep.”

In the early 1990s, during a fight over the Confederate flag flying above the state capitol — a fight that would make Holmes one of the most hated men in the state — Holmes pulled no punches. He called then-Gov. Guy Hunt “one of the most notorious racists who ever served the state.” And then he added: “Not only a racist but a stupid racist.”

In his later years, Holmes could still bewilder his Republican counterparts and his rants — while fewer and often more humorous than biting — were still newsmakers, but Holmes had clearly grown tired.

By the time he was defeated by Kirk Hatcher in 2018, Holmes barely put up a fight and agreed it was time to move on.

Who could blame him if he was a bit tired? For more than four decades, Alvin Holmes withstood a barrage of hatred and anger that most can’t imagine. For years, he was the solitary focus of many white supremacists and the mascot that conservatives in the Alabama Legislature used to push through hateful, racist bills.

While Holmes always seemed to court such hostility — to invite it and embrace it, at times — such a life was undoubtedly lonely and exhausting.

Here’s hoping that wherever Alvin Holmes is today, the beer drinks plenty good, the injustices are solved and there’s finally time to rest.