Alabama’s seven-day average for new daily COVID-19 cases on Wednesday was as high as it’s ever been, and an infectious disease expert at UAB described the state’s high positivity rate as a sign of “borderline out-of-control community transmission.”

Dr. Jeanne Marrazzo, director of infectious disease at UAB, told reporters during a briefing hosted by Sen. Doug Jones, D-Alabama, on Wednesday that the state is seeing the consequences of uncontrolled transmission in rising cases, hospitalizations and deaths.

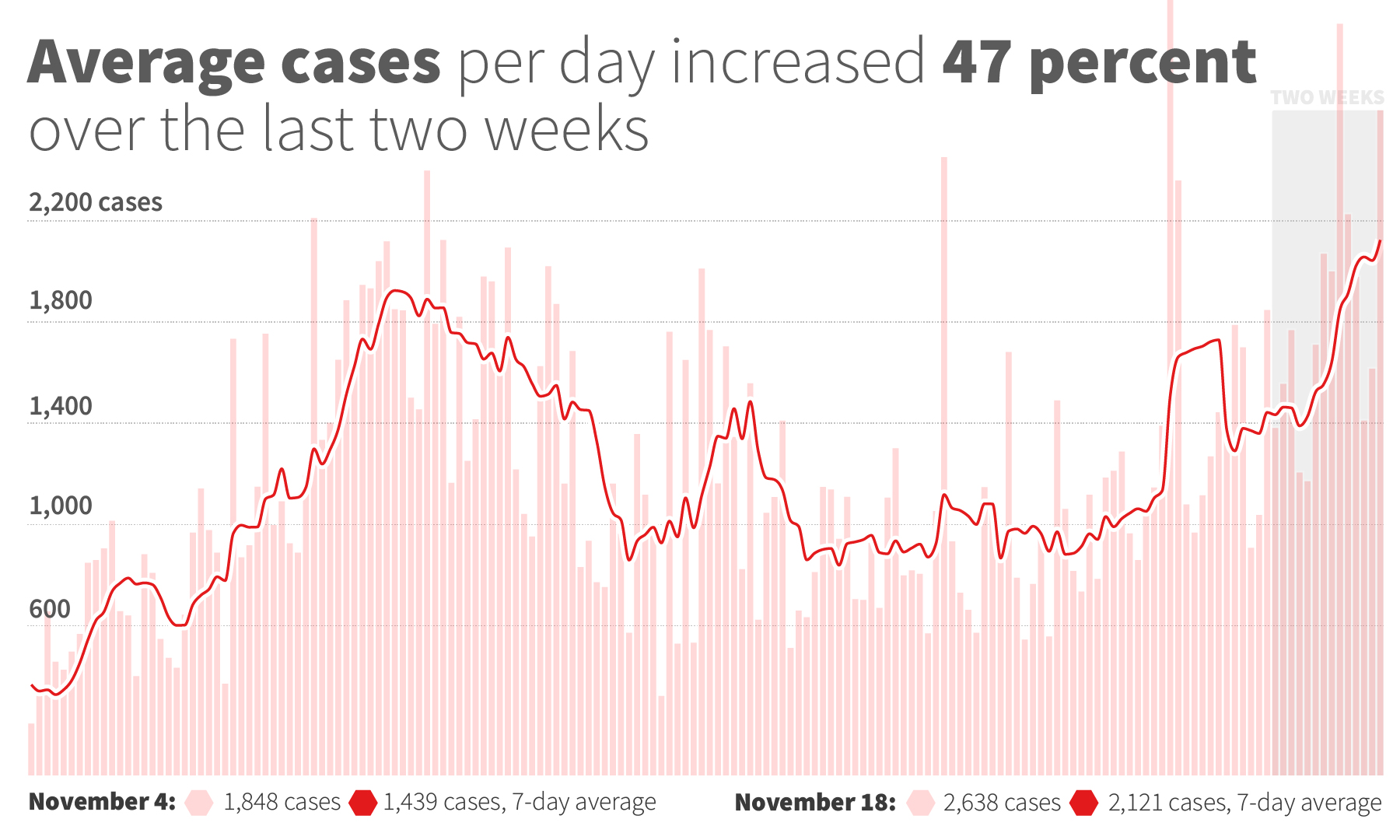

Alabama on Wednesday added 2,638 cases, bringing the seven-day average of daily cases to a new record high of 2,121 cases. Wednesday’s record-high number was the third such record in the last four days. Public health experts say the high level of community spread is a sign of a potentially deadly holiday season if families gather together as if things were back to normal.

{{CODE1}}

Alabama’s 14-day average positivity rate was 23 percent Wednesday, according to APR’s calculations — nearly five times the ideal threshold public health experts say is needed lest cases are going undetected.

{{CODE2}}

Asked about Alabama’s high positivity rate, Marrazzo noted that the percentage began dropping in late spring in some areas in the state, which was a good sign, but that the numbers didn’t remain low.

Testing is down statewide, she said, and some days the Alabama Department of Public Health includes backlogged test results in the daily data, which can skew the numbers, but the upward trend is still troubling.

“I think our numbers are high because we are simply continuing to experience really borderline out-of-control community transmission,” Marrazzo said, adding that she’s concerned as we approach Thanksgiving that the spread might worsen if people don’t take precautions.

“Most of the transmission of this virus is coming from people who either haven’t yet gotten their symptoms or are never going to develop symptoms,” Marrazzo said, referring to pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals who can still spread the virus.

Marrazzo said Thanksgiving presents a particular risk because of the mixing among different households. “That’s when things start to fall apart,” Marrazzo said.

Marrazzo discouraged people from treating COVID-19 test as an all-clear. Just because someone receives a negative test before heading home for the holidays does not mean they have no already been exposed and infected. A person can become infected yet not test positive for two days afterward, she said.

The better approach, Marrazzo said, is to make certain you’re not infected “and then essentially keep yourself in some sort of bubble for about two weeks.”

“And then go home to your family, or to who you know. People that you think are also going to be relatively safe,” Marrazzo said.

Alabama hospitals on Wednesday were caring for 1,303 COVID-19 patients, a number not seen since Aug. 14. The state’s seven-day average of daily hospitalizations was at 1,222 — a 45 percent increase from a month ago.

Marrazzo said hospitals are already discussing the possibility of barring some elective procedures due to the rising COVID-19 hospitalizations.

“We really don’t want this to happen,” Marrazzo said. “But it’s inevitable that we are going to be faced with this if the trajectory of hospitalizations continues to climb.”

{{CODE3}}

The Alabama Department of Public Health (ADPH) on Wednesday reported 46 new COVID-19 deaths, and 56 on Tuesday. Over the last 14 days, 341 deaths have been reported, the largest 14-day total since Aug. 12, when the state’s death toll was at its highest in the weeks following Alabama’s summer peak.

Deaths are lagging indicators of the spread of coronavirus and can take weeks and even months to occur after infection, and it takes the Alabama Department of Public health time to collect and analyze data to confirm a COVID-19 death.

{{CODE4}}

While large numbers of deaths were reported by ADPH on Tuesday and Wednesday, the date those people died stretches back to March, although at least 30 of those occurred since Nov. 3.

Data for the last two weeks is incomplete and is likely to rise.