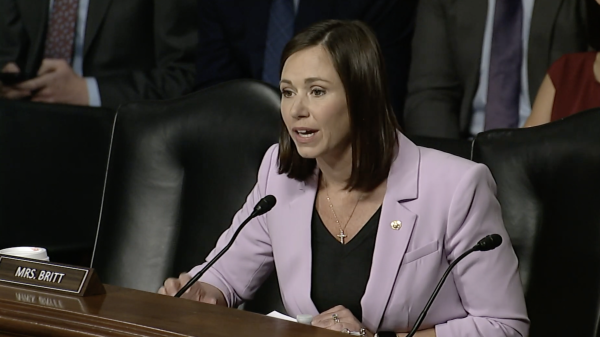

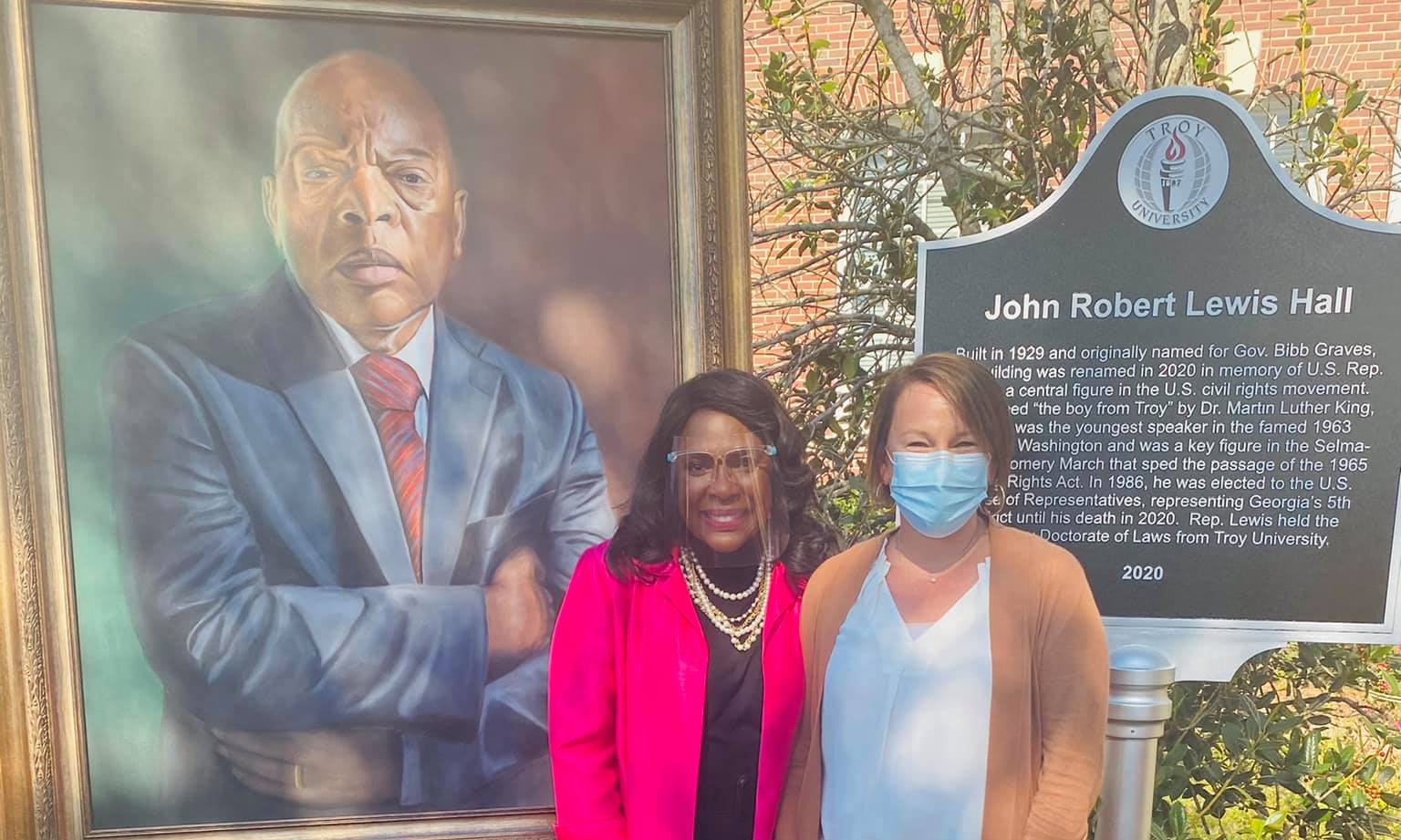

Troy University last week dedicated a hall to Troy native the late Congressman John Robert Lewis. Speakers at the event included U.S. Reps. Martha Roby, R-Alabama, and Terri Sewell, D-Alabama. Also speaking were Lewis’s nephews.

Roby said: “Last week, I had the honor to attend the dedication of John Robert Lewis Hall at Troy University. Not only was it a significant occasion for the people of Troy University and the Troy community, but it was also a very special moment for the entire state of Alabama. His legacy will be remembered by all for years to come.”

Sewell said: “Honored to be at Troy University for the naming of the John Robert Lewis Hall! What a befitting honor for John, my dear friend and mentor. Gone but never forgotten! Rest in Power!”

Lewis’s nephew talked about the importance of “good trouble.”

Hundreds gathered in the legendary civil rights icon’s home county to celebrate the naming of an academic building in his honor. Lewis was born to a family of sharecroppers near Troy. He was denied attendance at the university in 1957 because of segregation.

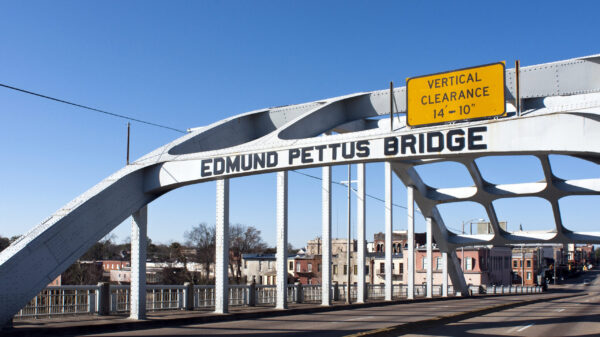

He spent decades fighting segregation, most famously at the Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights march, where he was beaten by state troopers, local law enforcement and others.

“To see this happen in his hometown of Troy, in a city where he was once denied his basic right to education, he would have been overcome with pride and gratefulness,” said Jerrick Lewis. “My uncle would have been proud to have his name displayed on this building, and he would’ve been proud of this university for showing the world what it truly stands for: unity and equality over hatred.”

Troy University’s Board of Trustees voted unanimously in August to rename Bibb Graves Hall after the congressman, who died in July at age 80.

“It is the right thing to do to name this building for a great man,” said Troy Chancellor Dr. Jack Hawkins Jr. “I am proud of our Board for making that decision. On July 25, we honored John Lewis for a day. Today, we honor him for an eternity.”

The university had honored Lewis with a memorial service on July 25, but the rededication marked a chance for the university to cement his legacy with a building on campus.

Troy University honored Lewis with an honorary doctorate during his lifetime. Lewis was the youngest speaker at the Civil Rights rally in Washington, and when he passed away earlier this year he was the last speaker at that event to die.

“On behalf of the family, I’d like to thank Dr. Hawkins and Troy University for being the perfect example of change and progress,” said Ron Lewis, another of Lewis’ nephews.

“He was known as the conscience of Congress,” Roby said. “He was a true American patriot. We had the great privilege of serving with John.”

“No one represents the resilient spirit of the state of Alabama, the city of Troy and Troy University like the ‘Boy from Troy’,” Sewell said.

Trustee Lamar P. Higgins said the building represents a man who paved the way for others.

“If it weren’t for John Lewis, Lamar Higgins wouldn’t be here today,” Higgins said. “If it weren’t for John Lewis, a lot of great things about this country would not have happened. We’re grateful for all that he has done.”

Board of Trustees President Pro-Tem Gibson Vance said he hopes TROY students learn from Lewis’ example in the years and decades to come.

“We hope they’ll be inspired by this man to go out into the world and make it a better place,” Vance said.

Bibb Graves, for whom the building was previously named, played for the University of Alabama’s first football team, commanded the Alabama National Guard on the Mexican border in 1916 and served as a colonel in World War I. He organized the American Legion in Alabama and was the governor of Alabama during most of the Great Depression serving from 1927 to 1931 and again from 1935 to 1939.

But he was a Ku Klux Klan member, running for office in the 1920s at the height of the Klan’s popularity, but Graves was very liberal for the South at the time. He was a staunch opponent of eugenics sterilizations, a New Deal Democrat who supported Roosevelt’s efforts to grow the role of government, ended the state’s convict leasing system and condemned forced segregation in Birmingham. Graves spoke at the founding meeting of the Southern Conference on Human Rights, a conference of southern liberals attended by both white people and Black people during the height of segregation.