While the Huntsville City Council and local activists await a report by the Huntsville Police Citizens Advisory Council about police actions in June, two lists of potential reforms sit ready to be considered.

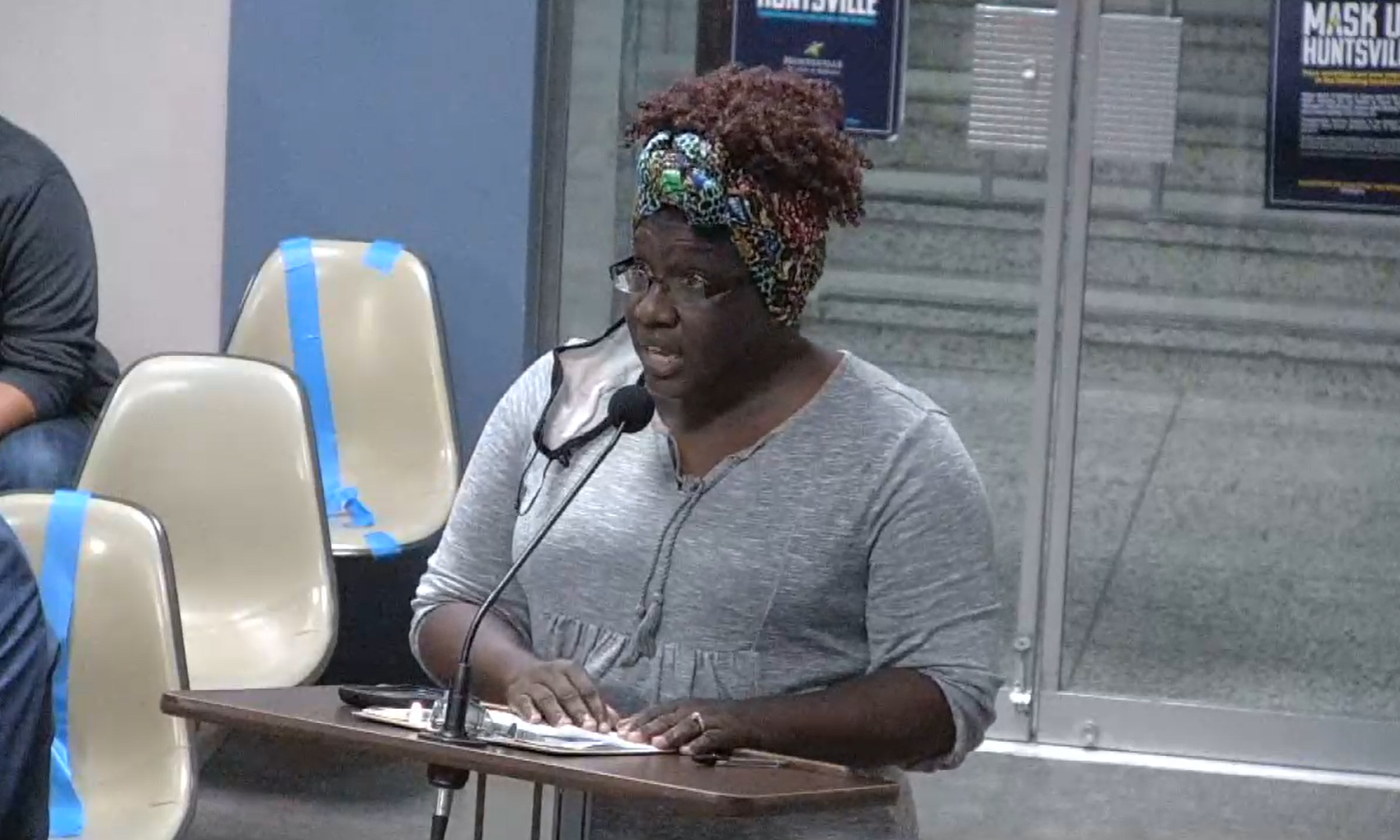

The lists were created by the Citizens Coalition for Criminal Justice Reform, the activist group established by Huntsville resident Angela Curry. The first is 10 specific requests that Curry compiled based on conversations with dozens of residents. The youngest was 16 and the oldest was 83, she said. She asked each person what they would change to make law enforcement better, and some common themes emerged.

The result was 10 of the simplest things the community could ask of its leaders and police, “that you would look at this list and say, hey, we don’t have these things already?” Curry said.

Activists have described city leaders as reluctant to engage with them in meaningful ways. Officials publicly pronounce a desire to improve police procedures and community-police relations but don’t address what might be wrong with current procedures, and CCCJR members say that only Councilmember Frances Akridge has been willing to meet with them.

Mayor Tommy Battle did not respond to a request for comment, but he mentioned the issue at a City Council meeting on Nov. 5, saying that his administration would meet with residents who have been in touch but only once the HPCAC completes its review. He wants the review to be conducted independently, he said.

“I have some strong feelings on that. I don’t want influence from council and I don’t want influence from the administration,” Battle said.

At the same meeting, multiple members of CCCJR used their allotted three minutes during public comments to describe specific reform measures that are not connected to police actions in June. Many expressed frustration at what they see as the council’s resistance to any acknowledgment that there are problems with Huntsville police policies, training or officers’ behavior.

CCCJR’s list is as follows, with explanations by Curry, lightly edited for clarity:

- All standard operating procedures (SOPs) and use of force policies will be made available to the public (online). Citizens and officers should be equally informed on these policies, which involve citizen and police contact.

Curry: We constantly hear, “If the citizen would have just followed the law or complied then they would have been ok and the situation wouldn’t have escalated.” So what are the laws and the policies? What are police procedures when someone has an encounter? If an officer is the only one on the scene who knows what should happen, why is there this expectation that a citizen is able to respond “accordingly” to policy? I talked to two young Black males who wanted to know why, when they get pulled over, they are always asked to get out of the car no matter what they were pulled over for. They wanted to know if that is policy. Others wanted to know if they have to give their names when asked, and if the officer is supposed to identify themselves. The officer can say whatever they want, and because we do not have the policy, we do not know how the interaction is supposed to go.

- Annual training on agency SOP and use of force policies for officers, as part of their required annual Alabama Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission (APOSTC) continuing education, will be required, with completion certificates publicly archived.

Curry: We assume they complete the training and pass their assessments but we don’t know that that’s the case. It’s just bringing more visibility to public employees. If you go to a restaurant, their health code score is publicly posted so you know if they’re following the guidelines set by the Health Department. So if officers are trained in use of force and a certain officer has 50 complaints related to use of force, well here’s the public acknowledgement that they were trained, so then what is causing these use of force complaints?

- Documented explanation of the hiring process for officers, with specific information provided about screening processes. Example: Mental health screening and background screening (even via social media) to determine any racial bias/discriminatory tendencies of a cadet.

Curry: How do we know they’re not hiring racist cops? Are they doing mental health screenings to see if they’re suffering from PTSD? Are they checking their social media accounts to see if they’re part of an alt-right group? Or do they just take their word for it? My mindset was, you know, we often accuse officers of all these horrible things without having established if there is evidence to the contrary. This should give some reassurance to the community that the department didn’t just hire Billy Joe Bob and his cousin because they needed a job – that they actually screened these individuals with the public in mind, for their ability to interact with the public professionally. This can establish more trust.

- Crime-mapping data from each law enforcement agency in Madison County will be provided to the public via each agency’s webpage.

Curry: If we can demonstrate a low crime rate, it would help to boost the economy because tourists could see which areas are the safest and feel good about staying in our city. There’s a stigma that north Huntsville is just crime-infested. Well, this crime-mapping data would prove or disprove that, or open a conversation about whether this area is being over-policed, causing much more crime to be recorded than in other areas of the city. These data points could be explored if they were publicly available, but they’re not.

- Provide officer complaint information from each agency in Madison County on their respective agency webpage, to include the nature of each complaint and disposition. This includes instructions for how a citizen can file a complaint, what is required and where to go to submit complaints.

Curry: I’ve listened to people say that they didn’t know where to go, the officer wouldn’t tell them, they’d have to go to Internal Affairs, you have to tell the person at the desk why you’re there, they ask you to give an account of your whole complaint, then they have you go to another room and they ask you the same question, they finally give you some paperwork and put you in what looks like an interrogation room, and they repeatedly come in and ask if you’re done yet. Then they give the complaint to the appropriate shift officer who just says that the officer in question followed policy. Well, who’s going to say that their officer didn’t follow policy? There should be an independent review. And we’re in the space and rocket city in 2020 — you should be able to file a complaint online. If I’ve had a bad encounter with an officer and I have to go explain it to a higher-ranking officer who has a sense of loyalty to their officer brother or sister, I don’t know how helpful they’re going to be in helping me file a complaint versus trying to discourage me from doing it. If you look at the department’s annual reports, it looks like we hardly get any complaints.

- Provide the public with details from each agency in Madison County as to their procedures for handling officers who are discovered to have exhibited racial bias or discriminatory tendencies.

Curry: People experience this sense of entitlement or power-tripping on the part of officers, but it only appears around people of color or people they think of as lower-class. They behave very arrogantly or are very condescending, people will say. One guy heard a cop say hello and call him sir, and the guy looked around because he thought the officer was talking to somebody else. He was 32 years old and it was the first time an officer had talked to him as a peer, as an equal. Others say they’ll see cop cars and know they’ll be pulled over without cause, and then they are. Things of that nature.

- Recommend a third party panel consisting of members of the community to review agency SOPs for evidence of bias and over-policing. Report those findings to the public.

Curry: The HPCAC is supposed to review policy and make recommendations, and they say that they’ve done that in their 10 years in existence, but they don’t report it publicly. So that part is specific to them because that is what they’re supposed to do. We didn’t know if they look into racial bias issues, so we wanted to make sure that if this is not something they’re doing, can they add it to their list. And then can you make it public? Why is it secret?

- Recommend a diverse Citizen Complaint Review Board composed of members of the African American, Hispanic, Asian and Caucasian communities to review citizen complaints, and allow this panel to make SOP-rooted disciplinary recommendations to the mayor, city council and agency executives.

Curry: This group would look at any and all civilian complaints that come in. Internal Affairs would also get them, but this group would examine them from a citizens’ perspective. The HPCAC seems to be a policy review board that examines something if they’re asked to. This new board would exist specifically for complaints. Citizens could file complaints directly to the board through their website, which would also go to Internal Affairs but wouldn’t be required to go through them. It creates additional oversight.

- Ensure a 100 percent transparent process for releasing law enforcement body camera footage to the public.

Curry: We don’t know what the process is, but from what I remember from HPD presentations given this summer, if you are a loved one or you were in the video, you make a request to see the body cam footage. HPD responds to your request and then arrangements are made for you to see it. But we know with Crystal Ragland, it took them at least six months and they limited the number of people who could go see the video footage. Their family has six immediate family members, but police told them that only three members could view it. When Crystal’s mom asked them how she was supposed to decide which members would go with her, they stopped talking to her.

- Respond to the Tennessee Valley Progressive Alliance’s communication regarding the decriminalization of marijuana.

Curry: Everybody misreads this one. The TVPA had done research on this issue to present to legislators and law enforcement. The group reached out to Huntsville officials but never got a response [beyond an acknowledgment that their letter was received]. The only thing we’re asking is that they respond to this group. The City Council members we’ve heard from take it as, “You want to decriminalize marijuana and that’s a state law.” We would like to do that eventually, but if a group comes to them and makes a request, they should at least give them the respect of replying. If they won’t even respond to an inquiry about it, they’re not ready to address it. It foreshadows the fact that we are a group making a request — we’ve done research, we didn’t just throw out some willy-nilly list — and then you don’t want to meet with us either. It establishes a pattern.

In October, Curry and CCCJR organizers consulted Ademali Sengal, a senior organizer with the Grassroots Law Project, a national group that advocates for policing and justice reform. Sengal had initially reached out to City Councilmember Frances Akridge to discuss how Huntsville was allocating its police budget. Akridge referred him to CCCJR and connected him with Curry.

Sengal asked what ultimate goals they wanted to see realized. Their responses formed the second list of six main components of a reform package, as follows:

- Behavioral health (rather than police) deal with non-police calls. Decriminalize mental health and homelessness.

- Broad access to law enforcement agency public information on the internet.

- Accountability for bad policing, to include prosecution, jail time and the loss of eligibility to work as a police officer anywhere (ensured by decertification and entrance into a centralized database).

- An HPCAC with teeth, and with a membership that is representative of the entire community.

- A regional public safety task force which provides oversight of law enforcement agencies in northern Alabama.

- A state law that governs all body camera footage for all law enforcement agencies in the state.