In the weeks after police and sheriff’s deputies fired rubber bullets and tear gas at peaceful protesters in Huntsville on June 3, people who had been at the protests or who supported them started showing up at city council meetings. They called for the police chief to be fired, for an investigation and for deep reforms, but at minimum, they wanted to see their outrage reflected by city leaders.

Instead, many say, they have been met by passive listeners who seem more concerned with maintaining decorum in the meetings than taking any decisive action. The council ordered a review by a board of appointed citizens, but it meets behind closed doors and has been tight-lipped about its fact-finding process and deliberations.

Small protests have continued, including outside the home of Mayor Tommy Battle. While the demonstrations sustain some level of noise, something else has grown more quietly: A coalition of more than 2,000 Madison County residents who aim to change local government if it is unresponsive to their concerns.

A grassroots effort

Angela Curry, 48, founded the Citizens Coalition for Criminal Justice Reform, a network of individuals and small specialized groups, in early June. She had noticed that many of the Huntsville residents protesting the killing of George Floyd did not know each other, she said. Many were demonstrating for the first time.

Curry started a Facebook group on June 2 to help people stay connected, hoping it would keep some of their energy going after the protests died down. Police fired on protesters the next day.

Nearly 2,000 people have joined the Facebook group. Of those, 244 are volunteers working on a five-year plan for criminal justice reform that can be implemented at all eight local law enforcement agencies in Madison County. Among them are attorneys, former law enforcement officers, educators and others whose career expertise adds to the holistic nature of the coalition’s approach.

That includes considering the well-being of officers, Curry said. The group is examining how they’re being represented in terms of benefits, mental and behavioral health and job expectations. Curry noted the high rate of suicide among police nationally. It was more than double the number of deaths in the line of duty in 2019, according to the organization Blue H.E.L.P.

Understanding the unique pressures of police work and their effects on officers, and how leaders handle those effects, is key to the conversation that CCCRJ is trying to start, Curry said. There shouldn’t be a wall between police and citizens, she said — officers are part of the community.

“Fear is the common ground that officers and citizens are currently functioning from, and if we can replace that with empathy and humanization then we’ll have a community police force because there’ll be mutual respect,” she said.

Also key is an understanding of what systemic racism is, Curry said. It isn’t the personal beliefs of individual people. It is how rules were written historically to prevent Black people from achieving the wealth, social status and political power that white people had access to, policies that were either never changed or evolved to appear reformed yet have the same result. Without a proper understanding of that, Curry said, meaningful criminal justice reform is not possible.

Curry has doubts that this understanding is achievable with some of the people in power, particularly Huntsville Police Chief Mark McMurray.

“With his use of the term ‘Oriental’ and things of that nature, it is clear that he’s not in 2020 as it relates to diversity, equity and inclusion, so that’s concerning,” she said.

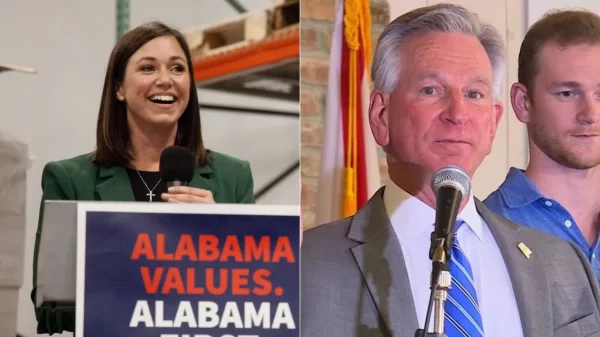

Neither does she have faith in Mayor Battle’s appetite for change. He was running for reelection in the months after protesters were injured and was often silent during public meetings as angry residents criticized the city council’s perceived apathy at their outrage. Battle was reelected by an overwhelming 78 percent of the vote on Aug. 25.

“He’s planning for whatever his future is, and he’s catering to a conservative base who is all about law and order and that kind of ‘comply and die’ mindset, without introducing an alternative,” Curry said.

In response to a list of 10 reforms that CCCJR asked for and more than a dozen others proposed by different groups, McMurray released a 73-page document outlining what his department has done and can do to address the issues raised.

“Huntsville police strive to maintain a culture of continuous improvement,” McMurray said in a statement. “We recognize this can only be accomplished through routine engagement with citizens and organizations concerned with the manner of law enforcement employed throughout the community. We welcome this opportunity to address concerns and suggestions and look forward to ongoing change and conversation.”

The release included a statement from Battle: “Huntsville police hold themselves to the highest law enforcement standards, and they hold themselves accountable to our community. This includes listening and working with residents, embracing and enacting progressive police procedures, and holding officers accountable for their actions. I am proud of this police department and their commitment to Huntsville.”

CCCJR released a response that criticized the report for lacking measurable steps and a timeline for implementation.

“The CCCJR repeats its request for a commencement of periodic small group conversations amongst citizens, law enforcement and other community stakeholders. The humanity and future of Huntsville is at stake. We will not stop until our streets are truly safe for everyone,” the release stated.

McMurray has not met with anyone from CCCJR. Neither has Battle. Many of its members participated in listening sessions held by the Huntsville Police Citizens Advisory Council, which is conducting a review of police actions on June 1 and 3. HPCAC member David Little said the review is ongoing with the help of its independent counsel, Birmingham attorneys Liz Huntley and Jack Sharman. He declined to comment on a timeline for completion.

An informed perspective

Charles Miller, a retired law enforcement officer who is advising CCCJR, holds a dim view of the situation. The general public thinks police exist to protect and serve the public, he said, but Huntsville’s police have demonstrated that they are there to protect and serve the city’s power structure.

“That’s another way to put why Tommy Battle picked McMurray, who is a dumb, head-breaking cop,” Miller said. “That’s what he is. He’ll never be any more than that.”

Miller moved to Huntsville 16 years ago from Florida, where he worked for the Florida Department of Law Enforcement, an investigative agency. His primary role was to come up with ways to track officer certification and decertification, which included sitting in on decertification hearings. That provided him a lot of insight into officer misconduct, he said.

Curry said Miller has been especially useful in helping CCCJR’s leaders understand how police departments work and what reasoning they use to make their decisions.

Miller said that his experience taught him what things make a police department work well or not work well. The best policing is apolitical, he said. Good commanders shouldn’t appear to support any political party or ideology beyond public safety. Many police forces around the country have regressed into displays of political allegiance, Miller said, and based on McMurray’s public comments, that includes Huntsville’s.

In his after-action report to the Huntsville City Council, McMurray said that social media posts indicated that antifa sympathizers sought to turn the peaceful protests violent, necessitating the widespread use of tear gas and kinetic impact rounds by at least two of the agencies under his command on June 3.

A member of the antifa network in Alabama told APR that none of its members participated in Huntsville’s protests.

Miller said McMurray’s claims constituted the sort of partisanship that erodes the department’s role as a public service.

“To put it indelicately, he’s a Republican bootlicker, and that’s why he got appointed,” Miller said. “My wife could tell you, the day that was announced in the news, I had to be pulled off the ceiling. He was the worst guy, the worst commander, to be put in that position. They passed over a couple of really good captains that would have been much better — would have been much less political. But that’s what our mayor wants and that’s what he got, and that’s what we’re living with.”

Battle appointed McMurray in 2015. The mayor has backed the chief through several serious use-of-force controversies, including the killing of a suicidal man by officer William Darby in 2018. Darby was cleared by an internal department review, then indicted for murder by a grand jury. His trial is pending.

Responding to continued calls for McMurray to be replaced, Battle said last month that he has not lost confidence in the chief.

Miller said that as an officer, he always had “a distaste for the idea that police be used as a militia.” He called the militarization of police a disaster.

“It’s the kind of thing where if you have a tool, you’re gonna use it,” he said. “And being deployed with the heavy riot gear, the tear gas and all that, and being positioned right up next to the crowd, was a tactical mistake. Very cynically, I’m going to say whoever was in charge at the scene of that action was looking for a fight and they created one. That’s why I say it’s a police riot.”

Miller called the issue a political problem that will require a political solution. In his advisory role with CCCJR, he’s helping them focus on what is practical. He expects Battle to toe the Republican party line on policing but be a bit more moderate, willing to reevaluate public safety but unwilling to do any fundamental restructuring. Miller is advising that they must gain political leverage for any hope of long-term changes or to have leverage with powerful stakeholders like the police union. He is looking for viable candidates to run in future elections.

Political solutions

Curry has experience in grassroots organizing. She has worked in community outreach on issues like homelessness and on political campaigns. In 2008, she ran unsuccessfully for the District 5 seat on the city council, coming in third out of seven candidates.

Councilman Bill Kling offered her a seat on the HPCAC but she declined because members have to sign a confidentiality agreement. That contradicts the kind of transparency Curry and CCCJR have asked of police and the city council, she said.

Curry attributes Battle’s wide political support to the promotion of Huntsville’s image as an economically thriving city free of the backwardness that people in other regions associate with the Deep South. She was disappointed that more people didn’t turn out to vote against Battle. She said she thought that was because the protests happened too late in the election year to have more impact, and because CCCJR didn’t make a coordinated election effort.

Huntsville’s progressive image is false, Curry said, adding that the city is mostly segregated and leadership’s focus is economic development over everything else. The progressive tone is only meant to attract workers needed to fill jobs as the city expands, she said.

“Anybody that has moved here and become civically engaged, they quickly realize that that was just a puff of smoke that they were attracted to, and then the reality is this modern Jim Crow South kind of thing,” she said.

One such resident is Katie Lorenze, 33. She moved to Huntsville from Madison, Wisconsin, a year ago when her husband got a job there. She was initially terrified of moving to Alabama, she said, but was told that Huntsville is different. Then she saw videos of what police did on June 3, which “absolutely shattered the idea that I had of Huntsville.”

Lorenze balked at McMurray’s claim that police exercised patience and restraint by waiting 45 minutes after the protest’s permit expired to start shooting nonviolent protesters with tear gas and rubber bullets. Back in Madison, with its progressive and politically engaged population, protests are common and police are always present, she said. The idea that they’d use mass violence against protesters never seemed like a possibility there.

When she organized a small local Women’s March to coincide with the national event on Oct. 17, the police department and County Commissioner’s office seemed to present more hurdles than help, she said. All of it has been enough that she wants to see significant action taken by the city. She noted that to fill the sort of technology and engineering jobs that Huntsville is known for, companies have to recruit well-educated people from all over the country.

“People who tend to come from more progressive places,” Lorenze said. “And what, they expect them to leave their ideas at the door? No, that’s not going to happen. So there’s going to have to be some sort of shift here or folks like us who come from more mainstream and less radical right-wing ideology, we’re not going to stay.”

Curry and several members of CCCJR are working to create a public relations campaign to launch outside Huntsville to raise awareness about the gap they see between the city’s messaging and its reality. They want to avoid using inflammatory language, she said, but they want to bust what they see as a myth the city is using as a cover for regressive policies.

If their effort is successful, it will be a model that other communities can replicate, Curry said. She just doesn’t see it happening without a shift in the balance of power. Nor does she think the city’s powerful understand the determination of her coalition of people who love what their city was supposed to be. Their outrage has turned into resolve.

“Their eyes were opened to the fact that, oh, we are not Mayberry,” Curry said. “We have a militarized police force here who doesn’t mind doing what took place.”