Over the next few weeks, the Alabama Department of Environmental Management will hold public hearings on the regulated closures of three coal combustion residuals storage sites, commonly referred to as coal ash ponds.

While ADEM receives high marks from federal regulators and businesses within Alabama, there is always a certain skepticism that surrounds environmental issues both on the left and the right side of the political spectrum.

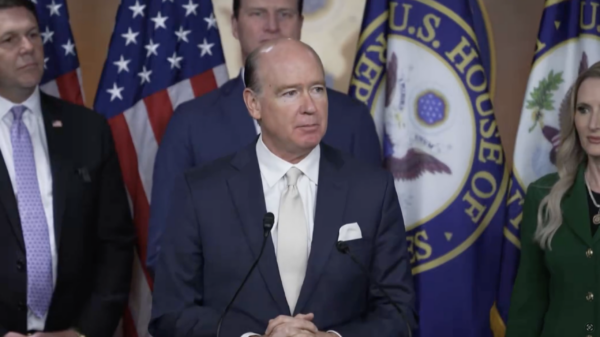

Recently, APR spoke with ADEM Director Lance LeFleur to understand the process and how the public could be assured that steps taken would lead to a safe and effective outcome.

“I know that there’s skepticism about government,” LeFleur said. “And it’s healthy to have skepticism about government, state governments, local government, federal government. Skepticism is part of how we operate.” But LeFleur wants the public to know that ADEM’s first purpose is Alabamians’ health and safety.

“Our mission is to ensure for all Alabamians a safe, healthful and productive environment,” LeFleur said. “It’s a mission that ADEM and its nearly 600 employees take very seriously.”

LeFleur says while there are many competing sides to the issues that arise from coal ash disposal, ADEM must focus on “science and the laws.”

According to LeFleur, there are two primary issues that must be addressed when closing coal ash ponds: “avoid threats of spills into waterways or onto land, and preventing and cleaning up groundwater contamination from arsenic, mercury, lead and other hazardous elements that may leach from the coal ash.”

EPA does not classify coal residue as hazardous waste, but LeFleur says that all closures must ensure dangerous elements are not leaching down into the groundwater.

“I think there’s pretty much unanimous opinion that these coal ash ponds need to be closed; they need to be closed properly,” said LeFleur. “And we need to clean up the groundwater that’s in place.”

He says that the entire process will take decades, but the power companies have committed to safely closing the coal ash ponds. “We are dealing with power companies that are going to be around for a long time. And they, they are obligated to get the result right,” said LeFleur.

Alabama currently has 14 regulated CCR units at eight sites throughout the state. They are comprised of 10 unlined surface impoundments, one lined landfill, one lined surface impoundment all closed, and two lined landfills still in operation.

Public hearings are a significant part of the permit granting process, according to LeFleur, and ADEM’s website allows any individual to review every document and comment about a coal ash pond’s closing.

“You can see all of the comments that we received,” LeFleur said. “Every issue raised during the comment period and written response to comments are available.” ADEM’s website also includes the closure plans as well as all correspondence between agency and utility companies.

According to ADEM, the purpose of these hearings is to allow the public, including nearby residents, environmental groups, and others, opportunities to weigh in on the proposed permits.

“This past summer, Alabama Power, TVA, and PowerSouth held informational meetings in the communities where their affected plants are located to explain their proposed groundwater cleanup plan —including the CCR unit closure component— and answer residents’ questions,” said LeFleur.

Closing a unit requires months of planning with ADEM engineers to make sure all procedures are followed correctly. Federal rules for closing CCRs have only been around since April 2015, when EPA released final measures for management and disposal of CCRs from electric utilities. In 2018, ADEM issued its state CCR rule, which closely tracks the federal regulations.

Under both Presidents Obama and Trump, the EPA has allowed for coal ash sites to be closed by two methods — closure in place and by removal.

Alabama’s utilities have chosen the cap in place method. Some environmental groups prefer removal. But estimates say that moving CCRs from Alabama Power’s Plant Barry would take around 30 years with trucks leaving the site every six minutes.

“Regardless of which method of closure is used, that process will take a couple of years to accomplish at these sites,” said LeFleur. “If it’s kept in place, the material has been de-watered then pushed together to create a smaller footprint, and then that will be covered with an impervious cover.”

The objective, according to ADEM, is to protect the groundwater and the environment from pollution.

Power providers and environmentalists seem to agree there isn’t a perfect solution. Public hearings are to ensure that community voices and those of environmentalists are heard.

“This entire process is designed to stop contamination to groundwater and future contamination to groundwater; those are the most important facts now,” said LeFleur. “There are always political issues, you know, at least two sides, and sometimes there’s three, four or five sides. We focus on science and the laws. That’s what we do.”

While ADEM has its critics, it receives a high rating from the EPA, and an annual survey by the Alabama Department of Commerce finds that it gets top marks from business and industry in the state.

ADEM’s first public hearing on coal ash permits will be held Tuesday, Oct. 20, for Alabama Power’s Miller Steam Plant in west Jefferson County. The meeting will be at 6 p.m. at the West Jefferson Town Hall. Other upcoming hearings are Thursday, Oct. 22, for Plant Greene County located in Greene County and Oct. 29 for Plant Gadsden in Etowah County.