About two dozen people tuned in to a webinar last Tuesday called “How to Spot Fake News and Content” hosted by Terry Lathan, chair of the Alabama Republican Party. Lathan said the title made a journalist friend of hers nervous when she told him about it.

“I think he thought it was an opportunity for me to yell about ‘fake news’ and ‘everything’s a lie’ and to slam journalists, and that’s not what I’m doing at all,” she said.

The hour-long presentation she gave was closer to a standard Media Literacy 101 course that students majoring in journalism or communications might take at any college or university.

Lathan, a former fifth grade teacher, explained some basic steps for decoding articles and websites online that purport to present accurate information. Be careful not to mistake websites that mimic the names, logos and appearances of established news outlets for the real thing, she said.

She gave the example of a site that looks like ABC News but is discernible by the “.co” at the end of the URL, a common feature of sites mimicking news agencies. A bit of searching revealed that this one was owned by Paul Horner of the Westboro Baptist Church, known for its anti-LGBTQ campaigns and protests at military funerals. One of its fake stories had the headline, “President Obama signed an executive order banning assault weapon sales.”

Lathan told her viewers to be cautious about being taken in by stories that trigger strong emotional responses, particularly when the information is something they want to be true. Every person’s online activity creates a digital footprint that companies have turned into a science of behavior prediction, she said. Their business models are built around it.

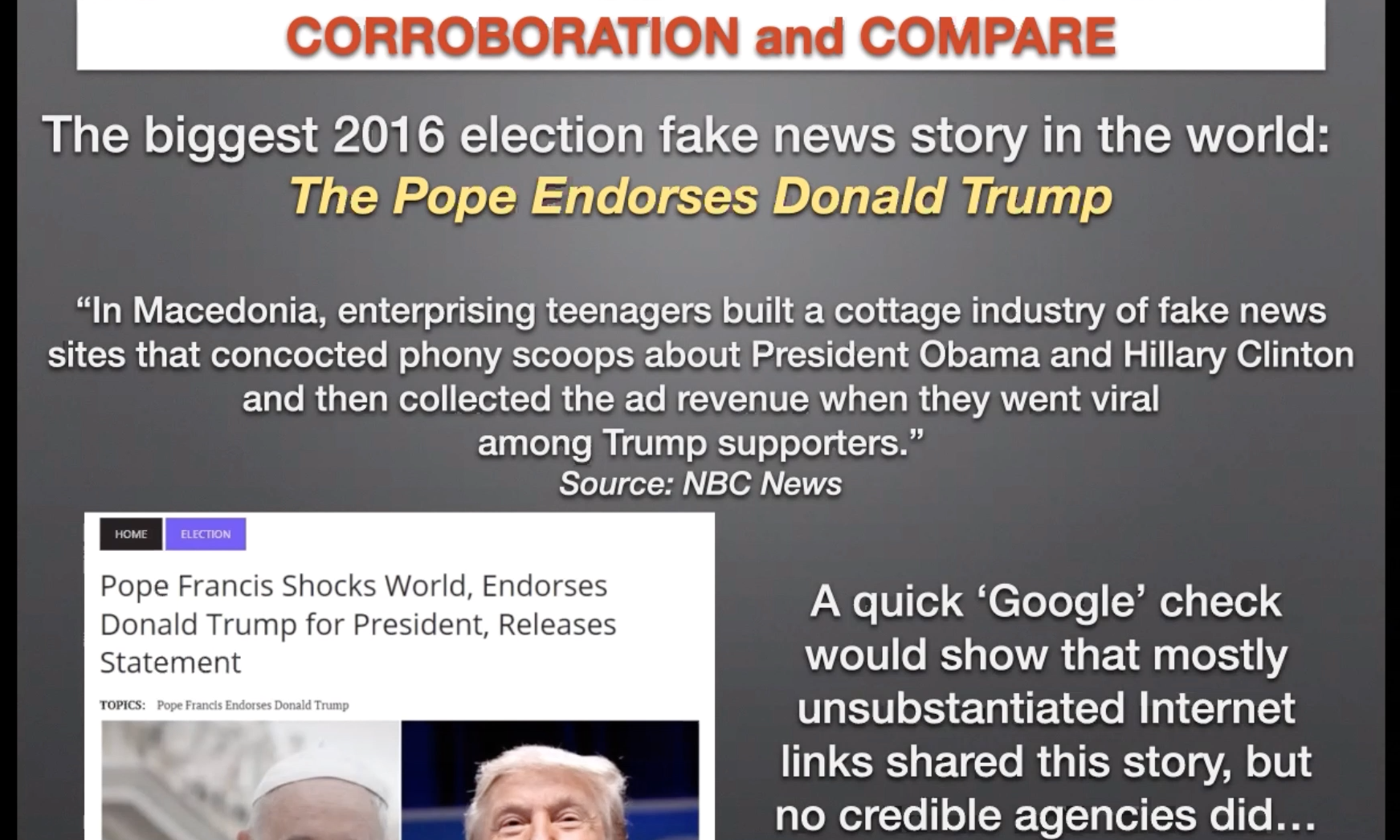

Corroboration is key, Lathan said. She showed an article posted by the Facebook page “American News.” Those are two words she likes, Lathan said, next to a thumbnail photo of the page’s profile image, a portrait of Ronald Reagan in front of an American flag. More of what she likes. Then the headline: “Denzel Washington backs Trump in the most epic way possible,” under a photo of Washington in front of an American flag.

“Now the reality is we read those words, we go, ‘What!? Oh my gosh!’ Just that instinct, just kneejerk emotional,” Lathan said.

Her next step was a quick internet search for “Denzel Washington Trump.” It returned no similar news stories.

“You think Rush Limbaugh wouldn’t have been talking about this?” she asked. “Because I’m pretty sure he would have been if it were true.”

Lathan said she did not use any existing resources about navigating media and misinformation online to create her presentation. She based it on her own experiences falling prey to deceptive content, and on seeing how common it is among her online network. When a friend shares something questionable, she’ll sometimes alert them via private message to avoid making them feel embarrassed or defensive.

Lathan said she wanted to share some tools that people can use as the general election approaches.

“I think it’s important that because we disagree with something doesn’t mean that it’s fake, and on the other hand, we need the whole story told and not just pieces pulled out and told. That happens very often in media,” Lathan said.

Another strategy she recommended was being skeptical of stories that quote unnamed sources or present information that is unconfirmed — practices that are fairly common at reputable news outlets under certain circumstances. They are also subjects of ongoing debate within journalism circles.

Lathan used the example of a Sept. 3 article in The Atlantic, which reported that Trump skipped a visit to an American military cemetery in Paris, saying, “Why should I go to that cemetery? It’s filled with losers.” The story quoted “four people with firsthand knowledge of the discussion that day.” It contained several other allegations of disparaging comments, all related by anonymous sources.

Reporters frequently weigh their access to inside information from people they’ve developed relationships with against their professional obligation — and career ambitions — to report things that the public should know, or juicy items that will drive website traffic. Much of that balancing act falls within a gray area. Betraying journalistic standards of accuracy, a source’s expectation of anonymity or the public’s right to know can each carry heavy consequences for all parties.

Arguments on both sides of the debate have been published by the Poynter Institute, a nonprofit journalism ethics and teaching organization founded in 1975. In a 2014 post of a lecture by John Christie of the Maine Center for Public Interest Reporting, Christie warned that “the frequent and often unnecessary use of anonymous sources reinforces the mistrust readers already have for journalists.”

In a Sept. 8 post about the Atlantic story, Poynter’s senior media writer, Tom Jones, wrote that the information’s value outweighed the doubt its sourcing feeds in the minds of many.

Lathan mentioned Poynter in her webinar as she analyzed the fact-checking website PolitiFact, which Poynter owns. It appeared reasonably legitimate, she said, until she looked at how it is funded. On its list of donors, the largest in 2020 so far is Democracy Fund.

“I clicked on Democracy Fund because they donated $75,000 and it does not exist,” Lathan said. “It’s a dead link. And it just took me, I mean really, a few seconds to see all this and go, ‘Huh, probably not a reputable place I want to go to, I want to buy anything from.’”

Democracy Fund is a charitable organization established by Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay. Billing itself as nonpartisan and independent, it has donated more than $150 million since 2014 to organizations working to strengthen democratic institutions out of a commitment to “ensuring that people with differing perspectives debate and fairly determine the priorities of the country, while protecting the dignity and equal rights of every individual.”

Lathan’s determination that the dead link on PolitiFact meant that Democracy Fund wasn’t real indicated what was missing from the presentation, according to Chris Roberts, a professor at the University of Alabama’s Department of Journalism and Creative Media who specializes in journalism ethics and political communication. He’s also a former Birmingham News reporter who has led workshops on media literacy.

After viewing the presentation, Roberts said that it lacked any suggestion that a person should look outside their media bubble to be exposed to different points of view.

“She talked about media literacy while following party lines – CNN ratings are down, information may be suspect if Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity aren’t talking about it, and anonymous sources are not to be trusted,” he said.

While Lathan’s advice generally aligns with best practices for discerning news consumers, Roberts said that the tendency to consume news in a media ecosystem that reflects one’s existing belief system can hobble a person’s ability to recognize real news from false news.

“That may be why Mrs. Lathan did not recognize PolitiFact as a Pulitzer-winning site that separates fact from falsehood communicated by politicians across the political spectrum, and a site that teaches media literacy,” Roberts said. “While PolitiFact might need to do a better job of distinguishing ads from its editorial content, Mrs. Latham incorrectly thought an ad link to a Vogue story about first lady Melania Trump was PolitiFact content. And it may be why she said she only needed a few seconds to decide that the Democracy Fund does not exist, when a few seconds more might have taken her to the organization’s site.”

On the whole, Roberts said he thought Lathan’s effort was well-intentioned and useful, and important considering that she’s a top official in the state’s Republican Party. He cited research that shows that people who identify as politically conservative are more likely than others to share factually incorrect information on social media.

Lathan has no illusions about how often information is manipulated for political gain by those she shares the political realm with, regardless of party affiliation. The HBO documentary After Truth examines a misinformation campaign waged on behalf of Sen. Doug Jones in 2018, which Jones denounces in the film.

Lathan said she’d rather lose an election than win it with deceit. “I’m a person that believes if you go to church on Sunday and you believe those words in the book on Sunday, and you live your life through that book — with a lot of imperfection and mistakes — that that should be Monday through Saturday as well,” Lathan said.

It was in that spirit that she decided to do the webinar.

“There is a life after politics,” she said. “There is a life after an election. There’s life after being a public official, and I believe in integrity. If it’s false, it’s wrong.”