The problems that plague Alabama’s Black Belt are widely known, but there’s no single definition of what constitutes the Black Belt, and without one, that makes it difficult to find long-term solutions to those problems, according to a report released Tuesday.

The University of Alabama’s Education Policy Center set out to define exactly which counties should be included in the definition of the Black Belt. Traditionally, the region is defined as areas of South-Central Alabama where slaves once tended cotton fields and where today many small Black communities are hard-hit by an exodus of their youth and economic and educational realities not shared by their wealthier, whiter neighboring communities.

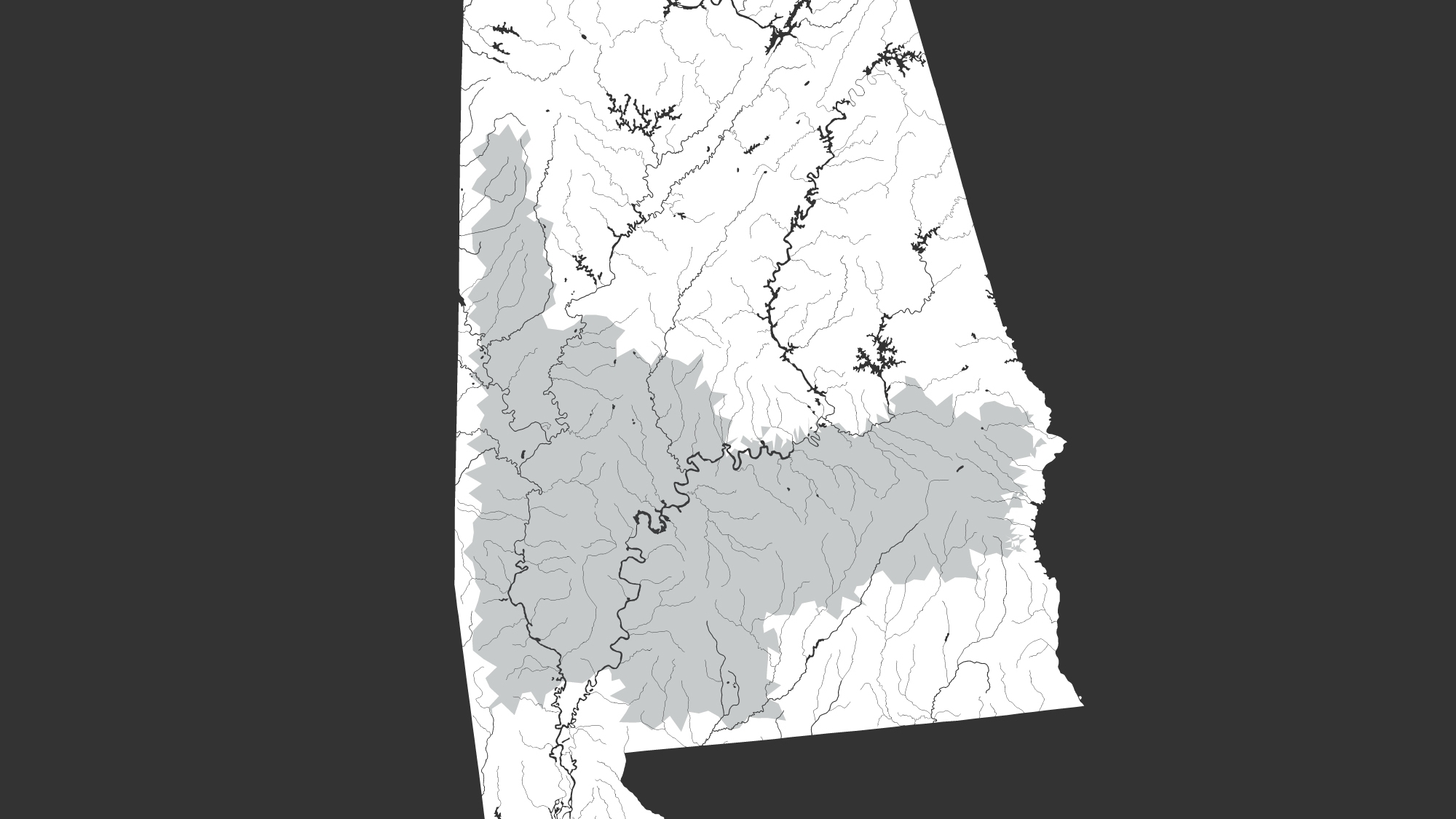

The center’s report, entitled “Defining Alabama’s Black Belt Region,” used a broader definition of the area that includes 24 counties but notes that some — including Crenshaw, Pike, Montgomery and Russell counties — haven’t suffered as badly as others.

Numerous other state and federal entities define the Black Belt as comprising between 12 and 23 Alabama counties.

{{CODE1}}

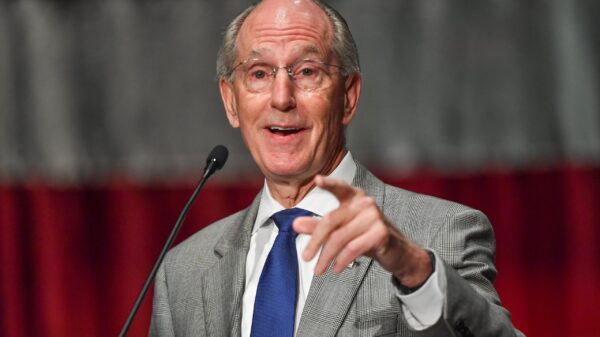

Stephen Katsinas, director of the university’s Education Policy Center and one of the authors of the report, told reporters during an online briefing Monday that they decided to use a more inclusive definition because there was no reason to exclude any county.

Katsinas said the decision to come to an agreed-upon definition of the Black Belt is an important policy discussion to have because you can’t “improve what you can’t measure, and we can’t measure it right now.”

Wayne Flynt, professor emeritus of history at Auburn University and a pre-eminent historian of Alabama and the South, told reporters Monday that there is both a historical and geological definition of the Black Belt, where the vast sea that once covered the land receded, leaving behind chalk formations in the earth, which is partly responsible for the rich soil to which cotton and other crops take easily.

But the Black Belt didn’t get its name due to the black soil, Flint said, but rather because of the people who worked those fields and lived on the land: Black slaves who gave way to Black sharecroppers in the years after the Civil War.

“If you use a geological definition of the Black Belt, you get one thing,” Flint said. “If you use a historical one, you get another, and as you get attitudes toward race, it varies with time and history, and so it’s a lot more complicated.”

Art Dunning, former vice chancellor of the UA System and a native of Marengo County, considered by all entities as a Black Belt county, told reporters during Monday’s briefing that his memory of the Black Belt is around the issues of politics, economics and social structures.

“And it’s through the eyes of coming of age on those issues as a teenager,” Dunning said.

Dunning said during the 1950s, when he traveled to Selma to shop at the age of 14 or 15, Black people could not stand on the streets but had to wait in two places: a grocery store parking lot or a Black-only waiting room at the Greyhound bus station.

His father was a high school principal and his mother a teacher, but Dunning said he had friends whose families were sharecroppers, and he got an up-close glimpse as to what was causing the migration of Black people out of the Black Belt.

“One was the dehumanization and stigma that was tied to the politics, history and culture of the region,” Dunning said. “The other was terror and violence. And lastly, the belief that there’s inherent superiority and inherent inferiority.”

“All of those structures are tied around those things, and people who like me, could not wait to get out of those under-resourced high schools, poor facilities, poor supplies to go to Southside Chicago, to go to Philadelphia, to New York, to Oakland and to San Francisco,” Dunning said.

Katsinas said the fact that there’s never been a concrete definition of the Black Belt says a lot about Alabama, and that in the center’s effort to define it, he could agree with varying aspects of what was discussed during Monday’s briefing.

“What I can’t go with is to do nothing,” Katsinas said. “I think there’s a cost of doing nothing, and that cost is the cost we should not accept paying for anymore.”

Tuesday’s report is the latest in the center’s series of reports on the Black Belt. To find others, visit the center here.