LaTosha Brown asked the same question of every speaker as they each took their turn during a virtual town hall on Facebook Live earlier this month.

“What do you see?” she asked throughout the event, held to give activists and residents in Selma a platform for their thoughts about changing the name of the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

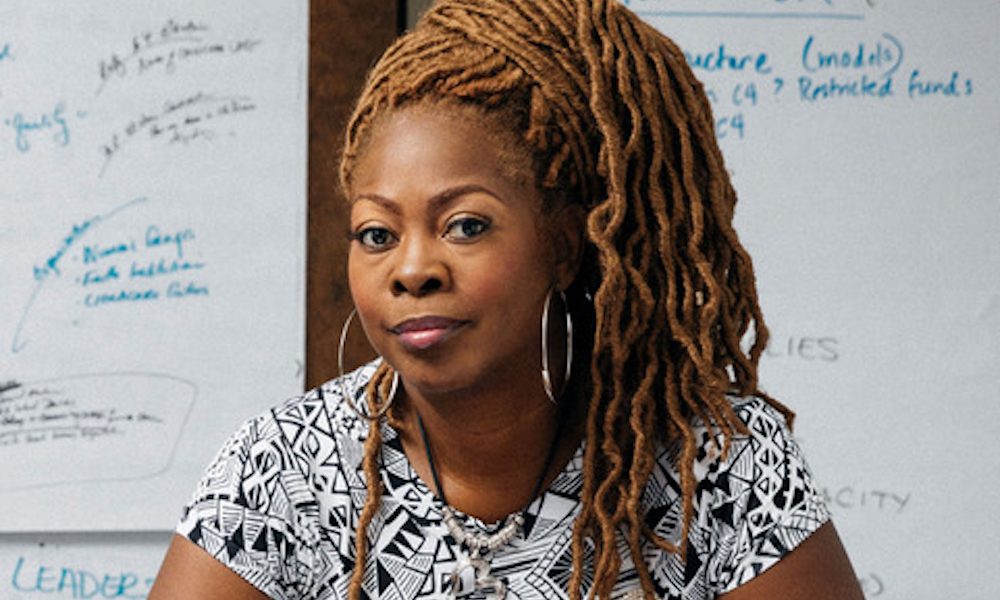

Brown, 49, grew up in Selma. Now based in Georgia, she’s a nationally recognized political organizer and educator, co-founder of Black Voters Matter and a fellow at Harvard University’s Institute of Politics. Her entreaty to other daughters and sons of Selma was open-ended, meant to center their individual visions for their struggling town and its famous landmark. Until then, the conversation about the bridge’s fate had been playing out on Twitter among people with no connection to the community that maintains its legacy.

That approach is at the heart of everything Brown does, she said. It was the reason that she and radio host and writer Cliff Albright created BVM. They felt that Black voters and the issues affecting them were being ignored, “treated like a footnote if mentioned at all,” Brown said.

Rather than parachuting into communities and organizing as they see fit — “We reject that model,” Brown said — BVM supports existing grassroots infrastructure in Black communities, particularly those outside of the urban centers that tend to be the focus of voting rights initiatives.

The organization does its work year-round, in and out of election season in the 11 states it operates in, nine of them in the Deep South. The work includes voter registration, advocating for policies that expand voting rights and access, resisting voter ID laws, re-entry restoration of rights and strengthening the Voting Rights Act.

BVM also develops organizational infrastructure where little or none exists, including training local staff and developing candidates and a general network, and sometimes funding activities related to specific elections.

One such election is what BVM is most known for — Democratic Sen. Doug Jones’s 2017 defeat of Republican candidate Roy Moore. BVM’s role in the upset demonstrates a reality that Brown said transcends party affiliation and is being debated regarding Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden’s campaign.

“In many ways, Black people have been reduced down to participation,” she said. “And we see Black people as having the potential for having power.”

Jones’s messaging seemed geared toward a white audience — one campaign ad featured a Union and a Confederate soldier and Jones saying he wanted compromise — so BVM and its partner organizations focused on voters and what was good for them.

The strategy shifts attention from a candidate and their personal weaknesses and strengths to voters and what is best for them, Brown said. They reminded Black voters that they had agency in state politics and weren’t simply voting to give someone else power.

After Jones won, BVM kept up its efforts and organized an open letter to Jones. One of their stated expectations was that he hire Black staffers. He hired Dana Gresham, making Jones the only Senate Democrat to have a Black chief of staff. BVM lobbied on issues like water and broadband access, using the political victory to steer attention and resources to rural communities that had gone underserved.

“We did not see the election as an end-all-be-all, but just one step along the way that we could use to build power,” Brown said.

She’s worried about voter suppression this election, which Brown said is a problem that goes deeper than Republican versus Democrat or white versus Black. She learned this, she said, when she ran for the state Board of Education in 1998. After a close race, she received a call from the state Democratic Party minutes after the election was certified in favor of the incumbent she opposed. Eight-hundred ballots had been found, she said she was told, in a safe belonging to the sheriff of Wilcox County, where she had many supporters. The sheriff had forgotten about them and it was too late for them to be counted, she said.

Her opponent was a Black man and a Democrat, yet Black votes were suppressed to protect the establishment, Brown claims.

That’s not extraordinary in Alabama, she said. It is with that expectation that BVM is increasing its activities with an influx of funding and the help of celebrities. The organization recently received $500,000 from the Southern Poverty Law Center and the Community Foundation for Greater Atlanta to split between its efforts in Alabama and Georgia. It received the same amount from Michael Jordan last month, and has been promoted by Ariana Grande, Justin Bieber and Dennis Rodman.

The support is reflective of the work BVM has done, Brown said, but is also reflective of this political moment.

“I think people have a heightened understanding of the importance and the value of the Black vote, and protecting and advancing democracy,” she said.

In each state that it operates, BVM has between 20 and 25 partner organizations. Alabama is on the higher end because the organization has been there longest. After working all over the country, Brown said that her home state has some of the best grassroots organizing she has ever seen.

“What gives me hope is that in the midst of a state that is rife with structural racism, that is in my opinion on the wrong side of history on anything that is related to justice, that somehow — in the midst of that — the people still rise up,” she said.

She noted that it is primarily Black women at the forefront of these movements. And just as dirty political trickery crosses race and party lines, Brown said, so do the benefits of these movements’ achievements. In a state that consistently ranks among the lowest in the country for public health and education, Brown said that many of those who vote against what she’s fighting for stand to gain from the victories of her and her colleagues.

“To the extent that that state is going to change, Black women are going to transform that state. It is unquestionable,” she said. “We’re going to have to save that state from itself.”